Being a journalist in – or reporting on – the Middle East brings with it many challenges.

One key issue, for journalists and news consumers alike, is the relative lack of media freedom, and freedom of expression, in the region.

This can drive conversation into more controlled environments, like closed WhatsApp groups and encrypted apps like Telegram. It also results in self-censorship, due to privacy concerns and concern over what it is safe to say in the public domain. The fact that social networks are often banned or blocked in times of upheaval adds to this online wariness.

Yet at the same time, as our new report “State of Social Media, Middle East: 2018” demonstrates, the growth of social media use in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) continues unabated.

What should journalists make of this complicated landscape? Here are three considerations:

1. Be aware of the environment

As recently noted by the Brookings Institution’s Center based in Doha, Qatar: “The question of media freedom takes on a particular character in the Middle East. Worldwide, the Middle East is the most dangerous region for journalists. Not only journalists, but also media outlets themselves are now under existential threat.”

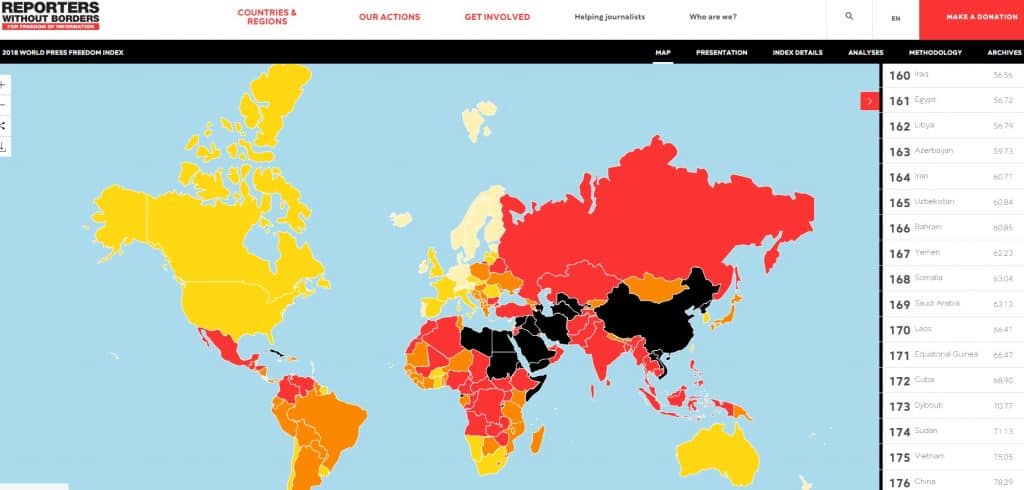

Reporters Without Borders highlighted this in their 2018 World Press Freedom Index, ranking a number of Middle Eastern countries near the bottom of their list.

The deaths and detainment of journalists in countries such as Syria and Yemen is a cause for concern, as is increased hostility towards journalists in Egypt.

In 2018, the Egyptian government passed legislation restricting where journalists can operate and making it obligatory for new media websites to apply for licenses. It also categorised social media accounts with more than 5,000 followers as media outlets, exposing them to monitoring by the authorities.

Even veteran journalists have been feeling the heat in Egypt. The New York Times correspondent and former Cairo bureau chief, David D. Kirkpatrick, was recently detained by security officials and expelled from the country with no explanation.

2018 World Press Freedom Index: Countries with the lowest rankings (many of them in the Middle East) are in black

Source: Reporters Without Borders

2. Opportunities for social media as a source

Despite this repressive backdrop and the self-censorship often resorted to by internet and social media users, social networks remain an avenue for stories and sources.

The potential for this was famously demonstrated by NPR’s Andy Carvin during the Arab Spring. More recently, regional outlets such as Al Jazeera have harnessed social media as a news source by reporting on the #BringDevBack movement started by Yemeni people looking to rebuild their country.

As with any source, content found on social networks needs to be treated with caution. This is particularly important given the increasing weaponisation of cyberspace (a trait not unique to the MENA region) to push political agendas.

Following the disappearance and murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, an investigation by NBC showed how Twitter accounts – belonging to both real people and bots – were promoting the denials of the Saudi Arabian government.

On the other hand, analysis by Reuters revealed a network of at least 53 websites which, “posing as authentic Arabic-language news outlets, have spread false information about the Saudi government and Khashoggi’s murder.” These stories were also amplified by automated Twitter bots.

This trend can also be seen in the online conversation about neighbouring Qatar. In May 2018, 29% of tweets in Arabic about Qatar – a nation at odds with several of its Gulf neighbours – were tweeted by bots. This is up from 17% a year before.

3. Social media as a platform for distribution and engagement

Although journalists need to be aware of this wider context, it shouldn’t deter them from using social media. Social networks are not just important channels for sources, they are also essential platforms for the distribution of content and engagement with audiences.

The growth of Facebook, for example, is one such opportunity. By early 2018 there were 164 million active monthly Facebook users in the Arab world, up from 56 million Facebook users just five years earlier.

Nearly half of young Arabs (49%) say they get their news on Facebook daily, up from 35% in 2017, and almost two thirds (63%) of Arab youth now say they look first to Facebook and Twitter for news.

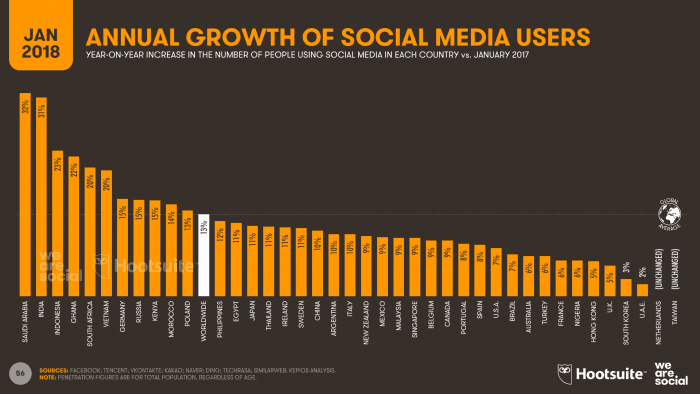

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia not only has the highest annual growth rate of social media users anywhere in the world (up 32% vs. a worldwide average of 13% between Jan 2017-Jan 2018), but a third of the country’s population uses Snapchat every day.

No wonder the ephemeral network is partnering with a range of local content providers, who are re-imagining their material for the platform.

Social media in the Middle East is a complex and fast-moving space. Keeping abreast of how this landscape is evolving is therefore essential for journalists if they are to understand, and harness, the full potential of social media in the region.

To find out more, download the full study, “State of Social Media, Middle East: 2018” by Damian Radcliffe and Payton Bruni, from the University of Oregon Scholars’ Bank, or view it online via Scribd, SlideShare, ResearchGate and Academia.Edu.

Main image: “Jamal Khashoggi (Trending Twitter Topics from 08.02.2019)” by trendingtopics is licensed under CC BY 2.0 | Image: Flickr

You might also be interested in The Arab World Is Changing And So Is Its Media Use.

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Tags: #BringDevBack, Arab Spring, Egypt, encrypted apps, Facebook, Jamal Khashoggi, Media Freedom, Reporters without Borders, self-censorship, Snapchat, Social media, Syria, Twitter, World Press Freedom Index, Yemen