In a previous piece for EJO, Jan Rau and Felix Simon examined the role played by digital counterpublics in today’s world. They now look at the case of Germany’s Identitarian movement and how it has sought to impose itself on the news agenda.

The established media still – for now – largely control the news agenda. They play the role of gatekeepers, determining what is discussed in the public arena. But the Internet is increasingly giving those who might once have been denied access to the media the chance to make their voices heard.

This has led to the birth of digital counterpublics, which were originally defined as alternative discussion spaces for marginalised social groups but have increasingly come to mean platforms for the development and dissemination of non-mainstream or at times even extremist viewpoints.

Such digital counterpublics are proving to be ever more adept at bypassing the traditional gatekeepers – the mainstream media – and ensuring that alternative views become part of the public agenda.

The Twin Dangers of Amplification and Normalisation

The increased prominence of such views in the public sphere puts the traditional media in a quandary. The two biggest dangers the media need to be aware of are amplification and normalisation. The mainstream media have to decide if reporting on a topic actually has the effect of exaggerating its importance. Media attention can make problematic stories, groups and individuals – who may be provocateurs and manipulators – appear bigger than they really are.

By giving giving a platform to undemocratic ideologies, the media also risk becoming complicit in the normalisation of such views. This shifting of the boundaries of the acceptable is sometimes referred to as the “Overton window”. Finally, the media also run the risk of legitimising false comparisons: clearly, Holocaust denial is not an equal perspective to the historical fact of the Holocaust.

Denying Extremists The Oxygen Of Publicity

Journalists often have to navigate their way through an ethical minefield. When should they report? Can “doing their job” actually cause harm? Are there occasions on which it would be better not to give extremist movements the publicity they crave?

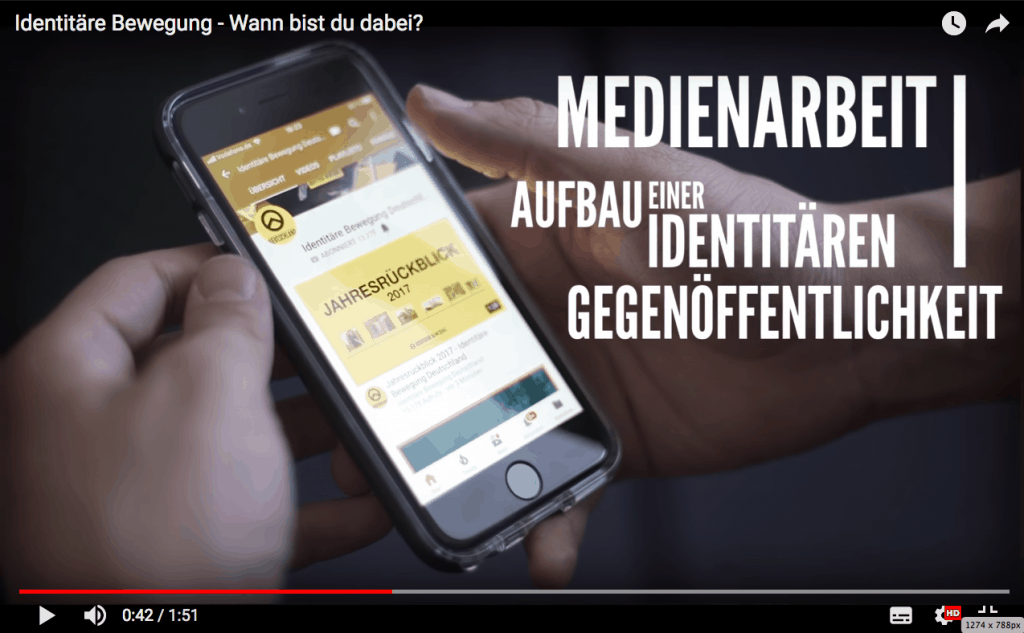

A still from an advert produced by the Identitarian Movement. The main text reads: “Media work: Creating an Identitarian counterpublic.” © Screenshot/YouTube Identitäre Bewegung Deutschland

A recent example of this occurred in Germany earlier this year, when supporters of the far-right Identitarian movement hung up posters outside various media premises throughout the country. The group claimed that the aim of its poster campaign was to draw attention to what it said was the media’s failure to report on left-wing violence in the country. The event was documented on YouTube, Twitter and the group’s website – the home of the digital counterpublic the Identitarian movement has been able to create. It was a bid for public attention and the strategy worked.

The German press went into full-blown outrage mode, labelling the poster campaign an attack on journalism and press freedom – a claim that seemed somewhat overstated. The extensive coverage of the propaganda campaign by the media made it a success. The original poster campaign may have been offline but was able to go viral thanks to the material spread by right-wing digital counterpublics and voluntarily amplified by the media. Several media outlets used publicity materials generated by the Identitarians (videos, photos and tweets) to illustrate their reports.

YouTube page of leading Identitarian figure Martin Sellner. The text reads “Welcome to the information war.” © Screenshot/YouTube Martin Sellner

The Identitarians freely acknowledge the purpose of their actions. They refer openly to such stunts as “media work”, saying that the aim is to influence public perception. The public face of the movement, the Austrian Martin Sellner, does not mince his words: on his YouTube page, he calls the campaign an “information war”.

One cannot help but think that the tone of the coverage of the Identitarians’ poster campaign by the mainstream media was an over-reaction that played into the hands of the extremists.

Challenges For Modern Journalism

The Internet and social media offer new opportunities to exploit the media’s liking for controversial topics. It allows political activists to initiate attention-grabbing campaigns and to influence the media agenda via digital counterpublics. Right-wing movements have shown themselves to be especially adept at exploiting this opportunity, though a few left-wing groups have also taken advantage of it. A 2018 report suggested that the German media have made some progress in learning how not to react to far-right “provocation”. Despite this, the response to the Identitarian movement’s “attacks” shows that there is still room for improvement.

It is important for media organisations to devise strategies for dealing with similar incidents in the future. The line between refusing to fall for agenda-setting attempts by extremist groups and shutting down legitimate oppositional voices is a fine one, and while in the case of the Identitarian Movement (clearly classified as right-wing extremist and monitored by Germany’s domestic intelligence service) this might be easy to decide, other cases might be much more difficult. Nevertheless, media outlets must become more aware of their own blind spots in order to tread this line with confidence.

The ability to meet these challenges requires an acute awareness of the tensions under which modern journalism operates and a willingness to face them head on.

Recommended Reading

- Whitney Phillips: The Oxygen of Amplification

- Rebecca Lewis & Alice Marwick: Media Manipulation

- Felix M. Simon: Strategic Silence Against Extremists

- Bernd Gäbler: AfD und Medien (in German)

- Denise-Marie Orday/Claes H. de Vreese: Covering Populist Leaders

Opinions expressed here are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO.

You might also be interested in The Power of Platforms.

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Tags: Agenda-Setting, amplification, Digital Counterpublics, Digital Media, Holocaust denial, Identitarian movement, Internet, Media Manipulation, normalisation, Overton window, Political Communication, public sphere, Social media, technological determinism