Mexico City – November 26, 2022: Female journalist covering a feminist march against gender violence. Shutterstock image.

“The truth is that I have cried many times. I have felt depressed because of what I cover and questioned if there is any use in me being there?” This is what Alexa Herrera, a photojournalist for the independent Mexican outlet La Lista, told me during an interview. She was describing her experience of covering gender violence in a country where ten women are being murdered every day.

My interview with Herrera shows that the endemic gender-based violence in Mexico is not just devastating for the women directly affected but can also have a marked effect on the journalists who cover their traumatic stories.

The potential mental health impact of covering violence is a growing concern, with research infrastructures and organisations such as the Journalism Education and Trauma Research Group and the Trust for Trauma Journalism being established to understand and address the issue.

Threats and intimidation

In 2012, a study about the psychological effects that Mexican journalists could experience while covering crime and drug violence reported that a quarter of the respondents had stopped their news coverage due to threats and intimidation and showed symptoms related to post-traumatic stress disorders- similar to those experienced by war journalists.

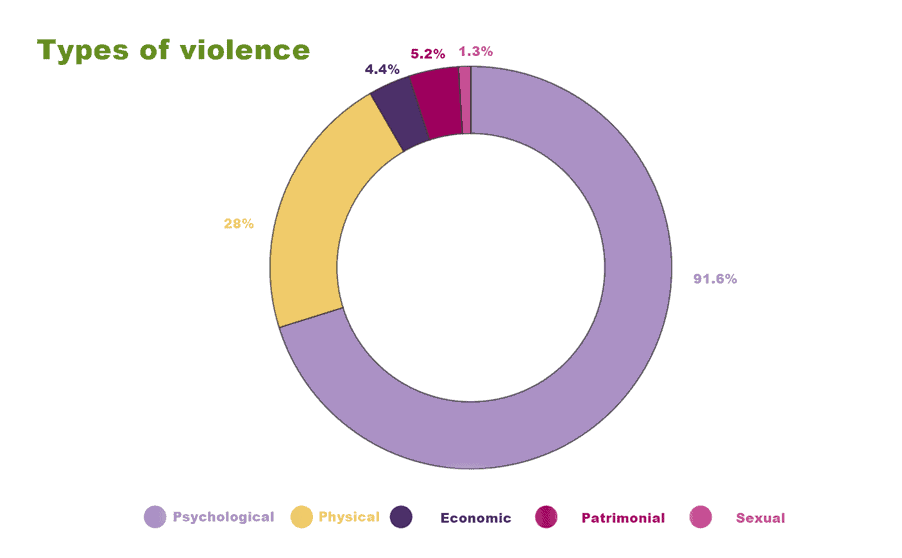

Communication and Information on Women (CIMAC), a Mexican organisation focused on journalism with a gender perspective, found in their 2021 report that of all the types of violence women journalists were subjected to, 91.6% was psychological. Additionally, their 2020 report stated that every 34 hours, a Mexican female journalist experiences some type of violence while conducting her journalistic duties.

Graph from CIMAC 2021 Annual Balance Report showing rates of violence in Mexico, including psychological, physical, economic, sexual, and patrimonial violence (the violation of a woman’s property rights).

Behind statistics, however, a large number of female reporters take to the streets every day to face the challenging realities of violence and trauma. María Ruiz, a photojournalist for the independent media Pie de Página, told me: “I think that after covering gender violence, I began to develop some awareness about the violence to which we are exposed, and about how to react to it. But with that came various fears. Another thing that this coverage has triggered in me is hopelessness. I am working on this in therapy because after covering many stories of violence without changing anything, it generated a sense of despair in my heart.”

Raising awareness

With the prevailing threat of unresolved femicides, this feeling of helplessness is common among female journalists. “It is like this impotent feeling and asking why am I there? (…) I covered a femicide in Nezahualcóyotl, (the case of) Andrea Salgado, and when I came back home, I felt very sad. I think I have become bitter, and I feel I do not tolerate many things anymore. It has really affected me. (…) We witness many things, we hear many things, and sometimes we can’t share everything because there is this barrier of us being journalists and not being able to get involved.”

Abeer Saady, a war correspondent and journalist safety trainer, stressed the importance of being aware of the potential psychosocial impact of covering violence and doing risk assessments before taking on an assignment. She said: “Awareness is key. Educate yourself. And know how to prioritise yourself when you work. It’s not about the journalistic work you have done. I have worked for 32 years. I dealt at the beginning of those years when I was still very young, as if this was the most important thing in the world. But you know what? I got injuries inside myself as well, not only in my body.”

Saady, who introduces key aspects of physical, digital and psychosocial safety in her safety handbook for women journalists in hostile environments, published by the International Association of Women in Radio and Television and supported by UNESCO, further explained the importance of support networks, especially at work. “The duty of colleagues is to support each other. I start with myself. I support my other colleagues.”

Organisational and structural change

In addition to individual care, counselling, and colleague support, Abeer also highlights the need for organisational and structural changes. “You should have rules,” she said. “Never to be tolerant of any kind of harassment. That’s important, and to have an open-door policy. Because the problem is sometimes you feel threatened to the extent that you might lose your job.”

The important takeaway is that women journalists must remember that their biggest priority should always be their well-being. However, the media industry must also be accountable for facilitating access to therapy, protecting women in workspaces and encouraging them to build support networks.

As far from reality as these goals may seem, the only way to promote change is by bringing these issues to light and supporting resilient women journalists who advocate for better work conditions for themselves and their peers.

“Student Perspective” is an EJO series featuring journalism students’ work. It aims to give students a platform to raise their profile and contribute to discussions on trends and other key issues in the media industry.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO or the organisations with which they are affiliated.

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in: Interview: Why young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina feel they are bearing the brunt of past conflicts

Tags: Covering Trauma, Covering violence in Mexico, violence against the media, Women in Journalism