Donald Trump, the Austrian FPÖ, the German AfD and Brexit: In many Western democracies right-wing, national and reactionary forces seem to be on the advance. The culprit for these developments is usually quickly identified – it is, of course, the Internet.

In the past, especially leftist and liberal thinkers and movements saw the Internet as a catalyst for democracy and freedom. Today the majority opinion is exactly the opposite: worries about social bots, “fake news”, echo chambers and psychological microtargeting have replaced the dream of a networked public and the new political movements that were said to emerge.

What happened? Were the utopians of the first hour so wrong? While scepticism remains necessary with regard to the actual role of the Internet in the political events mentioned above (more on this later), it cannot be denied that the Internet has become a catalyst for political change. However, it is less progressive forces that are currently profiting most from it – not the proponents of peace and democracy. Right-wing movements, in particular, are the ones currently using the Internet as a political platform with seemingly unprecedented success.

Welcome to the Age of Digital Counterpublics

One of the first researchers to address this phenomenon from a theoretical perspective was social scientist Ralph Schroeder. Schroeder, who researches and teaches at the Oxford Internet Institute, understands the public sphere as an arena characterised by a limited attention space. This arena, in turn, is mostly dominated by a few major media players.

As gatekeepers for the public arena, they determine to a considerable extent what is being discussed and what is not. In other words: they set the agenda. At the same time, various political ideologies try to gain access to the arena. Their goal: to influence the agenda of the media and thus the public agenda.

Now here comes the catch: the public arena is essentially a zero-sum game due to the limited amount of attention available. Put simply, this means that only a few actors and political ideologies can exist (and be heard) in the public arena at the same time.

But what does Schroeder mean by counterpublics? Basically, the concept goes back to the left-wing thinker Nancy Fraser and was originally defined as an alternative discussion space for marginalised social groups such as workers, women, minorities, or people with migration experience. Schroeder transfers this concept from the political left to the political right and into the Internet age: according to him, digital media offer right-wing populist movements and parties an opportunity to create digital counterpublics. Through these counterpublics, it then becomes possible for them to circumvent the gatekeepers – traditional media – and thus ultimately enter the public arena.

A breeding ground for a counterpublic: The Facebook page of FPÖ-politician HC Strache.

Just one example of such digital counter-publics are the “alternative news sites” of the Swedish Democrats, or the respective counterparts in Austria and Germany. The Facebook pages of leading right-wing populist FPÖ politicians such as Heinz-Christian Strache can also be understood as a form of digital counter-public. In demarcation and opposition to the ideologies and ideas already represented in the public arena, these sites provide the breeding ground for discourses which run counter to those of the “mainstream”.

Given enough time, these discourses can spread and gain access to the public arena in the medium term. For one, alternative sites might develop such a wide reach that they themselves become gatekeepers of the arena (although this is rare). It is, however, also possible that traditional media start covering these sites – which ultimately helps the messages promoted on these sites to spread more widely.

Four Types Of Digital Counterpublics

One aspect we haven’t addressed so far is the question of how these counter-publics actually work. In essence, four strategies can be identified.

- First, the Internet can reduce dependence on traditional media by enabling political actors or parties to communicate directly with their (potential) supporters through social media or websites. For example, during the so-called refugee crisis of 2015, the German AfD was able to successfully reach and mobilise its supporters through Facebook, even outside of the mainstream media.

- Secondly, as a hybrid strategy, we should mention agenda setting, which is only partly based on digital media. Digital channels (e.g. the above-mentioned Facebook pages of the FPÖ) are used as a medium to compose and promote an “original” message. Afterwards, however, the creators hope that this message will be taken up by traditional media and thus find its way into the public arena and thus to a wider audience. It usually helps if the original message makes very strong or, by normal standards, outrageous claims.

- Third, right-wing movements can benefit from a right-wing media scene on the Internet that tries to establish itself as an alternative source of news (alternative news sites in Sweden and Austria such as “unzensiert.at” are a good example). Similar to the first two strategies, this approach benefits from the relatively low cost of publishing content on the web. Decentralised distribution channels help, too.

- Fourth, digital media can provide a space for political “bottom-up” movements that organise themselves without help from “from above” (that is, help from political parties or other actors). In principle, these are the very digital grassroots movements once described by the first Internet utopians.

We Cannot Blame The Internet For Everything

And yet, the success of these strategies always depends on the context. In Germany, for example, the Internet currently plays a much smaller role for news consumption than in the US, while public broadcasting plays a much more central role. This makes it much more difficult for digital counterpublics to emerge. Instead, reactionary and populist forces in Germany are even more dependent on hybrid strategies such as agenda setting. The picture in the US, as Yochai Benkler and colleagues have shown in some of their recent work, couldn’t be more different.

In addition, we should not make the mistake of overestimating the potential role of the Internet in major political events. It goes without saying that the Internet has some effect in shaping political outcomes but much more decisive are structural factors and long-term developments: fears of globalisation, inequality, xenophobia and racism or individualisation tendencies, to name just a few.

In all known examples of digital counterpublics, these could only be successful in interaction with these and other much more important factors that permeate Western societies. Without doubt, right-wing digital counterpublics have played a significant role in establishing Donald Trump or the AfD. The actual causes for the success of these actors, however, lie elsewhere. The strong focus of public discussion on the Internet as the root of all evil is not only another instance of superficial techno-determinism; it is also not supported by the current state of science.

You might also be interested in The Power of Platforms.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO.

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

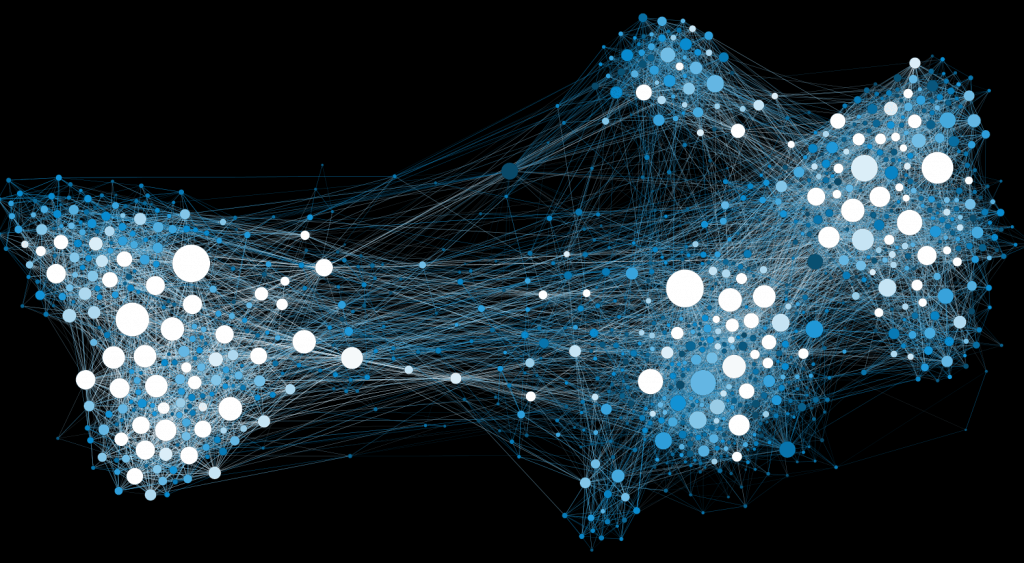

Head image: Martin Grandjean, CC BY 2.0

Have Digital Counterpublics Given Us Donald Trump, The AfD, And Brexit?

January 14, 2019 • Comment, Media and Politics, Recent • by Jan Rau and Felix Simon

Donald Trump, the Austrian FPÖ, the German AfD and Brexit: In many Western democracies right-wing, national and reactionary forces seem to be on the advance. The culprit for these developments is usually quickly identified – it is, of course, the Internet.

In the past, especially leftist and liberal thinkers and movements saw the Internet as a catalyst for democracy and freedom. Today the majority opinion is exactly the opposite: worries about social bots, “fake news”, echo chambers and psychological microtargeting have replaced the dream of a networked public and the new political movements that were said to emerge.

What happened? Were the utopians of the first hour so wrong? While scepticism remains necessary with regard to the actual role of the Internet in the political events mentioned above (more on this later), it cannot be denied that the Internet has become a catalyst for political change. However, it is less progressive forces that are currently profiting most from it – not the proponents of peace and democracy. Right-wing movements, in particular, are the ones currently using the Internet as a political platform with seemingly unprecedented success.

Welcome to the Age of Digital Counterpublics

One of the first researchers to address this phenomenon from a theoretical perspective was social scientist Ralph Schroeder. Schroeder, who researches and teaches at the Oxford Internet Institute, understands the public sphere as an arena characterised by a limited attention space. This arena, in turn, is mostly dominated by a few major media players.

As gatekeepers for the public arena, they determine to a considerable extent what is being discussed and what is not. In other words: they set the agenda. At the same time, various political ideologies try to gain access to the arena. Their goal: to influence the agenda of the media and thus the public agenda.

Now here comes the catch: the public arena is essentially a zero-sum game due to the limited amount of attention available. Put simply, this means that only a few actors and political ideologies can exist (and be heard) in the public arena at the same time.

But what does Schroeder mean by counterpublics? Basically, the concept goes back to the left-wing thinker Nancy Fraser and was originally defined as an alternative discussion space for marginalised social groups such as workers, women, minorities, or people with migration experience. Schroeder transfers this concept from the political left to the political right and into the Internet age: according to him, digital media offer right-wing populist movements and parties an opportunity to create digital counterpublics. Through these counterpublics, it then becomes possible for them to circumvent the gatekeepers – traditional media – and thus ultimately enter the public arena.

A breeding ground for a counterpublic: The Facebook page of FPÖ-politician HC Strache.

Just one example of such digital counter-publics are the “alternative news sites” of the Swedish Democrats, or the respective counterparts in Austria and Germany. The Facebook pages of leading right-wing populist FPÖ politicians such as Heinz-Christian Strache can also be understood as a form of digital counter-public. In demarcation and opposition to the ideologies and ideas already represented in the public arena, these sites provide the breeding ground for discourses which run counter to those of the “mainstream”.

Given enough time, these discourses can spread and gain access to the public arena in the medium term. For one, alternative sites might develop such a wide reach that they themselves become gatekeepers of the arena (although this is rare). It is, however, also possible that traditional media start covering these sites – which ultimately helps the messages promoted on these sites to spread more widely.

Four Types Of Digital Counterpublics

One aspect we haven’t addressed so far is the question of how these counter-publics actually work. In essence, four strategies can be identified.

We Cannot Blame The Internet For Everything

And yet, the success of these strategies always depends on the context. In Germany, for example, the Internet currently plays a much smaller role for news consumption than in the US, while public broadcasting plays a much more central role. This makes it much more difficult for digital counterpublics to emerge. Instead, reactionary and populist forces in Germany are even more dependent on hybrid strategies such as agenda setting. The picture in the US, as Yochai Benkler and colleagues have shown in some of their recent work, couldn’t be more different.

In addition, we should not make the mistake of overestimating the potential role of the Internet in major political events. It goes without saying that the Internet has some effect in shaping political outcomes but much more decisive are structural factors and long-term developments: fears of globalisation, inequality, xenophobia and racism or individualisation tendencies, to name just a few.

In all known examples of digital counterpublics, these could only be successful in interaction with these and other much more important factors that permeate Western societies. Without doubt, right-wing digital counterpublics have played a significant role in establishing Donald Trump or the AfD. The actual causes for the success of these actors, however, lie elsewhere. The strong focus of public discussion on the Internet as the root of all evil is not only another instance of superficial techno-determinism; it is also not supported by the current state of science.

You might also be interested in The Power of Platforms.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO.

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Head image: Martin Grandjean, CC BY 2.0

Tags: AfD, Agenda-Setting, bots, BREXIT, Digital Counterpublics, Digital Media, Internet, Political Communication, populism, Populists, public sphere, Social media, technological determinism, Trump

About the Author

Jan Rau and Felix Simon

Related Posts

What linking practices on Twitter tell us about...

Twitter’s design stokes hostility and controversy. Here’s why,...

Toxic Europeanisation – coverage of the 2019 EU...

The media revolution in Afghanistan

The new tool helping outlets measure the impact of investigative...

October 22, 2023

Audit of British Tory MP demonstrates the power of investigative...

September 13, 2023

The impact of competing tech regulations in the EU, US...

September 12, 2023

Enough ‘doomer’ news! How ‘solutions journalism’ can turn climate anxiety...

August 31, 2023

Student perspective: How Western media embraced TikTok to reach Gen...

August 19, 2023

Lessons from Spain: Why outlets need to unite to make...

July 26, 2023

INTERVIEW: Self-censorship and untold stories in Uganda

June 23, 2023

Student Perspective: Job insecurity at the root of poor mental...

June 9, 2023

The battle against disinformation and Russian propaganda in Central and...

June 1, 2023

Opinion: Why Poland’s rise on the Press Freedom Index is...

May 17, 2023

From ChatGPT to crime: how journalists are shaping the debate...

April 25, 2023

Student perspective: Supporting the journalists who face hopelessness, trauma and...

April 13, 2023

Interview: Why young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina feel they...

March 29, 2023

Humanitarian reporting: Why coverage of the Turkey and Syria earthquakes...

March 8, 2023

How women journalists in Burkina Faso are making a difference...

January 11, 2023

Dispelling the ‘green’ AI myth: the true environmental cost of...

December 29, 2022

New publication highlights the importance of the Black press in...

December 12, 2022

The enduring press freedom challenge: how Japan’s exclusive press clubs...

September 26, 2022

How Journalism is joining forces with AI to fight online...

September 14, 2022

How cash deals between big tech and Australian news outlets...

September 1, 2022

Panel debate: Should journalists be activists?

August 19, 2022

Review: The dynamics of disinformation in developing countries

August 9, 2022

Interview: Are social media platforms helping or hindering the mandate...

July 15, 2022

Policy brief from UNESCO recommends urgent interventions to protect quality...

July 5, 2022

EJO’s statement on Ukraine

February 28, 2022

Testing Large Language Models (LLMs) for disinformation analysis – what...

August 26, 2025

Recognising manipulative narratives: two perspectives on disinformation in Europe

August 22, 2025

What is a “good story” in times of war?

July 31, 2025

Perspectives of invasion: media framing of the Russian war in...

July 26, 2025

New elections in Romania: Coordinated online campaigns once again

July 24, 2025

The new tool helping outlets measure the impact of investigative...

October 22, 2023

Audit of British Tory MP demonstrates the power of investigative...

September 13, 2023

The impact of competing tech regulations in the EU, US...

September 12, 2023

Enough ‘doomer’ news! How ‘solutions journalism’ can turn climate anxiety...

August 31, 2023

Student perspective: How Western media embraced TikTok to reach Gen...

August 19, 2023

Lessons from Spain: Why outlets need to unite to make...

July 26, 2023

INTERVIEW: Self-censorship and untold stories in Uganda

June 23, 2023

Student Perspective: Job insecurity at the root of poor mental...

June 9, 2023

The battle against disinformation and Russian propaganda in Central and...

June 1, 2023

Opinion: Why Poland’s rise on the Press Freedom Index is...

May 17, 2023

From ChatGPT to crime: how journalists are shaping the debate...

April 25, 2023

Student perspective: Supporting the journalists who face hopelessness, trauma and...

April 13, 2023

Interview: Why young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina feel they...

March 29, 2023

Humanitarian reporting: Why coverage of the Turkey and Syria earthquakes...

March 8, 2023

How women journalists in Burkina Faso are making a difference...

January 11, 2023

Dispelling the ‘green’ AI myth: the true environmental cost of...

December 29, 2022

New publication highlights the importance of the Black press in...

December 12, 2022

The enduring press freedom challenge: how Japan’s exclusive press clubs...

September 26, 2022

How Journalism is joining forces with AI to fight online...

September 14, 2022

How cash deals between big tech and Australian news outlets...

September 1, 2022

Panel debate: Should journalists be activists?

August 19, 2022

Review: The dynamics of disinformation in developing countries

August 9, 2022

Interview: Are social media platforms helping or hindering the mandate...

July 15, 2022

Policy brief from UNESCO recommends urgent interventions to protect quality...

July 5, 2022

EJO’s statement on Ukraine

February 28, 2022

13 Things Newspapers Can Learn From Buzzfeed

April 10, 2015

How Data Journalism Is Taught In Europe

January 19, 2016

Why Journalism Needs Scientists (Now)

May 13, 2017

Digitalisation: Changing The Relationship Between Public Relations And Journalism

August 6, 2015

Tabloid vs. Broadsheet

March 7, 2011

The new tool helping outlets measure the impact of investigative...

October 22, 2023

Audit of British Tory MP demonstrates the power of investigative...

September 13, 2023

The impact of competing tech regulations in the EU, US...

September 12, 2023

Enough ‘doomer’ news! How ‘solutions journalism’ can turn climate anxiety...

August 31, 2023

Student perspective: How Western media embraced TikTok to reach Gen...

August 19, 2023

Lessons from Spain: Why outlets need to unite to make...

July 26, 2023

INTERVIEW: Self-censorship and untold stories in Uganda

June 23, 2023

Student Perspective: Job insecurity at the root of poor mental...

June 9, 2023

The battle against disinformation and Russian propaganda in Central and...

June 1, 2023

Opinion: Why Poland’s rise on the Press Freedom Index is...

May 17, 2023

From ChatGPT to crime: how journalists are shaping the debate...

April 25, 2023

Student perspective: Supporting the journalists who face hopelessness, trauma and...

April 13, 2023

Interview: Why young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina feel they...

March 29, 2023

Humanitarian reporting: Why coverage of the Turkey and Syria earthquakes...

March 8, 2023

How women journalists in Burkina Faso are making a difference...

January 11, 2023

Dispelling the ‘green’ AI myth: the true environmental cost of...

December 29, 2022

New publication highlights the importance of the Black press in...

December 12, 2022

The enduring press freedom challenge: how Japan’s exclusive press clubs...

September 26, 2022

How Journalism is joining forces with AI to fight online...

September 14, 2022

How cash deals between big tech and Australian news outlets...

September 1, 2022

Panel debate: Should journalists be activists?

August 19, 2022

Review: The dynamics of disinformation in developing countries

August 9, 2022

Interview: Are social media platforms helping or hindering the mandate...

July 15, 2022

Policy brief from UNESCO recommends urgent interventions to protect quality...

July 5, 2022

EJO’s statement on Ukraine

February 28, 2022

On Social Media Propaganda Spreads Faster Than Truth

May 12, 2015

Reporting Hate Crime: Informing, Not Inciting

February 2, 2016

Egypt: Coronavirus and the media

March 20, 2020

How college students can help save local news

May 30, 2022

Comment: Media Aid? Or International Politics?

October 24, 2017

Operated by

Funded by

Newsletter

Find us on Facebook

Archives

Links