Amidst recent political and social upheavals, younger journalists in the UK consider roles such as ‘advocating for social change’ and ‘to speak on behalf of the marginalised’ as more important than their older colleagues, according to the report, UK Journalists in the 2020s: Who they are, how they work, and what they think. The findings of the report reveal a generational shift, while traditional values such as objectivity have also been questioned in the face of global challenges.

Providing significant insights into UK’s current media landscape, UK Journalists in the 2020s: Who they are, how they work, and what they think, is based on a survey conducted in late 2023 with a representative sample of 1,130 UK journalists, and is a follow-up to a similar survey in 2015. Edited by Neil Thurman, Imke Henkel, Sina Thäsler-Kordonouri, and Richard Fletcher, the survey is the UK leg of the third wave of the Worlds of Journalism Study, a global project researching the state of journalism across 75 countries.

Among the key findings of the report are changing conceptions of journalists’ roles and professional standards, increasing employment precarity, lingering inequalities between specific groups in terms of pay and seniority, and the continued adoption of new technologies that bring benefits but also exacerbate risks. Questions on UK journalists’ safety and well-being were also introduced, compared to the 2015 survey. Significantly, only 18% of UK journalists reported they had ‘never’ experienced safety threats related to their work over the previous five years, with the most frequent forms of safety threats experienced by journalists were ‘demeaning or hateful speech’ (45% had experienced at least ‘sometimes’), followed by ‘public discrediting’ (39%) and ‘other forms of threats and intimidation’ (16%). The report also spotlights continuing industry debates surrounding ethics of UK journalists, with many UK journalists expressing a weakened commitment to a universal professional ethos in 2023, compared to 2015.

EJO recently spoke with Lea Hellmueller, Associate Professor of Journalism and Associate Dean of Research at City St George’s, University of London, who co-authored two chapters on how UK journalists perceive their roles in society, and UK journalists’ views on ethics and acceptability of questionable reporting practices, to learn more about the findings on journalists’ changing roles and perceptions on ethics.

EJO: The report documents how journalists gave increasing importance to activist roles compared with the 2015 survey. Can you tell us what is changing about the way UK journalists perceive their role in society?

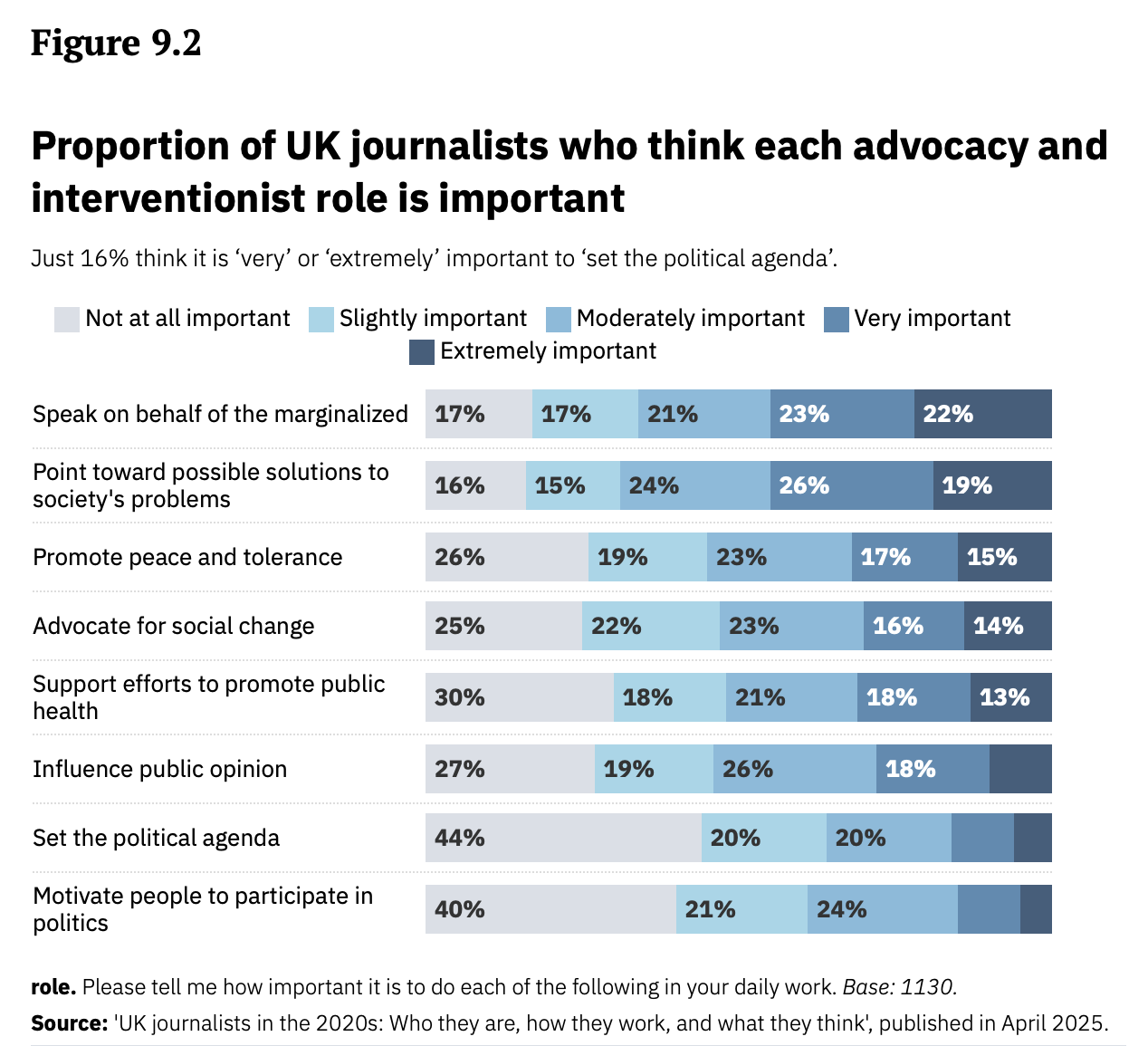

LH: I think it’s important to highlight that journalistic roles depend on many factors, including the type of medium journalists work (podcast, radio, digital, etc), employment status, and as we have written about in the report; generational differences. Over the last 8 years, we find a shift towards more activist roles and moving away from roles related to the idea of objectivity. Noticeably, there is a clear generational shift happening: While 74% of respondents over 40 rate their role as detached observers as very or extremely important, just 60% of those under 40 do.

Talking about role ideals that are related to activism such as speaking on the behalf of the marginalised or shining a light on society’s problems, we find that, statistically, these roles are significantly more important to younger UK journalists, leaning away from objectivity. This has been changing for some time now, so this is not something new. Together with my co-authors, I have documented a shift away from objectivity toward a transparency-oriented journalistic field in 2013. In this report, we found that younger journalists and journalists who are more exposed to working online are far less likely to say that objectivity is the most important value to them.

I think that has to do with journalists no longer holding this monopoly on informing the public – the gatekeeping role has been challenged. Many readers find news based on algorithms. We are dealing with a fragmented audience. At the same time, we are dealing with increased challenges including climate emergency, global and local geopolitical conflicts and war, and increased physical and psychological attacks on journalism worldwide. These challenges are difficult to cover with an objective voice and can potentially lead to reinforcing the status quo rather than providing a democratic function to the public.

It gives me hope as a journalism educator that especially younger generations seem to be keen to challenge certain beliefs, want to investigate stories by including marginalised voices, and invest in the future of journalism with their skill sets to make it sustainable for the future.

Figure 9.2 of the UK Journalists in the 2020s report showing the proportion of UK journalists who think each advocacy and intervention role is important.

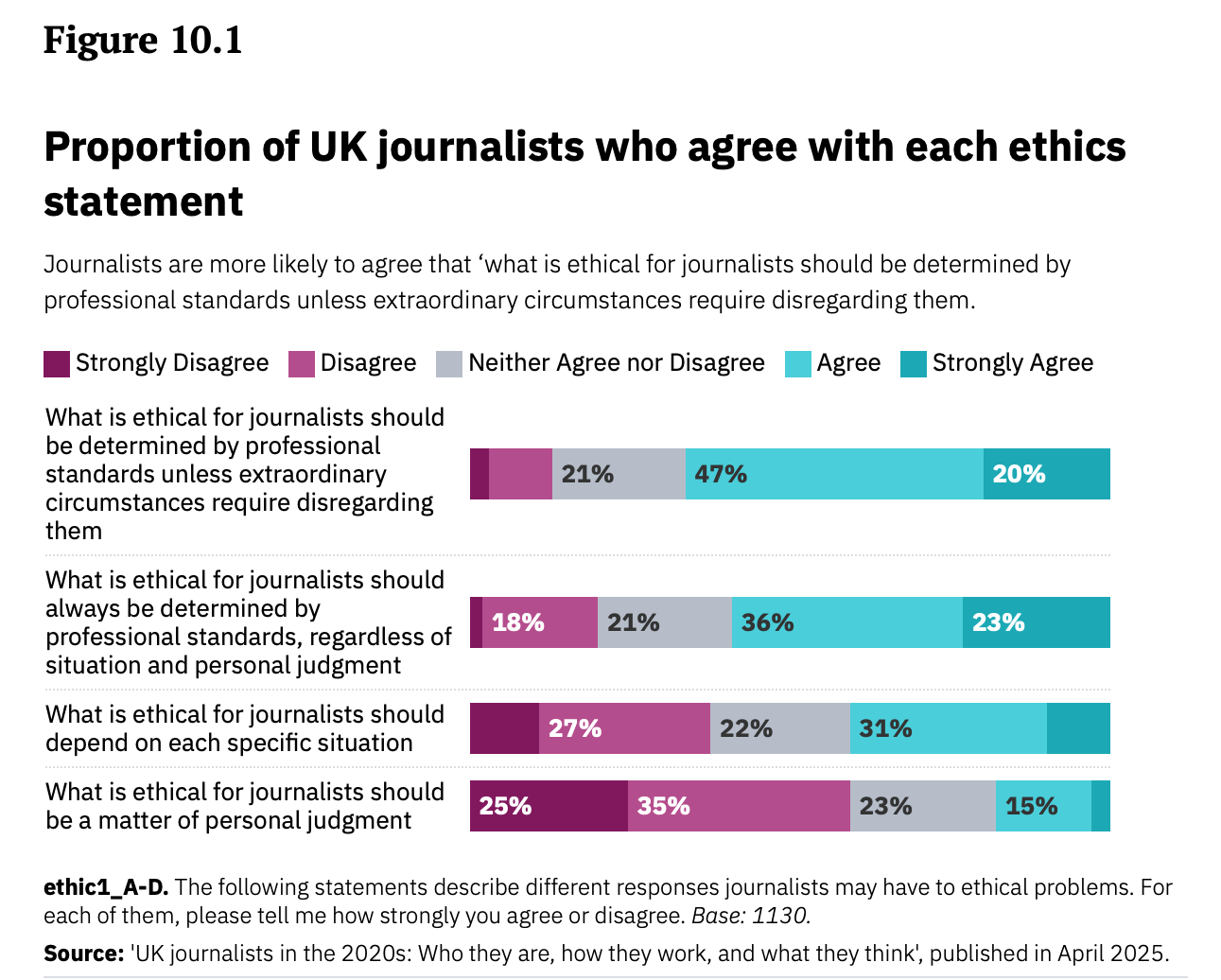

EJO: Something I found significant is how there’s a growing ambivalence around industry codes, especially when compared to the 2015 survey. The report documents that journalists are more likely to agree that what is ethical should be determined by professional standards unless ‘extraordinary circumstances’ require disregarding them. Can you tell us more about this, what are some reasons for it, what are these ‘extraordinary circumstances’?

LH: I think it’s a relevant question that deserves further attention – from the industry and academia. With our survey results, we are not able to answer this question, because we didn’t specifically ask about what the reasons are. We can only speculate about specific reasons. I hope and anticipate having future discussions and panels about this topic as it seems to be very relevant for the industry.

To provide some context: our survey results point to diminishing commitment to always adhering to codes of professional ethics. How do we know that? In 2023, UK practitioners were more likely to agree that ‘what is ethical for journalists should be determined by professional standards unless extraordinary circumstances require disregarding them’, nearly twice the proportion who agreed with a comparable statement in 2015. In other words, back in 2015, there was stronger support for journalists to always adhere to codes of professional ethics, regardless of situation and context. So there is a shift away from always following ethical codes to forms of more situational journalism ethics where extraordinary circumstances may be able to override these professional ethics.

Of course, we do know that Covid-19 happened as well as many other unexpected events that required journalists to do something that was different to what we knew before. That could have led to some of that ‘unexpected circumstances’ being understood as that, but we don’t have the empirical evidence. Internal journalistic chilling effects could impact an environment where journalists may not cover stories or sources out of fear of legal action and consequences (Kim & Shin, 2022). Ethical decision-making might be particularly impacted by shifting concerns over safety of journalists and their sources.

Figure 10.1 of the UK Journalists in the 2020s report showing the proportion of UK journalists who agree with each ethics statement

I think it’s really nicely written in the Foreword by Pete Clifton where he said that we just hope that it’s not because journalists are more under safety risks and threats that they are not always able to follow [these professional standards]… In other words, chilling effects can have an impact on the way stories are covered. Chilling effects can lead to journalists not covering certain stories or sources out of fear of legal actions and consequences and ethical-decision making might be particularly impacted by shifting concerns over safety of journalists and their sources. This is something we need to keep an eye on and which informs part of a global study on freelance journalists that I’m involved in to understand the precarities and the impact of forms of precarities of the news stories the public gets to read and consume.

EJO: Just to add, this is what’s written in the Foreword: “Now journalists more frequently say they will follow professional standards unless ‘extraordinary circumstances require disregarding them’. We can only speculate what those circumstances might be, but, of course, it can never be because of threats. These, it would seem, are more prevalent than ever, with only 18% of UK journalists saying they have never experienced safety threats related to their work”

LH: There’s a kind of chilling effect. I think that is one of the concerns as described above and I think it’s important to take this question seriously as it can impact the future of the journalism industry.

EJO: Is there a difference between how freelancers and those on permanent contracts may view industry codes?

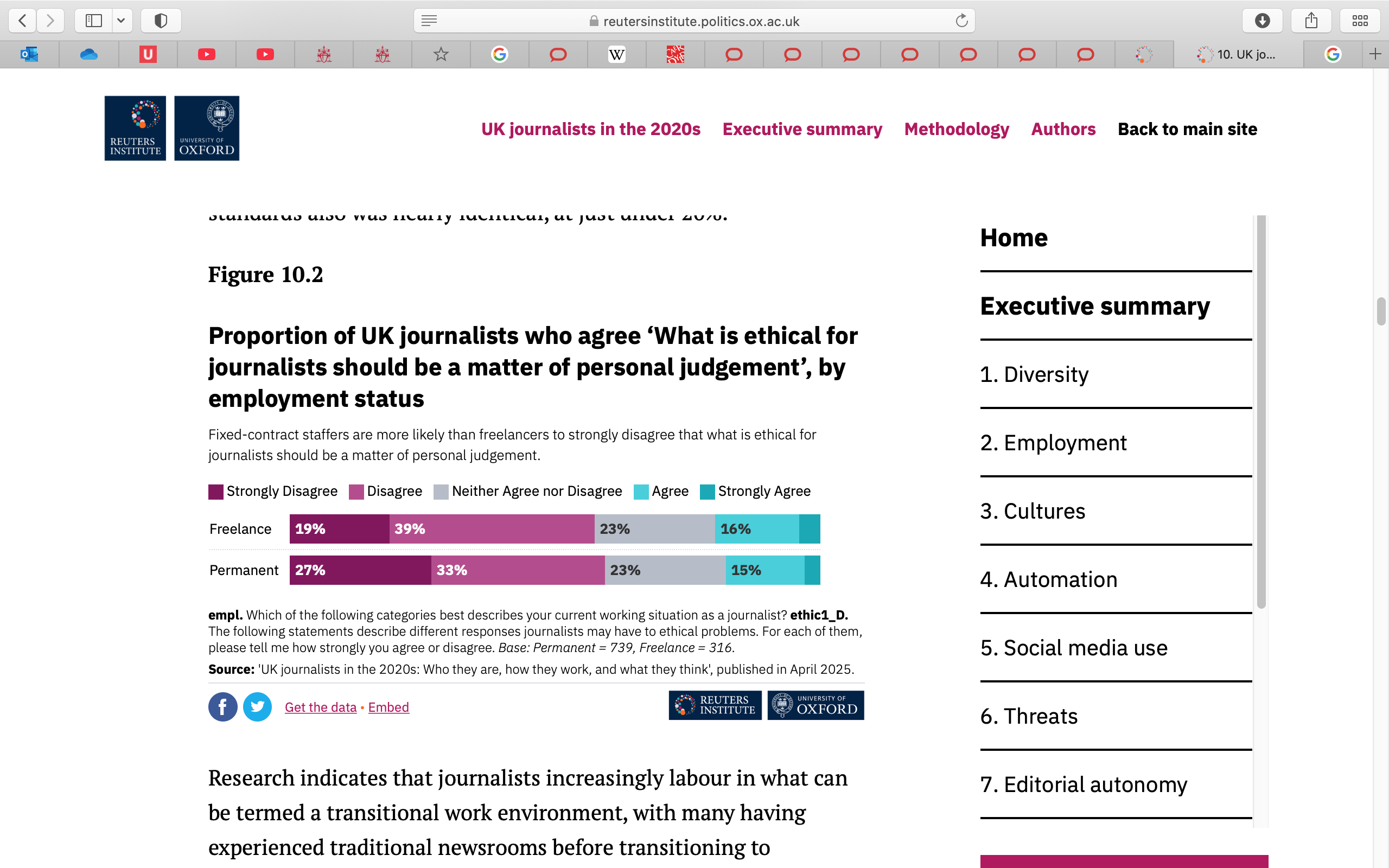

LH: The number of freelancers has gone up quite a bit in the last eight years, from 17% of respondents in the 2015 survey to 28% in 2023. No wonder that freelancing is oftentimes described as one of the few growth sectors in journalism. However, despite working differences (mostly working remotely for various clients, etc), the survey data suggest that freelancers and staff journalists share broadly similar views on whether and when questionable reporting practices – such as payments, inducements, and verification – are justified.

It is probably important to say that research indicates that journalists increasingly labour in what we call a transnational work environment, so they may have experienced traditional newsroom cultures before merging into independent work and vice versa. Meaning that freelancers and staffers may therefore have had similar exposure to considerations of ethics and regulation.

Figure 10.2 of the UK Journalists in the 2020s report showing the proportion of UK journalists who agree ‘what is ethical for journalists should be a matter of personal judgement’, by employment status.

Also what’s interesting is this other chapter we didn’t write – we asked journalists what should influence your work the most, and I think ethics is at the top. So we understand and know that journalists really rely on ethics as an important source of their professional identity as a journalist and I take this as a promising sign for the future of the industry.

EJO: Following on from that, the 2023 survey shows that there is a disparity between how male and female journalists respond to ethical choices they face, and how they would make different ethical choices. How would such disparities impact journalists’ practices?

LH: I think it’s possibly important to say that, when we think about gender, we found that it matters more than employment status like freelancer versus permanent contracts in terms of how journalists perceive those ethical practices. I think one of the problems interpreting the result is that, in our survey, more of the male journalists were in management positions or also working in hard news beats. That could also be something that impacts the way ethics is perceived and we have to consider intersectionality of class, gender and race. Here we tested for gender, but we will have to provide more nuanced analysis to understand the interconnected nature of social categorizations including gender.

We also need more nuanced approaches to understand gender identity and expression. For example, you can see that we had included the category of gender non-conforming journalists, but it was very difficult to analyse because we didn’t get enough respondents in that specific category. So most of our analysis tends to focus on females and males, whereas the reality might not be as binary. You can also see that the older and more experienced UK journalists in the sample were men, so that could also have an impact on why here’s a difference in terms of ethics.

We have known for quite a long time in journalism research that when we look at objectivity, it’s been considered a masculine way of knowing. This means that objective reporting may reflect and reinforce experiences and values of those in power oftentimes males, which can reduce the visibility of other perspectives and limit marginalised views to be represented.

We do know from previous research, for example, that transparency and probably also some types of activist roles are more of a female way of knowing validating and including the experiences of females, so there are certain patterns that emerge in the survey that were already known to us from previous literature and journalism studies, but it was interesting to see there.

EJO: I think it’s interesting how the report documents some changes, but also shows how some things have remained the same. Were there any findings that you found particularly surprising or shocking?

LH: I was positively surprised about the group of freelancers, how they’re quite similar to the other journalists in our sample. We expected them to be a bit different from journalists with permanent contracts when it came to ethics, but we weren’t really sure which direction it would take. So it could be that because they’re freelancers, maybe they don’t have to really follow the ethical codes as closely as journalists with permanent contrasts. Or because they’re freelancers, they would want to sell their stories to news organisations, so that they follow it even closer. I think I had expected more differences among freelancer, permanent, and temporary staff positions.

I was also surprised – and we discussed this already – about ethical codes being second to extraordinary circumstances. It was surprising to see it so clearly in the data.

Also, it is important to mention a bit about chapter 6, on the safety threats experienced by UK journalists and their physical, emotional, and mental well-being. It’s the first time actually that this was done. In 2015, we didn’t look at safety risks like harassment, stalking, and digital threats, and of course, those are interesting results.

Also when you look at gender, how women are more impacted, it wasn’t really possible to go too much into ethnicity because there weren’t big enough groups to calculate those tests. But I think it’s quite an important chapter as well to mention because it was the first time that data on that was collected. Last year was the year with the highest journalist being killed since the Committee to Protect Journalists started collecting data. I think it’s a real concern and of course there have been discussions at UNESCO and other International NGOs and that there needs to be something done about this.

EJO: What other research will come out of this?

LH: We’re going to present a new study at the International Communication Association in June in Devnver (USA), which is about the differences and similarities about ethical decision making in the US and UK – comparing those surveys and also trying to explain the trend toward leaving ethical codes behind when there are extraordinary circumstances requiring it. We are particularly interested in knowing more about these extraordinary circumstances as it seems to some extent counter-intuitive to the other finding that journalists find ethics as most important in defining their professional practice.

We’re also conducting qualitative interviews with journalists who moved from one country to another, and how they adjusted to new ethical decision-making processes, mostly because in the past we’ve seen quite a few journalists who are trained in the UK moving from the UK to US news organisation like Washington Post, CNN and so on and working there.

We’re also conducting a study with freelance journalists around the world – we have just finished the survey, which also specifically looks at safety and threats and ethics of care of media organisations.

And we want to connect our research to our teaching: I am teaching journalism ethics to almost 300 postgraduate students at City St George’s. This report will be informative for my own teaching. Some of my students already read it and got in touch with me, which was a very nice surprise, and I was very happy in discussing the findings with them. I envision to survey my future students to see how much they align with the survey results and what might be crucial to understand for journalists in the future.

The publication is available here: UK Journalists in the 2020s: Who they are, how they work, and what they think

Other news articles on the publication include: Young UK journalists lean towards activist roles, away from objectivity – new survey.