Deep skepticism surrounds the new media freedom reforms passed earlier this year in Turkmenistan. The first such law ever to be passed by the nation, it promises freedom of expression and a ban on all media censorship, but is generally believed to be too disconnected from the country’s dark reality to inspire much hope for change. The new law appears to champion the ideals of a free and independent media, yet its promise of near absolute freedom is a complete political backflip for a nation characterized by extreme censorship and its mistreatment of outspoken journalists. Despite the good intentions of the new Turkmen law, it can’t help but seem too big a first step to overcome a history of repression and hostility toward media. Many press freedom groups regard the move as an empty stunt to appease the international community rather than a serious attempt at reform.

Reporters Without Borders consistently rank Turkmenistan at the very bottom of their annual Press Freedom Index. Trailed only by Eritrea and North Korea in their 2013 review, this closed and repressive country has been criticized by the organization for the government’s monopolization and control of the media. Turkmenistan has been similarly reprimanded by media watchdog Freedom House, whose 2012 report “Worst of the Worst Repressive Societies” reported that, “freedoms of speech and the press are severely restricted by the government, which controls all broadcast and print media.” Prior to January 25, 2013, all of Turkmenistan’s media outlets, including radio, television and newspapers, were owned and controlled by President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov. The one privately-owned outlet was subject to rigorous government screening despite its focus on business and entrepreneurial affairs. The new law seeks to prevent the “monopolization of the media by persons or entities” and states that any member of the public may now own or buy shares in a media company. It even goes as far as to say that the government will provide subsidies for private investment in the industry. Another radical policy turn-around is the declaration of a person’s freedom of expression and that the media is implicitly “free.” No such concept had previously been established in the country, and the assurance that individuals will have “the right to use all forms of media to express their opinions and beliefs, and to seek, receive and impart information” could not be further from the repression and imprisonment of opinionated persons that has long been noted in the past. Reporters Without Borders secretary-general, Christophe Deloire, commented on these discrepancies saying, “for the time being, some of [the law’s] provisions, although very satisfactory on paper, border on the ridiculous when confronted with the reality of journalist practices.”

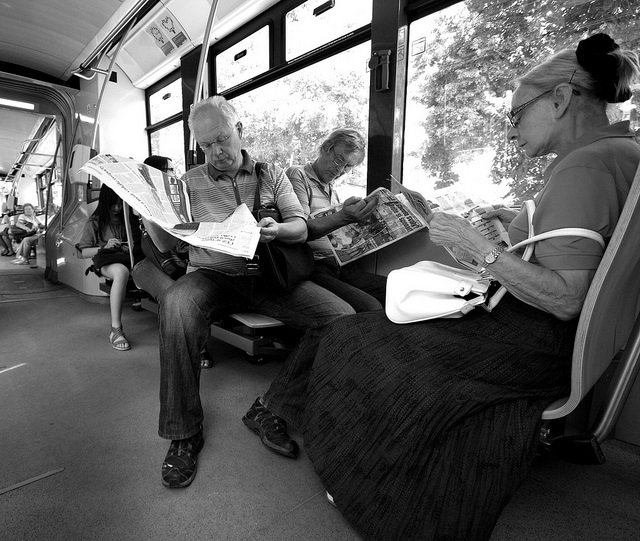

One article of the new law that appears to inspire more material hope for change is the section that guarantees Turkmenistan’s 5 million inhabitants access to news media from abroad. Internet, although available, is costly and rigidly controlled, while satellite dishes which once provided citizens the opportunity of channeling broadcasts from neighboring Russia and Turkey, were torn down in 2011 as “unsightly.” Starved for information, the people of Turkmenistan rely on word-of-mouth strategies to circulate news because they have such little faith in the government controlled media. The opening up of foreign networks and sources of information will be a radical improvement for the country and its people if it can be made accessible to the masses. Most concerning about the contradictory nature of the law is that one article states that the regulation of the media will remain state-run despite another section claiming that, “nobody can prohibit or impede the media from disseminating information of public interest.” There is also a clause that states all new freedoms imposed by the law may be revoked at will to “protect the constitutional order, health, honor and dignity of the private life of citizens and public order.” These contradictions severely damage the credibility of these reforms and justify fears that they will not be a material step forward for this deeply troubled country. While many international media organizations and political bodies have come forward to support the intentions of this reform, they remain skeptical as to how much change it is likely to inspire/enable. Only time will tell what benefit, if any, the country may hope to profit from.

Photo credits: sarflondondunc / Flickr CC

Tags: Freedom House, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, Press freedom, Press Freedom Index, Reporters without Borders, Turkmenistan