Still from the documentary “War Photographer” (2001) by Swiss director Christian Frei

Every journalist has experienced a time when emotional intelligence became a more important element in news gathering and reporting than merely stating “the facts”. Whether they’re trying to persuade a reluctant interview partner to give a statement or dealing with unpredictable crowds whose dynamic can change at any moment, reporters need to do far more than just gather information. They also need to be able to perceive, understand and handle a situation emotionally. Journalism scholars – whose job is to observe how the boundaries of the profession are being redefined – are becoming increasingly aware of the extent to which the emotions make a positive contribution to news reporting.

Western journalists and journalism scholars have not always considered emotions and empathy to be positive and productive elements. In the past, many suspected that giving space to them could lead to sensationalism and “cheap emotions”. At best, it was acknowledged that reporters might have “a nose for news” or be able to rely on their “gut feeling” in journalistic decision-making. Some asked if it was permissible for journalists to adopt a compassionate stance in specific circumstances.

Martin Bell, who covered the 1990s Balkans war for the BBC, proposed a “journalism of attachment” as a way of taking up a moral stance on behalf of the victims of war and conflict. However, this did not have much of an impact on mainstream journalism practice until the past decade. In 2001, US journalism scholar Michael Schudson defined journalism as being “cool, rather than emotional, in tone”, and in 2010 the British scholar Denis McQuail advocated an impartial journalism “avoiding value judgements or emotive language or pictures”. Journalism practitioners were keen to emphasise that objectivity and detachment were ideals that Western journalism should aspire to. For them, emotions belonged more to the commercial sphere.

But about a decade ago, this scenario changed, and in 2008 Schudson proposed “social empathy” as a more compassionate understanding of “how people very different from us experience their lives.”

Thinking and feeling

Perhaps now is the time to ask from a different and more general perspective: can emotions and empathy feature positively in journalism and journalistic work practice?

We can easily identify four major pathways in which emotions and empathy become essential qualities that journalists need to draw on. These combine aspects of neuro-biology, moral decision-making, professionalism, and the changing role of journalism in a society that encourages a more open expression of emotions. Before discussing what consequences this might have for journalism in general, let us first take a closer look at the four aspects.

First, emotions are part of our biological-cognitive perception system – and hence shape how we see the world. We understand the world both cognitively and emotively. We think and feel about issues. Hence, the way our reality is shaped involves the interplay of cognitions, emotions, perceptions and memories. Many experts have tried to explain why Britain voted pro-Brexit. However, explanations fail if they do not take into account “how voters feel” (Stephen Coleman). Empathy matters here in particular as a nonverbal mode of understanding the mental and emotional state of others.

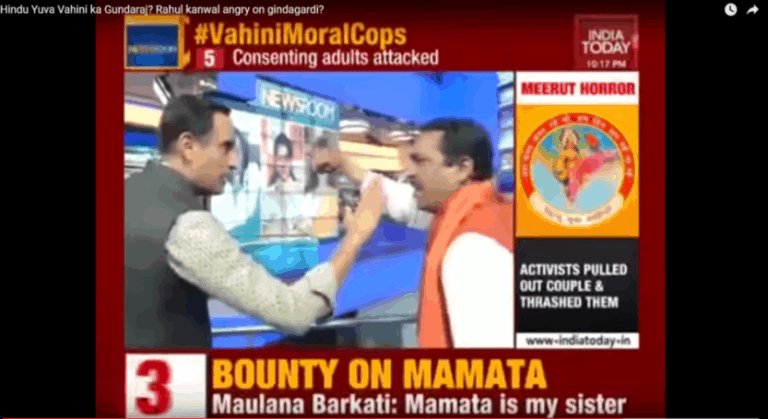

India Today investigative journalist and presenter Rahul Kanwal (left) engages in a lively debate with a politician

This applies especially to Indian journalism, which is more emotion-centred. A young anchor from the 24-hour news channel Headlines Today (now known as India Today) once told me that journalists reporting on those who become the focus of media attention need to understand what is being experienced by the subject of a story in order to be able to tell that story. Otherwise, “I don’t think a viewer can understand the emotions of what the person is going through”, she said. Empathy also helps in verifying statements – it is not always easy to judge if someone is lying or telling the truth, and a good sense of emotion-reading helps.

Empathy becomes here what we can call – taking our cue from the French philosopher and sociologist Pierre Bourdieu – “emotional capital”. This means that journalists who possess a higher degree of emotional capital (understood positively as emotional intelligence) are likely to make a greater impact on the profession than those who do not.

A senior British journalist working in regional news once told me that, having done “hundreds of door knocks where people have died… If you actually are sensitive and behave like a fellow human being instead of a robot who wants a picture, then you are more likely to get a picture.” Journalists capable of empathy might be better at securing the cooperation of their subjects, as they are able to spot more subtle nonverbal forms of information.

In brief: empathy as a journalistic work resource shapes professional and ethical decision-making to a much greater degree than we had previously assumed.

The impact of emotions on professional judgement

The contribution of empathy and emotions to journalism does not stop at neuro-biology. A second important field is moral decision-making. Journalists have to be able to make judgements about the ways in which we humans are affected by certain situations. The scholar Renée Jeffery has found that already at the time of the Scottish Enlightenment, David Hume highlighted the role played by the emotions in the human mind’s ability to make judgements. Hence, acting ethically is emotion-motivated and reflects an “innate sense of right and wrong”. For example, remaining impartial is an inadequate response to Trump’s sexism and racism. In this case, there are not really two sides to a story, and sticking to the classic principles of journalism is not an adequate response.

Nor can journalists remain impartial when it comes to climate change coverage: we cannot give equal weight to both scientists and climate change sceptics. In this case, a journalist who lacks a built-in moral compass becomes a morally questionable entity. This is where artificial intelligence (or algorithmic journalism) has so far failed – despite it being a sequence of apparently logical decisions, its capacity for judgement remains poor.

But we also need to consider the extent to which journalists are aware of the impact of their own emotions on their decision-making. Understanding how our emotions influence our professional judgement is important if we are to produce journalism that transcends our personal subjective outlook. The psychologist Ziva Kunda has shown how emotions and “affects” interact with reasoning and belief. Kunda used the term “motivated reasoning” to describe how humans (and, hence, potentially journalists) might cling to false beliefs in the face of all evidence to the contrary in order to minimise uncomfortable cognitive difference. When journalists are largely left to their own devices to regulate their emotive setup during professional work, this can influence news coverage.

Unwritten rules

Third, emotions come into play in style of presentation – especially in broadcasting, where a set of subtle rules governs the extent to which emotions form part of the presentation style. For instance, the more sober “cool” style of the British BBC News at Ten differs considerably from the loud and colourful “market crier” style often seen on some Indian news channels. Here, journalists engage in “emotional labour” – a term coined by the sociologist Arlie Hochschild in her 1983 book The Managed Heart and used to refer to the practice of managing one’s own emotions as required by certain professions.

Flight attendants, who are expected to smile and be friendly even in stressful situations, constantly engage in “emotional labour”, but journalists too are often required to display an “appropriate” emotional response to a given situation. These unwritten rules governing the display of emotion vary according to the cultural context and the news organisation. They mark the implicit boundaries of the journalistic profession in different cultural settings, and a sound grasp of these rules is essential in order to fit in and appear “professional”.

Fourth, the turn to a more “affective society” (Clough and Halley, 2007) is fundamentally changing the role of journalism. When commercial pressures make audience engagement an essential requirement, when populist leaders hijack the public sphere by riding a wave of collective emotions, quality journalism needs to seek new paths beyond the purely cognitive-focused information dissemination and inverted pyramid models. But where do we go from here, and how can journalists harness their emotions and empathy more productively?

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared on the EJO’s French-language site. In a subsequent article, Antje Glück will describe some of the ways in which the issues she outlines here are now being addressed in the training of journalists.

References

Bell, M. (1998). The journalism of attachment. In Kieran M. (Ed.), Media Ethics, London & New York: Routledge, 15-22

Clough, P. T., & O’Malley Halley, J. (Eds.) (2007). The Affective Turn. Theorizing the Social. Durham: Duke UP.

Coleman, S. (2013). How Voters Feel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hochschild, A. (1983). The Managed Heart. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jeffery, R. (2014). Reason and Emotion in International Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kunda, Z. (1990). “The Case for Motivated Reasoning”. Psychological Bulletin. 108 (3), 480–498

McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory (6 ed.). Los Angeles & London: Sage

Schudson, M. (2001). The objectivity norm in American journalism. Journalism, 2 (2), 149-170

Main image: Christian Frei | License: CC BY-SA 2.0 | Source: Flickr

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO.

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in Can Journalism Make Audiences Care?

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Tags: affective society, Arlie Hochschild, BBC, compassion, David Hume, emotional intelligence, emotional labour, empathy, ethics, India Today, moral compass, morality, motivated reasoning, objectivity, Pierre Bourdieu, professional judgement, Renée Jeffery, Scottish Enlightenment, Stephen Coleman, Ziva Kunda