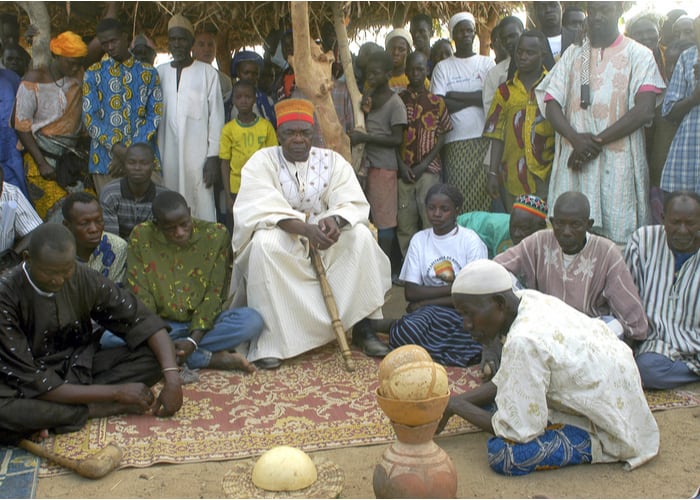

KOKEMNOURE, BURKINA FASO – FEBRUARY 24: Establishment of the new chief of village of Kokemnoure. Andre Silga the new chief will hear the history of his line of chief by the griots, february 24, 2007

There are various perspectives on the increasing academisation of journalism training. However, the fact that one must learn the profession in some form before joining it, is probably undisputed. But this view is not necessarily universal. In West Africa, for example, if you are a descendant of a ‘griot’ your birthright automatically qualifies you to enter journalism.

The griot tradition has existed since before colonial times and can be described as a social communication role. Today, in addition to being journalists, griots are diplomats, teachers, advisors to rulers, musicians, poets, entertainers, and masters of ceremonies. They mediate between the people and those in power, teach various groups about the history and culture of their country, and report on current events.

From door to door

The origin of the term griot is still unclear. According to the researcher, Thomas Hale, it first appeared in the fourteenth century. Mentions of the presumably related word “guiriot” then appear from French missionaries and colonial administrators in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It seems that different African cultures have their own terms for the social role, but it remains unclear whether the term “griot” originated in Africa or comes from the early cultural exchange between Europe (especially Portugal) and Africa.

Officially, my friend Demba is also a griot. His family has carried out this role in Senegal for a long time. However, he has little to do with the traditional role. He is currently training to become a nurse. Nevertheless, he remains a griot by birthright. But there are griots who are still working in Senegal today, Demba tells me. They go door to door in their communities to spread information such as the birth of a child. They are responsible for ensuring that the information is accurate and reaches its intended audiences.

Moving away from the pyramid

The griots tradition is interesting – particularly because it has remained a predominantly oral profession, with Terje Skjerdal describing the practice as “journalism based on oral discourse”. But what is also interesting is how stories are structured and told in a traditional form. This is in contrast to the Western journalism “inverted pyramid” – the archetypal informational structure of news, which opens with the most important information, followed by the source, details, and the general background. Instead, griots tell their stories, according to renowned media and journalism researcher, Marie-Soleil Frere, less hierarchically structured and using literary devices such as parallelism and repetition.

This is because their reporting is not unidirectional, like, for example, the typical broadcast news reports. The griots have been incorporating for centuries what journalism in Germany and other Western countries is currently working hard to achieve – interactivity. They encourage their audiences to join in, heckle, and sing along.

When elephants fight…

To this end, they often refer to sayings and idioms that are widely used in their respective cultures. Frere observed these characteristics of story structure and repetition used by griots in newspapers in Benin and Niger. Analogies from nature, such as the saying “when elephants fight, the grass suffers”, are used to describe political processes and character traits of influential people. Other metaphors are borrowed from sports, nutrition, or even the literature used to describe disease – for example, the viral transmission of certain ideologies and attitudes.

And it is not only in print journalism that griots use metaphors and aphorisms. According to journalism academic, Wunpini Fatimata Muhammed, they also play a special role in radio programs in their indigenous language. There, for example, people are hired to translate scripts written in English into the respective language in real-time. They achieve this by using translation templates created with traditional and intertextually enriched formulations.

The griots and the praise song

Here too, a difference to Western journalism becomes apparent. While in the West “phrasemongering” – using unnecessarily flowery language and descriptions and using sayings instead of describing what is happening – is seen as a shortcoming to be avoided at all costs, among the griots and the journalists influenced by this tradition these literary mechanisms are seen as valuable tools.

Griots use metaphors, which are widely known in their communities and therefore can be easily understood by their audience, to convey political and social contexts. Their use of figurative language and satire ‘de-sacralises’ those in power and make them susceptible to criticism. According to Frere, however, there is a danger that an excess of metaphors can also oversimplify contexts and reproduce stereotypes.

And that is not, from the viewpoint of Western standards, the only concern about griots and today’s journalists in West Africa who are inspired by the tradition. They have gained a reputation for being, in the worst case, little more than praise singers for their masters – meaning they are considered fundamentally uncritical and/or biased.

However, this perspective is contested by, among others, previous media and politics lecturer and now chairman and information commissioner at the Right to Access Information Commission in Sierra Leone, Ibrahim Seaga Shaw. He points out that the griots, at least traditionally, have had a strong focus on sarcastic and satirical criticism of those in power and that this function is actually embedded in their social role – as long as the criticism is rooted in the values of the community in question.

The focus on opinion

This highlights another characteristic of the reporting done by griots and their journalistic descendants – that is, it places a strong emphasis on opinion and analysis. Frere demonstrates this when she outlines how in Beninese newspaper reports on their new constitution, there is hardly any information on its actual content. Instead, there are detailed comments on certain perceived peculiarities in the constitution, and the reports seem to require the audience to be already familiar with the information in the constitution.

In summary, the work of the griots and the journalistic form that is modelled on it differ systematically from Western standards. Differences lie in the use of clichés and figurative language, the structuring of narratives, the relationship between opinion and information, and the degree of distance from audiences.

But these differences should not be hastily classified as negative or deficient. Contextual conditions in the sense of ethnic differentiation and social dynamics can certainly justify different approaches. And perhaps it is also worth taking a closer look at certain opinions that are firmly anchored in our practice, such as the condemnation of any cliché or circumlocution, and evaluating whether a positive and thus a legitimate field of application could not also be wrested from them.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO or the organisations with which they are affiliated.

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in: Why the UK government’s new school curriculum resource body should partner with the BBC

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Tags: African journalism, ethics of journalism, griots, Journalism in a Global Context, Journalism Practice