The Czech Radio podcast series “Dataři” looks at innovative uses of data.

Speed and clarity: it’s a basic tenet of journalism that you need to turn a story around as quickly as possible and that the end result has to be crystal-clear. So where does this leave data journalists, who spend most of their time immersed in huge amounts of complex data?

“We could end any of our projects with a line saying: ‘It’s more complicated'”, is how Petr Kočí of Czech Radio’s data journalism team sums up the challenges he and his colleagues face.

EJO asked Kočí and his fellow team member Jan Cibulka what it’s like to do data journalism in the Czech Republic. Among the questions we put to them were: How do you reconcile the often protracted and uncertain business of analysing data with the deadline-driven routine of a newsroom? How do you extract a clear headline from a mountain of information? And how do you go about finding interesting data?

At first sight, the work of Czech Radio’s data journalists does not look so very different from that of their non-data colleagues. Like all journalists, data journalists follow a story over a period of time and rely on a network of sources that include experts, politicians, NGOs, etc. On top of this, they have to work with other Czech Radio departments and provide the data they need.

One of the biggest challenges is discovering how to make an effective contribution to the daily agenda of the network as a whole. “Sometimes, there’s a story for which data is required. We could mine it quickly enough and would like to do more, but editors rarely turn to us for help,” Kočí lamented.

Caution needed

Data journalists’ work is often out of step with news values such as speed, intelligibility and clarity. “When you take a deep dive into the data, you often realise it’s not possible to explain it quickly and in simple terms,” Kočí said.

He cited a recent case arising from some statistics contained in the annual report of the State Institute for Drug Control. The figures implied that the consumption of antidepressants in the Czech Republic had increased dramatically in recent years. “A number like this sounds alarming to anyone not in the know and in a busy newsroom could easily end up producing a sensational headline,” he noted.

However, when the team asked a psychiatrist to account for what might lie behind the apparently dramatic increase, a different picture emerged. “In fact it’s not such a big deal. The new generation of psychopharmaceuticals has caused the increase in consumption because they can also be prescribed for other conditions,” Kočí explained. He added that great care has to be exercised when interpreting data, as situations like these can often arise.

An expensive toy?

One reason why few Czech newsrooms employ data specialists is that to do data journalism properly, you often have to devote a considerable amount of time to a task whose outcome is uncertain.

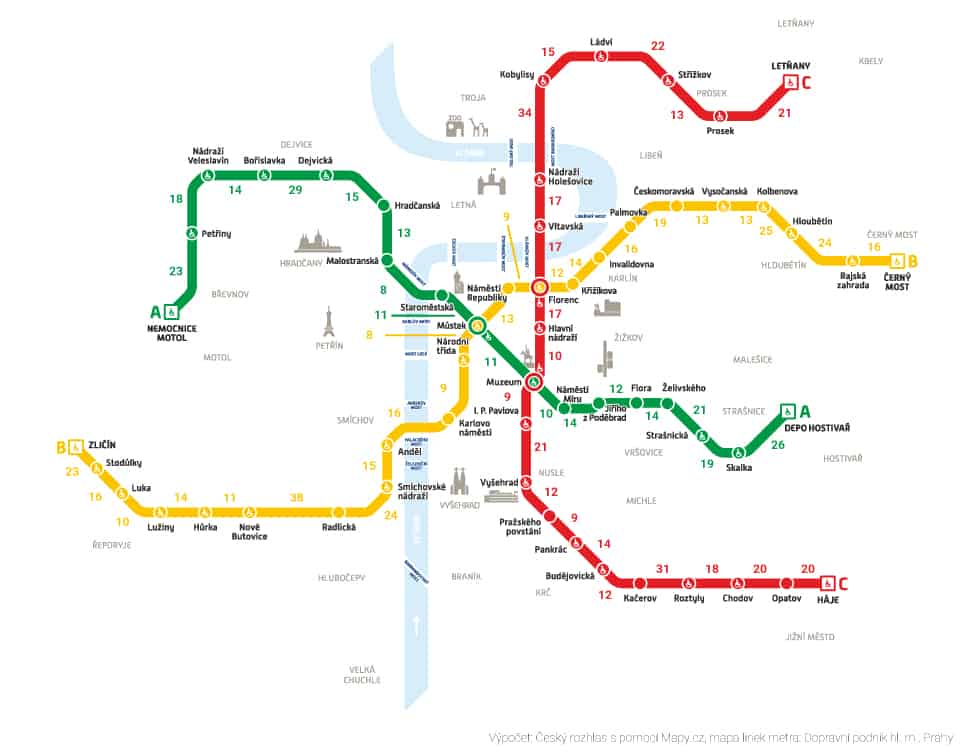

It’s often quicker by foot: a map created for Czech Radio’s website shows the time needed to walk between Prague metro stations

“Data journalism does not pay off within the current economic models of the Czech media. It makes more economic sense to hire a trainee to collect and republish press releases and other public relations material. It’s hardly quality content, but the sheer bulk of such material and the speed with which it can be churned out generate precious clicks,” Cibulka told EJO.

Czech Radio’s data team began life some years ago, as part of the right-of-centre daily Hospodářské noviny. The paper eventually decided to let the team go because of a lack of resources. The then editor-in-chief explained to them that having a data journalism department is like owning a shiny cabriolet: it’s an expensive toy that looks nice, but it’s no good for everyday use.

“There’s better support and more space for our work in the public service broadcaster than there used to be in a commercial outlet,” Kočí said.

Hospodářské noviny still does not have a dedicated data team, and instead relies on the efforts of a few statistics and infographics enthusiasts. Vltava-Labe-Media, another large publishing house, employs one data journalist. Other publishers and newsrooms rely on commercial statistical agencies.

Mining the data

Data comes from various sources, most of them online. “In my experience, about 80% of the data we use is mined online. That doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s easily accessible. You need more than just technical skills to access quality data,” Kočí noted, adding that for non-specialist journalists, the available data can often be difficult to read and interpret.

In a few cases, journalists collect the raw data themselves. One example of this is the project “How a marathon hurts“, in which an amateur runner was provided with sensors so that his vital signs could be monitored as he took part in an actual marathon. A doctor analysed the data collected in real time and gave a live commentary on the impact of such vigorous physical activity on the runner’s body. “Having access to the data meant the doctor was able to prevent him from collapsing,” Cibulka said.

The third and final way to harvest data is to request it from state bodies using the Freedom of Information Act. Although the authorities are obliged by law to provide information, the data team has on a number of occasions had to resort to legal means to force their hand.

“We have filed twelve lawsuits so far, and we could have filed more. However, the whole process takes time, and there is not much point in getting hold of data three years after you need it. The authorities know that by the time a court has reached its verdict, the data will already have passed its use-by date. And in some cases, the journalist who filed the original lawsuit has moved on by the time it is settled,” Cibulka explained.

Slow progress

The Czech authorities have been painfully slow to publish open government data. By 21 November 2019, only 38 entities (including state authorities, companies and city halls) had registered with the National Open Data Catalog operated by the Ministry of the Interior, and much of the data provided is incomplete.

“Much of the open data is just for form’s sake. Important information is often missing,” is Cibulka’s verdict on the willingness of the authorities to make state data readily available.

His experience is in line with the assessment of the international Open Data Barometer (ODB), which ranks countries according to their degree of data openness. In 2016, the ODB placed the Czech Republic in 31st place, awarding it only 44 points out of 100.

Images: Logo of Czech Radio Dataři podcast series created by TIMO / Infographic of Prague metro created by Czech Radio data journalism team. Reproduced with permission.

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in “Hack the newsroom”: Five lessons from doing data journalism in Portugal

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Tags: Data Journalism, Data Mining, infographics, Open Data, Open Data Barometer, Statistics