The New York Times, the last major US newspaper with a public editor – or ombudsman – has announced it is cutting the post, replacing it with a staff-run ‘Reader Centre’.

The recent news that The New York Times is eliminating the position of Public Editor—sometimes called an ombudsman, or reader’s representative—is sad but not at all surprising. Not too long ago, back in the 1980s, there were more than 40 American newspapers that had such a position. Their role was to look into complaints or observations from readers about substantive editorial issues and publish their findings. The idea was to hold newspapers accountable to their own editorial standards and to provide readers with an independent assessment of their observations.

Independent is the key word here. Today, there are no major American newspapers who support such a position. The New York Times, which was a reluctant late-comer to the public editor ranks in 2003 in the wake of a plagiarism scandal surrounding one of its reporters, was the last one. The numbers, in fact, had been declining for several years and accelerated rapidly after 2008 as the economic recession, combined with rapidly changing technology, took a heavy toll on newspaper finances and profitability.

Cutting the ombudsman probably seemed to be an easy call. It meant saving a slot, saving a salary probably equivalent to a senior editor’s, and getting rid of a frequent internal pain-in-the-neck all in one shot.

Although the Times’ decision puts the proverbial nail in the coffin of this position, the real death knell came in 2013 when The Washington Post ended its support of an independent ombudsman after 43 years.

Role originated on a Kentucky newspaper, 50 years ago

The Louisville Courier-Journal, in 1967, became the first newspaper to have a reader representative. But he served mostly as a conduit between readers and management and, as the Washington Post’s first ombudsman, Richard Harwood, would later describe the Kentucky staffer’s inside role: “He did not independently evaluate and critique the newspaper’s performance, nor did he publish confessions of error or moralistic sermons on the sinfulness of our trade.”

It was the Washington Post in 1970, under its then Executive Editor, Ben Bradlee, that established a truly independent, standard-setting ombudsman position—with a Sunday column that management didn’t see until it appeared in the paper–and encouraged a culture of acceptance of the value of such a role in a big and typically skeptical newsroom.

I spent 35 years at the Post, the last five, after I had retired from the staff, as ombudsman from 2000 through 2005. After that I became the first ombudsman at Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), where I stayed for almost 12 years. So that’s a lot of cranky readers, viewers and, at times, reporters and publishers. But, while I understand that the press landscape has changed dramatically, it still seems to me that the independent ombudsman has always been the best way for a news organisation to back-up its claims of accountability to its readers and viewers. This is also why I think the Times’ decision is wrong and why the establishment of a new, internal, staff-run “Reader Centre” will not replace the crucial independent journalistic investigation and public presentation of the ombudsman.

There is a reason for demanding independence. It is not a great career move for journalists to be publicly critical, when necessary, of their news organisation.

News organisations seek to hold government, industry and all American institutions to account and they need to do the same to their segment of our system of checks and balances.

Why I think the role of the public editor or ombudsman remains vital

In today’s anything goes online and social media environment, there is an abundance of press criticism. Some of it can be very good and penetrating. But a fair amount of it is wrong, coming from ideological, partisan or single-interest critics or sites that tell their readers or subscribers where to complain about what. They have little interest in improving journalism but rather promote points of view or tear down news operations that threaten them with strong, fact-based reporting. So an ombudsman these days can also engage not just in internal critiques but in defending their news organisations against widespread but inaccurate criticism.

Readers and viewers like to see their expressed concerns addressed by an experienced, independent person at the news outlet that they read or watch. That is where they look for a response, not to some web site or critic that they may never see, read or know anything about.

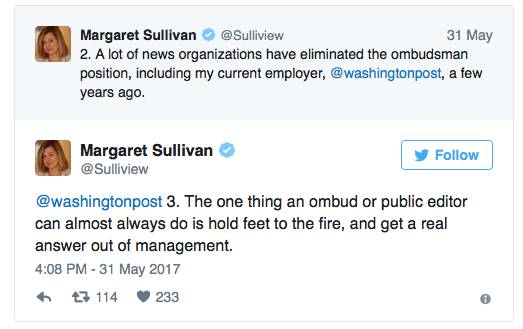

Margaret Sullivan, a former public editor of the New York Times, now with the Washington Post, reacts on Twitter to news that her former post has been cut.

Reporters and editors who work for news organisations that employ an ombudsman read what the ombudsman says because they know that their readers and colleagues will see it. They may not pay much attention to outside critics. And the presence of an independent ombudsman who publishes or posts regularly gives an added incentive to reporters and editors to make that extra effort to be beyond reproach journalistically before hitting the send button.

Similarly, ombudsman have a better chance than external critics of persuading editors and publishers to explain themselves, and to give on-the-record answers. Indeed, most media critics inside other news organisations these days rarely, if ever, write about their own organisations.

While the time of news ombudsman in this country has clearly passed, it seems to me that the decisions to eliminate these positions have not been good ones. Independent ombudsmen or public editors are still the single most effective check on press transparency and accountability, readers and viewers like them, they can cement readers to their newspaper and enhance the credibility of the news organisations. So it also seems to me to be good business.

An ombudsman shows that the press can take a punch, if necessary, not just deliver one, and that there is also an independent voice to counter the daily claims of “fake news” and to defend, when appropriate, against the sea of unfair and inaccurate criticism.

Image, Flickr CC licence: Scott Beale/Laughing Squid

Tags: independent journalism, Media Accountability, New York Times, ombudsman, PBS, Public editor, readers representative, Washington Post