Native advertising is more popular than ever before among advertisers and media companies because many users ignore conventional advertising such as banners and pop-up pages. Yet, native advertising is also a form of deception. Without knowing, users get content which isn’t purely journalistic. Instead, they consume advertising in disguise.

Unsurprisingly, native advertising has also attracted the attention of researchers. Two recent studies by Bartosz W. Wojdynski, an assistant professor of journalism at the University of Georgia, USA, and David A. Hyman, a law professor at Georgetown University have now looked at how the presentation of native ads influences whether users recognise them as such.

And the results are bleak. Both find that despite appropriate warnings, most media users do not recognise native advertising when they see it.

The Presentation Is What Counts

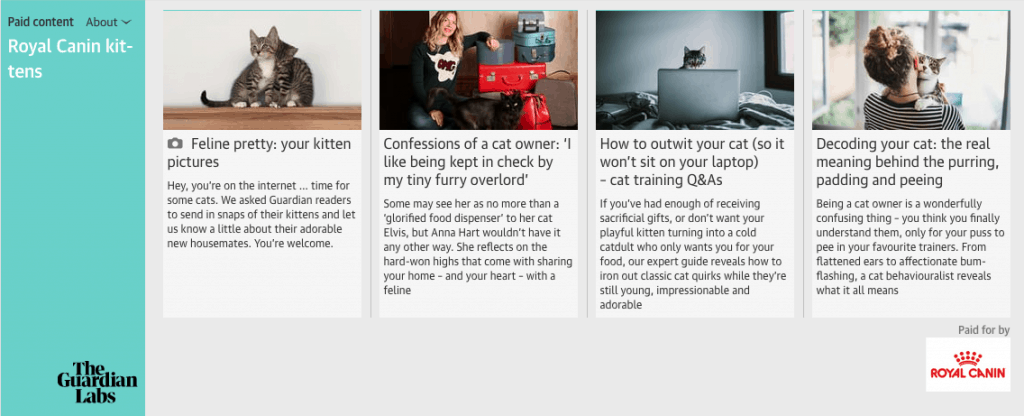

Previous research has shown that the presentation of native advertising makes a crucial difference when it comes to users being able to realise that they are in fact reading an ad. For instance, if the logo of the advertiser is present (and how prominent it is), affects the perception of readers.

In his study, Wojdynski tested four factors which affect the recognition of sponsored online articles. To this end, he created 24 versions of an online news story and varied the disclosure label of the sponsored article. The disclosure label varied between high („Paid Advertisement by – name of sponsor”) and low (“Partner Content by – name of sponsor”). On some articles, the logo of the advertiser was present while others went without one. To vary the visual prominence of the disclosure label, it was presented either in grey over white background, in the same font of the article, in font size 12 (low prominence), or in black, with a font clearly different from the one of the article, and in font size 16 (high prominence). In addition, the disclosure label was positioned either above the story’s title, at the beginning of the article on the right side of the text, or after the second paragraph directly inside the text.

Native advertising at the Guardian – © Screenshot

The participants in Wojdynski’s experiment had to read one of the 24 versions of the same online article and then answer a questionnaire. The results are sobering. Overall, more than two thirds (67.9%) of the participants were not able to identify the article as native advertising, despite the disclosure label. 14.6% even thought that the very label was a classic display advertisement. Only 17.5% of the participants recognised the article as an advertisement.

Wojdynski found only two characteristics which affect the recognition of advertising: Both the presence of the logo of the sponsor and a strong visual prominence of the disclosure label significantly helped users to identify a native ad as such. In addition, readers who were already familiar with native advertising were more likely to spot the sponsored article. Ultimately, Wojdynski showed that participants who identified the article as advertising perceived it as of lower quality and were less inclined to share it with other people.

Are We Able To Distinguish Native Ads from Journalistic Content?

David Hyman and his colleagues had a slightly different approach but tried to investigate the same question: Are people able to distinguish native ads from display ads and from free journalistic content?

They created a collection of 18 actual online stories, composed of eight native ads, one modified native ad, three classic advertisements and six unpaid free articles, originally published on various US platforms (The Atlantic, BuzzFeed, Facebook, Forbes, Gawker, Mashable, The New York Times, The Onion, and Vanity Fair). Participants had to click through all 18 examples and state whether they considered them as advertising/paid content or unpaid stories (with an “I don’t know” option for the undecided).

And again the results are startling. Almost half (49%) of the participants thought native ads were free content, 14% could not tell, and only 37% recognised them as such. Display ads, on the other hand, were easier to spot: 81% recognised them correctly, while only 19% were wrong or couldn’t decide.

Native Advertising Can Harm Journalistic Credibility

Both studies show once more that native advertising is an easy way to trick media users into consuming advertisements. It’s convenient for media organisations but even more for advertisers who can count on an even higher likelihood of their messages being read.

It’s a development which mostly harms the credibility of journalism and the media. When users constantly have to fear that they will tap into an advertising trap, they will only become more suspicious of an outlet’s integrity.

To fix this situation, media companies should become more sensitive towards this form of advertising. Quality media, in particular, should ponder more deeply the long-term consequences of this advertising strategy. A higher sense of responsibility would be sensible, too. Introducing a specific clause in their code of conduct, as well as measures to make native advertising more easily recognisable, are key steps towards ethical and transparent advertising.

Yet, maybe the solution lies not only with media outlets. Readers, too, should become more aware of native advertising – and only media journalism and increasing media literacy can make this happen.

This is an extended version of the original article, published in German in the Swiss magazine for advertising, marketing and media “Werbewoche” on January 16th, 2018.

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in The Digital News Dilemma: Scale And Advertising? Or Better Pay Models?

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter.

Tags: advertisement, Advertising, display advertising, Journalism, media, Media research, native advertising, Newspapers, Research