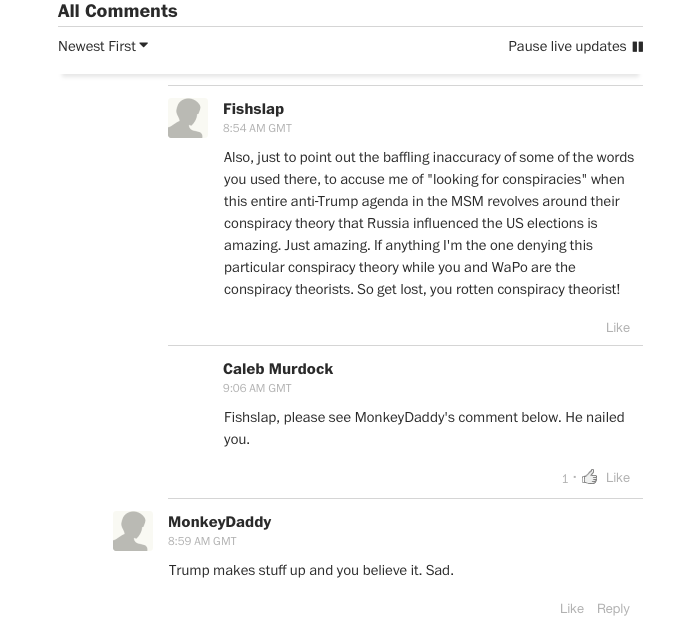

Readers debate online: Washington Post’s comments section, March 22 2017.

Online comments, still the most widely-used medium for audience participation and public engagement in mainstream news websites, continue to pose complex challenges to newsrooms.

Concern about the poor quality of comments – whether rudeness or hate speech – is often unmatched by resources to effectively manage participation.

Few newsrooms have reliable strategies to deal with readers’ comments. Over time media outlets have explored different moderation options by trial and error, including some radical alternatives, such as abandoning online news comments and/or moving them to Facebook-commenting.

Where newsrooms opt to keep reader comments, management strategies can take different approaches: ‘vigilant’ (where journalists “pre-moderate” or assess every comment before its publication); ‘loose’ (where the journalists only intervene in case of complaints by users); or more ‘decentralized/mixed’, which corresponds to a collaborative moderation, embedding users in the process.

Recent studies have examined a number of alternative approaches to comment moderation and reveal that attitudes are changing.

Journalists interact more with readers online

For one study, Normalising Online Comments, researchers Gina Chen and Paromita Pain interviewed 34 journalists about their views on reader comments. They found that journalists are becoming more comfortable with the practice and often engage with commenters to foster deliberative discussions or to quell incivility. This contrasts with earlier research that found journalists held negative attitudes towards online comments.

Chen and Pain, of the University of Texas School of Journalism, found that journalists are reasserting their public gate-keeping role, by moderating objectionable remarks and engaging with readers who contribute. In addition, the study suggests journalists are participating in “reciprocal journalism” by fostering mutually beneficial connections with the audience.

However, data also suggest some journalists still feel uncomfortable about engaging with commenters in this way, for fear it breaches the journalistic norm of objectivity.

A number of those interviewed expressed this uncertainty over their gatekeeping role: “I’m not the Facebook police” and “I’m not a First Amendment cop” – said two journalists explaining their resistance to intervene in what they perceive as a public and open space.

Polite interaction is more effective

Another study, by Marc Ziegele and Pablo B. Jost, of Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany, examined the various ways journalists interact with reader comments for their paper: Not funny? The effects of factual versus sarcastic journalistic responses to uncivil user comments.

The researchers conducted a web-based experiment aimed at developing realistic recommendations concerning the use of interactive journalistic moderation. The findings suggest that the presence of a journalist as moderator in the comments sections is not enough to stimulate a more constructive discussion.

While interactive moderation of uncivil comments can have positive effects, when the news outlet used sarcasm to expose an uncivil commenter’s behaviour as inappropriate, more damage was done than when the uncivil comment was left unmoderated.

On the contrary, whenever the news organisation responded to uncivil commenters in a factual and polite manner there was a perception of a more deliberative discussion atmosphere.

When readers moderate readers

A third study, conducted by myself, found that readers generally view online comments about news items very negatively. The study also found that when readers are invited to moderate comments by other readers, it can create undesirable power relationships among readers.

Readers of the Mail Online correct each other’s spelling and grammar, but such intervention can cause resentment.

Público, one of Portugal’s most prominent daily newspapers, decided to move to a collaborative moderation (where users moderate user comments) in 2012. Depending on how many points they gained or lost, users were classified as “beginners”, “influent”, “experienced” and ultimately “moderators”, sharing the moderation role with the community manager of the newspaper.

Before introducing this system in 2012, Público had a team of editors and journalists who assessed comments before publication. Before that, until March 2011, readers’ comments were automatically published without being moderated.

These experiments in moderation strategies are certainly not exclusive to Público, as newsrooms all over the world are trying to cope with the tension between freedom of expression and protection from abusive comments.

To assess the effectiveness of the collaborate moderation system and also to understand readers’ perspectives on comments, I closely examined a comment thread on a news article published in the press and online version of the newspaper on November 16th, 2013.

The article itself was about online comments, namely moderation practices. It provided a unique opportunity to examine readers’ viewpoints towards this discussion forum.

Readers favour editorial intervention over community moderation

Analysis of the 90 valid comments posted at the bottom of the article by readers revealed that most users addressed the “darker side” of online comments. Although accepting some positive aspects to comments (namely the extension of opinion pluralism and public debate, or added value to journalism), the majority of the readers discussed the negative aspects – particularly in regard to trolling and a commenter’s perceived desire to be in the limelight.

Aggressiveness, the violation of publication norms or the low quality of the posts in general were also raised as issues of concern by readers, the study revealed.

Reader “moderators” (readers that accumulate enough prestige points in order to manage other users’ comments) were also viewed with suspicion. Commenters described their behaviour as ‘arrogant’ and criticised them for arbitrary judgement and/or bad interpretation of publication norms.

Some participants even labeled the moderators’ management as “censorship” (using this word or associated words, such as ‘dictatorship’ or ‘blue pencil’).

It was interesting to note that some users in the comment thread studied implicitly proposed a more active and engaged role for the newspaper in the online news comments management.

Articles:

Ziegele, M.; Jost, P. B. (2016). “Not funny? The effects of factual versus sarcastic journalistic responses to uncivil user comments”. Communication Research, online first: 1-30.

Chen, G. M.; Pain, P. (2016). “Normalizing online comments”. Journalism Practice, online first: 1-17.

Marisa Torres da Silva (2016): “What do users have to say about online news comments? Readers’ accounts and expectations of public debate and online moderation: a case study”

You may also be interested in: Facebook launches campaign to end hate speech

Polite? Engaging? Are Journalists Moderating Their Approach To Online Comments?

March 22, 2017 • Ethics and Quality, Recent, Research • by Marisa Torres da Silva

Readers debate online: Washington Post’s comments section, March 22 2017.

Online comments, still the most widely-used medium for audience participation and public engagement in mainstream news websites, continue to pose complex challenges to newsrooms.

Concern about the poor quality of comments – whether rudeness or hate speech – is often unmatched by resources to effectively manage participation.

Few newsrooms have reliable strategies to deal with readers’ comments. Over time media outlets have explored different moderation options by trial and error, including some radical alternatives, such as abandoning online news comments and/or moving them to Facebook-commenting.

Where newsrooms opt to keep reader comments, management strategies can take different approaches: ‘vigilant’ (where journalists “pre-moderate” or assess every comment before its publication); ‘loose’ (where the journalists only intervene in case of complaints by users); or more ‘decentralized/mixed’, which corresponds to a collaborative moderation, embedding users in the process.

Recent studies have examined a number of alternative approaches to comment moderation and reveal that attitudes are changing.

Journalists interact more with readers online

For one study, Normalising Online Comments, researchers Gina Chen and Paromita Pain interviewed 34 journalists about their views on reader comments. They found that journalists are becoming more comfortable with the practice and often engage with commenters to foster deliberative discussions or to quell incivility. This contrasts with earlier research that found journalists held negative attitudes towards online comments.

Chen and Pain, of the University of Texas School of Journalism, found that journalists are reasserting their public gate-keeping role, by moderating objectionable remarks and engaging with readers who contribute. In addition, the study suggests journalists are participating in “reciprocal journalism” by fostering mutually beneficial connections with the audience.

However, data also suggest some journalists still feel uncomfortable about engaging with commenters in this way, for fear it breaches the journalistic norm of objectivity.

A number of those interviewed expressed this uncertainty over their gatekeeping role: “I’m not the Facebook police” and “I’m not a First Amendment cop” – said two journalists explaining their resistance to intervene in what they perceive as a public and open space.

Polite interaction is more effective

Another study, by Marc Ziegele and Pablo B. Jost, of Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany, examined the various ways journalists interact with reader comments for their paper: Not funny? The effects of factual versus sarcastic journalistic responses to uncivil user comments.

The researchers conducted a web-based experiment aimed at developing realistic recommendations concerning the use of interactive journalistic moderation. The findings suggest that the presence of a journalist as moderator in the comments sections is not enough to stimulate a more constructive discussion.

While interactive moderation of uncivil comments can have positive effects, when the news outlet used sarcasm to expose an uncivil commenter’s behaviour as inappropriate, more damage was done than when the uncivil comment was left unmoderated.

On the contrary, whenever the news organisation responded to uncivil commenters in a factual and polite manner there was a perception of a more deliberative discussion atmosphere.

When readers moderate readers

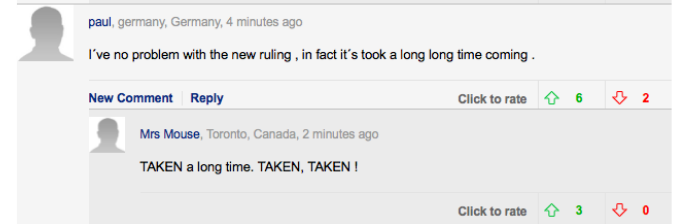

A third study, conducted by myself, found that readers generally view online comments about news items very negatively. The study also found that when readers are invited to moderate comments by other readers, it can create undesirable power relationships among readers.

Readers of the Mail Online correct each other’s spelling and grammar, but such intervention can cause resentment.

Público, one of Portugal’s most prominent daily newspapers, decided to move to a collaborative moderation (where users moderate user comments) in 2012. Depending on how many points they gained or lost, users were classified as “beginners”, “influent”, “experienced” and ultimately “moderators”, sharing the moderation role with the community manager of the newspaper.

Before introducing this system in 2012, Público had a team of editors and journalists who assessed comments before publication. Before that, until March 2011, readers’ comments were automatically published without being moderated.

These experiments in moderation strategies are certainly not exclusive to Público, as newsrooms all over the world are trying to cope with the tension between freedom of expression and protection from abusive comments.

To assess the effectiveness of the collaborate moderation system and also to understand readers’ perspectives on comments, I closely examined a comment thread on a news article published in the press and online version of the newspaper on November 16th, 2013.

The article itself was about online comments, namely moderation practices. It provided a unique opportunity to examine readers’ viewpoints towards this discussion forum.

Readers favour editorial intervention over community moderation

Analysis of the 90 valid comments posted at the bottom of the article by readers revealed that most users addressed the “darker side” of online comments. Although accepting some positive aspects to comments (namely the extension of opinion pluralism and public debate, or added value to journalism), the majority of the readers discussed the negative aspects – particularly in regard to trolling and a commenter’s perceived desire to be in the limelight.

Aggressiveness, the violation of publication norms or the low quality of the posts in general were also raised as issues of concern by readers, the study revealed.

Reader “moderators” (readers that accumulate enough prestige points in order to manage other users’ comments) were also viewed with suspicion. Commenters described their behaviour as ‘arrogant’ and criticised them for arbitrary judgement and/or bad interpretation of publication norms.

Some participants even labeled the moderators’ management as “censorship” (using this word or associated words, such as ‘dictatorship’ or ‘blue pencil’).

It was interesting to note that some users in the comment thread studied implicitly proposed a more active and engaged role for the newspaper in the online news comments management.

Articles:

Ziegele, M.; Jost, P. B. (2016). “Not funny? The effects of factual versus sarcastic journalistic responses to uncivil user comments”. Communication Research, online first: 1-30.

Chen, G. M.; Pain, P. (2016). “Normalizing online comments”. Journalism Practice, online first: 1-17.

Marisa Torres da Silva (2016): “What do users have to say about online news comments? Readers’ accounts and expectations of public debate and online moderation: a case study”

You may also be interested in: Facebook launches campaign to end hate speech

Tags: comments, Digital Media, digital news, Journalism, Journalism research, media, Media ethics, Media research, moderation, New York Times, Online News

About the Author

Marisa Torres da Silva

Related Posts

How a Swiss audience poll revealed strong reservations...

From ChatGPT to crime: how journalists are shaping...

Afghan media revolution: Reform journalism education or jeopardise...

The media revolution in Afghanistan

The new tool helping outlets measure the impact of investigative...

October 22, 2023

Audit of British Tory MP demonstrates the power of investigative...

September 13, 2023

The impact of competing tech regulations in the EU, US...

September 12, 2023

Enough ‘doomer’ news! How ‘solutions journalism’ can turn climate anxiety...

August 31, 2023

Student perspective: How Western media embraced TikTok to reach Gen...

August 19, 2023

Lessons from Spain: Why outlets need to unite to make...

July 26, 2023

INTERVIEW: Self-censorship and untold stories in Uganda

June 23, 2023

Student Perspective: Job insecurity at the root of poor mental...

June 9, 2023

The battle against disinformation and Russian propaganda in Central and...

June 1, 2023

Opinion: Why Poland’s rise on the Press Freedom Index is...

May 17, 2023

From ChatGPT to crime: how journalists are shaping the debate...

April 25, 2023

Student perspective: Supporting the journalists who face hopelessness, trauma and...

April 13, 2023

Interview: Why young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina feel they...

March 29, 2023

Humanitarian reporting: Why coverage of the Turkey and Syria earthquakes...

March 8, 2023

How women journalists in Burkina Faso are making a difference...

January 11, 2023

Dispelling the ‘green’ AI myth: the true environmental cost of...

December 29, 2022

New publication highlights the importance of the Black press in...

December 12, 2022

The enduring press freedom challenge: how Japan’s exclusive press clubs...

September 26, 2022

How Journalism is joining forces with AI to fight online...

September 14, 2022

How cash deals between big tech and Australian news outlets...

September 1, 2022

Panel debate: Should journalists be activists?

August 19, 2022

Review: The dynamics of disinformation in developing countries

August 9, 2022

Interview: Are social media platforms helping or hindering the mandate...

July 15, 2022

Policy brief from UNESCO recommends urgent interventions to protect quality...

July 5, 2022

EJO’s statement on Ukraine

February 28, 2022

Testing Large Language Models (LLMs) for disinformation analysis – what...

August 26, 2025

Recognising manipulative narratives: two perspectives on disinformation in Europe

August 22, 2025

What is a “good story” in times of war?

July 31, 2025

Perspectives of invasion: media framing of the Russian war in...

July 26, 2025

New elections in Romania: Coordinated online campaigns once again

July 24, 2025

The new tool helping outlets measure the impact of investigative...

October 22, 2023

Audit of British Tory MP demonstrates the power of investigative...

September 13, 2023

The impact of competing tech regulations in the EU, US...

September 12, 2023

Enough ‘doomer’ news! How ‘solutions journalism’ can turn climate anxiety...

August 31, 2023

Student perspective: How Western media embraced TikTok to reach Gen...

August 19, 2023

Lessons from Spain: Why outlets need to unite to make...

July 26, 2023

INTERVIEW: Self-censorship and untold stories in Uganda

June 23, 2023

Student Perspective: Job insecurity at the root of poor mental...

June 9, 2023

The battle against disinformation and Russian propaganda in Central and...

June 1, 2023

Opinion: Why Poland’s rise on the Press Freedom Index is...

May 17, 2023

From ChatGPT to crime: how journalists are shaping the debate...

April 25, 2023

Student perspective: Supporting the journalists who face hopelessness, trauma and...

April 13, 2023

Interview: Why young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina feel they...

March 29, 2023

Humanitarian reporting: Why coverage of the Turkey and Syria earthquakes...

March 8, 2023

How women journalists in Burkina Faso are making a difference...

January 11, 2023

Dispelling the ‘green’ AI myth: the true environmental cost of...

December 29, 2022

New publication highlights the importance of the Black press in...

December 12, 2022

The enduring press freedom challenge: how Japan’s exclusive press clubs...

September 26, 2022

How Journalism is joining forces with AI to fight online...

September 14, 2022

How cash deals between big tech and Australian news outlets...

September 1, 2022

Panel debate: Should journalists be activists?

August 19, 2022

Review: The dynamics of disinformation in developing countries

August 9, 2022

Interview: Are social media platforms helping or hindering the mandate...

July 15, 2022

Policy brief from UNESCO recommends urgent interventions to protect quality...

July 5, 2022

EJO’s statement on Ukraine

February 28, 2022

13 Things Newspapers Can Learn From Buzzfeed

April 10, 2015

How Data Journalism Is Taught In Europe

January 19, 2016

Why Journalism Needs Scientists (Now)

May 13, 2017

Digitalisation: Changing The Relationship Between Public Relations And Journalism

August 6, 2015

The Lemon Dealers

June 27, 2007

The new tool helping outlets measure the impact of investigative...

October 22, 2023

Audit of British Tory MP demonstrates the power of investigative...

September 13, 2023

The impact of competing tech regulations in the EU, US...

September 12, 2023

Enough ‘doomer’ news! How ‘solutions journalism’ can turn climate anxiety...

August 31, 2023

Student perspective: How Western media embraced TikTok to reach Gen...

August 19, 2023

Lessons from Spain: Why outlets need to unite to make...

July 26, 2023

INTERVIEW: Self-censorship and untold stories in Uganda

June 23, 2023

Student Perspective: Job insecurity at the root of poor mental...

June 9, 2023

The battle against disinformation and Russian propaganda in Central and...

June 1, 2023

Opinion: Why Poland’s rise on the Press Freedom Index is...

May 17, 2023

From ChatGPT to crime: how journalists are shaping the debate...

April 25, 2023

Student perspective: Supporting the journalists who face hopelessness, trauma and...

April 13, 2023

Interview: Why young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina feel they...

March 29, 2023

Humanitarian reporting: Why coverage of the Turkey and Syria earthquakes...

March 8, 2023

How women journalists in Burkina Faso are making a difference...

January 11, 2023

Dispelling the ‘green’ AI myth: the true environmental cost of...

December 29, 2022

New publication highlights the importance of the Black press in...

December 12, 2022

The enduring press freedom challenge: how Japan’s exclusive press clubs...

September 26, 2022

How Journalism is joining forces with AI to fight online...

September 14, 2022

How cash deals between big tech and Australian news outlets...

September 1, 2022

Panel debate: Should journalists be activists?

August 19, 2022

Review: The dynamics of disinformation in developing countries

August 9, 2022

Interview: Are social media platforms helping or hindering the mandate...

July 15, 2022

Policy brief from UNESCO recommends urgent interventions to protect quality...

July 5, 2022

EJO’s statement on Ukraine

February 28, 2022

Reporting War, Journalism in Wartime

February 1, 2005

Has Journalism Been Let Down By The EU?

March 28, 2017

Survival strategy

March 5, 2004

Turkey: 100 Media Outlets Closed, 30 Journalists Detained

August 5, 2016

Two “magic recipes” for more journalistic quality

April 16, 2004

Operated by

Funded by

Newsletter

Find us on Facebook

Archives

Links