To what extent is media pluralism – described in the latest Media Pluralism Monitor report (MPM2020) as “one of the essential pillars of democracy” – crumbling throughout Europe? Roman Winkelhahn summarises the conclusions reached by a team of researchers at the European University Institute.

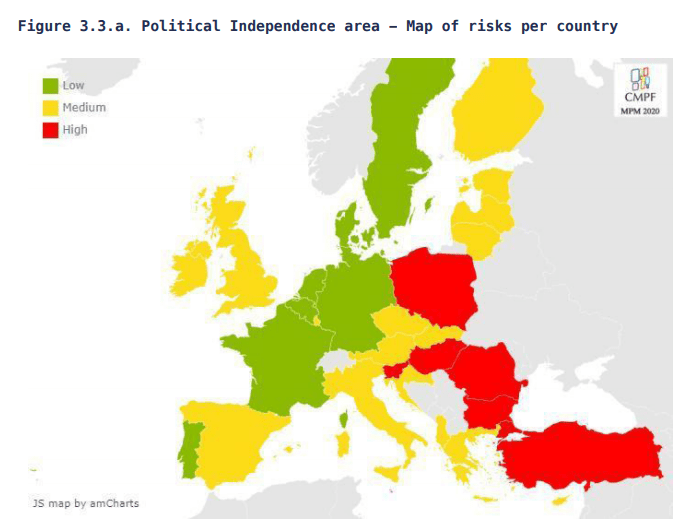

In Turkey and several Eastern European countries, the media are under particular threat of political interference.

MPM2020 covers the years 2018 and 2019 and assesses the state of media pluralism in Albania and Turkey as well as in the member states of the European Union (which then still included the UK). None of the 30 countries covered can be said to have emerged from the study with a completely unblemished record. An ideal degree of media pluralism still seems likely to remain unattainable in most countries for as long as the media industry continues to be vulnerable to commercial and political pressures, especially in view of the additional risks posed by the digital transformation of the industry.

The research team, based at the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) at the Robert Schuman Center at the European University Institute in Florence, measured media pluralism under four main headings: basic protection (which includes regulatory mechanisms, the status of journalists and access to the Internet) plus market plurality, political independence and social inclusiveness.

Economic vulnerability

In general, the area of market plurality is the one in which the researchers identified the greatest threat to media pluralism in Europe. They gave this a risk score of 64%, which they note is “considerably higher” than the corresponding score given in the Media Pluralism Monitor report for 2017 (MPM2017), when the risk was deemed to be 53%. They attribute the increase to ever higher levels of news media concentration, less transparency with regard to ownership and reduced economic sustainability. None of the 30 countries surveyed was found to be low risk (scoring less than 33%) in the “market plurality” category, and the research team sees this as being indicative of the increasing economic vulnerability of the media.

Male experts are more often invited to comment on political programmes and articles than are female experts. MPM2020

In 28 countries (all but Albania and Estonia), women tend to be under-represented in news and current affairs broadcasting, or are largely depicted in a stereotyped way. In all countries, the majority of the experts invited to appear on political programmes are men.

Horizontal media concentration

Only four countries (France, Germany, Greece and Turkey) show a medium risk in the context of horizontal media concentration (i.e. the concentration of media ownership within a given sector – press, audio-visual, etc.). The media markets of all the other countries surveyed are highly susceptible to this phenomenon. The risk is especially pronounced in the audiovisual sector, where there are not enough media outlets operating to guarantee market pluralism. In the online sector, there is inadequate competition between online platforms in at least 23 countries, and market concentration was identified as a risk factor in all 30 countries surveyed.

Among the news media sectors, the most vulnerable are newspapers and local media industries. MPM2020

This trend goes hand in hand with the often-invoked existential threat faced by newspapers and local media. In a section devoted to “Media viability”, the researchers note that these two sectors are particularly at risk. For newspapers, the Europe-wide risk score is 80%, while for local media it is 76%. MPM2020 emphasises the vital contribution made by local media to the democratic process, which historically have played an important role in “informing small communities, fostering their democratic participation, and monitoring the local powers.”

Political influence and editorial autonomy

The report writers note that the media in Eastern European countries and Turkey in particular are hampered by the constant threat of political interference and attempts by politicians to dictate the news agenda. The ability of journalists to exercise editorial independence is circumscribed by the fact that in these countries politicians are able to influence the appointments of editorial and publishing directors, and also because in many countries the legal structure does not allow for effective self-regulation.

PSM systems are usually established by the state, which, in some cases, still maintain influence over them. MPM2020

One risk that is apparent in all the countries surveyed arises from the lack of regulation in the field of political advertising, especially in the online sector. Here the risk score is 65%. Even countries such as Germany and Denmark, which do well in many other areas, perform badly in this respect. This is mainly due to a lack of transparency and the difficulty of monitoring financial transactions between political actors and online providers.

Digital context heightens risk

Operating in a digital context clearly accentuates the risk level in all areas except one. “With the exception of the Market Plurality area, the risk scores of the digital component of each area are, in general and on average, higher than the overall score in that area,” the report says. This is mainly due to the lack of control and transparency when it comes to online platforms, and the unsatisfactory way in people – especially minorities – are dealt with on the Internet. In particular, MPM2020 highlights the inadequate handling of the issue of hate speech against vulnerable social groups online.

Action points

In addition to calling for governments to “proactively protect” freedom of expression, the report authors call for uniform standards to be applied across Europe in the area of media self-regulation. They also call for the European Union to take the lead in safeguarding media independence.

The study also recommends that regulatory incentives be applied to media markets to help ensure the survival of smaller media. However, it points out that care needs to be taken when implementing such measures, to avoid the possibility of governments exerting undue influence.

A kind of digital service tax (DST) could also be used to foster media plurality: “by reducing the disparity in the fiscal burden between industries which are players in the same market; and by earmarking a part of the DST’s revenue to support media pluralism”.

As a way of addressing the lack of diversity in editorial offices and among the news media audience, the research team recommends not only a “gender equality policy” but also the active involvement of minorities and more joined-up support for community media.

The study paints a rather gloomy picture of the European media landscape. One can only hope that the next Media Pluralism Monitor will not be even gloomier, as the long-term consequences of the coronavirus crisis – both for the financial underpinning of the media and for media freedom – will by then in all likelihood be all too apparent.

The Media Pluralism Monitor 2020 is available on the website of the European University Institute.

This is a slightly abbreviated version of an article that originally appeared in German on EJO’s German-language site. It is also available in French on EJO’s French-language site.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO.

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in “Do as I say, not as I do. Media and Accountability“

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Image: MPM2020 (screenshot)

Tags: digital environment, Europe, European Union, media diversity, Media Pluralism, Media Pluralism Monitor, Media regulation, MPM2020