Migrants in a park outside the railway station in the northern Italian city of Como in the summer of 2016. Many migrants who were then trying to reach Northern Europe via Switzerland became stranded in Como after the Swiss authorities closed the border to them.

In the five years since the European refugee crisis began, controversies related to migration have deeply affected political landscapes across the EU, yet no “European solutions” have so far been found. A new study by the European Journalism Observatory (EJO) now shines a light on the media’s role in the migration debate.

EJO’s comparative analysis reveals that in each country, the media tell different stories about migrants and refugees. Clear differences in the quantity and quality of coverage can be discerned not only between Western and Central Eastern Europe, but even within Western Europe. The study also reveals a number of blind spots in the coverage of migration.

For this research project, a dozen EJO partners analyzed media coverage of migrants and refugees in 17 countries. The study is based on 2,417 articles published during six separate weeks selected between August 2015 and March 2018. It is the first international project to compare the coverage of migrants and refugees across so many different political systems, media systems and journalistic cultures. Further details and the full report (in both German and English) are available on the website of the Otto Brenner Foundation, which co-funded the study.

A specific German perspective

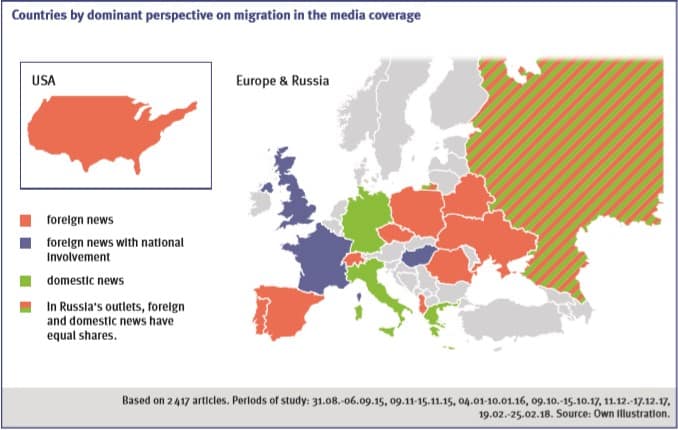

In many parts of Europe, migration is seen mainly as a foreign affairs issue.

Germany, which currently provides a home to 1.1m refugees (according to UNHCR data for 2019), emerged from the European refugee crisis as one of the world’s top five host countries for refugees, along with Uganda, Pakistan, Turkey and Sudan. Our research found that this unique position has resulted in a specific German perspective on the issue. The sheer quantity of coverage in Germany far outstrips that of almost all other countries in the study – and is only paralleled by Hungary, whose prime minister Viktor Orbán has positioned himself as an opponent of German chancellor Angela Merkel with regard to asylum policy.

The study also reveals fundamentally different patterns of coverage between Germany, Italy and Greece and all the other EU countries in our sample. In Germany, Italy and Greece, migrants and refugees are presented as domestic topics, reflecting the fact that these countries tend to be the main destinations of migrants and refugees. However, the media in all other EU countries in our sample treat the topic primarily as a foreign affairs issue – events related to migration take place far away from home, outside the domestic borders. Media in France, the UK and Hungary emphasize the prominent role of their leaders in international policy-making. Germans might be surprised to learn that there seems to be little public pressure in other countries to find a “European solution” to the regulation of asylum procedures.

A question of attitude

The study also finds stark differences in the tone of coverage in different countries. In general, media in Central and Eastern Europe focus more on problems experienced with, and protests against, migrants and refugees. Media in Western European emphasize the situation of migrants and refugees, and the help provided to them. Western European media in our sample also quoted many more (non-migrant) speakers with positive attitudes towards migrants and refugees than media in Central and Eastern Europe. A pattern also emerges when we contrast data for left-liberal media and media with a more conservative profile: liberal-left media quoted more speakers with a positive attitude, and reported considerably more on help for and the situation of migrants and refugees.

Media also report on immigration from different parts of the world. Africa is the main point of reference in Italy and to some extent in France. While all other countries in Western Europe focus on immigration from the Middle East, the Italian newspaper La Stampa did not publish a single article focusing on migrants or refugees from the Middle East. For media in Russia, Poland, Belarus and Ukraine, migration and refugee flows from Ukraine were also an important theme.

Refugee or migrant?

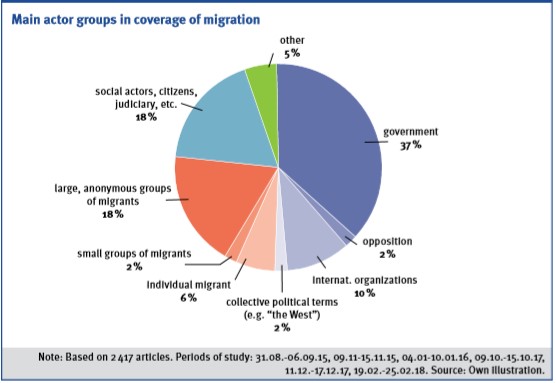

One of the main problems identified in our study is that media across Europe do not make clear to their audiences the background and legal status of people seeking to enter Europe as a migrant or refugee. Coverage is dominated by political debates and political actors (45%), leaving almost no room (4% of the articles) for coverage of economic, cultural, historic and other background information.

Only a third of the articles (33%) make clear the distinction between refugees, who have a protected legal status, and migrants, who leave their countries of origin for economic, social, educational and other reasons. Most articles (60%) confuse migrants and refugees or remain unclear. Do they do this out of ignorance? Because national politicians use ambiguous wording? Because journalists assume their audiences don’t know the difference – or because they lack the time and space to be more specific? The answers to these questions lie beyond the scope of the current study.

The media are also vague on the question of where migrants and refugees come from. Only 778 out of the 2,417 articles retrieved for the study weeks specify countries of origin – 293 articles mention Syria, the others “Africa” (64), Myanmar (30), Albania and Ukraine (18 each), and Afghanistan (16). But over time, some changes can be observed: in the earlier weeks selected for analysis, the Middle East was regularly mentioned as a place of origin, and in cases where individuals were identified, they were mostly described as “refugees”. In the later weeks surveyed, we increasingly find people identified as “migrants”. However, the share of articles that do not identify the people presented as either refugees or migrants remains high throughout our period of analysis.

Silent bystanders

The media rarely focus on refugees or migrants as individuals.

Asking migrants and refugees about their background and motives might help, but migrants and refugees tend to be the silent bystanders of migration coverage. While 26.6% of articles do feature migrants and refugees as main actors, 18% cover them only as large, anonymous groups. A mere 8% of the articles feature migrants and refugees as individuals or families, while citizens and civil society actors in destination countries are the main actors in 18% of the articles.

Very few migrants and refugees featured in the articles are actually quoted: the media quoted 411 migrant speakers, compared to 4,267 non-migrant speakers. Although helpers tend to be individualised, those at the receiving end of help are not. As found in previous studies, coverage also over-represents male (and also underage) migrants and refugees at the expense of adult females.

Giving voice to the voiceless

With regard to the representation of migrants and refugees, the European media could learn something from the United States, which formed part of our sample as well. While the Washington Post focused mainly on immigration from Central America in the study period, the New York Times took more of a global perspective and focused on the “European refugee crisis”. US articles featured a particularly high number of individual migrants and refugees, who were also quoted – probably as a result of Anglo-Saxon reporting traditions and a code of ethics (formulated by the Society of Professional Journalists) that says journalists should seek to “give voice to the voiceless”. Within Europe, the Spanish media come closest to this degree of interest in the perspective of migrants and refugees.

However, the study also shows that public debate around the issue in other countries is often far from being as one-sided as is often assumed. We also compared the percentage of speakers quoted who had positive attitudes towards migrants and refugees with the percentage of speakers quoted who had negative attitudes. In almost all the countries covered by this study, the two media outlets in our sample offered contrasting positions. We conclude from these results that more diverse – or at least less black and white – approaches towards migration issues can be found in the media of each country.

The Hungarian media, for example, offer a more varied picture than one might expect. Magyar Hírlap, closely aligned with the Orbán government, does not quote a single migrant or refugee in its articles in all six study weeks. But on the independent news portal Index.hu, the situation of migrants and refugees receives more attention, and at least some migrant speakers are quoted.

- Susanne Fengler and Marcus Kreutler: “Migration coverage in Europe’s media – A comparative analysis of coverage in 17 countries”, OBS-Working paper 39, Frankfurt am Main, January 2020

Main image: Mattia Vacca (reproduced with permission) / Infographics from the EJO report

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in How Europe’s Newspapers Reported the Migration Crisis

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter

Tags: a voice to the voiceless, Anglo-Saxon reporting traditions, European refugee crisis, European Union, individualisation, legal status, migration coverage, refugee or migrant