© Raluca Radu

This is the second part of a two part study, comparing Europe’s Public Service Media (PSM). In a first article on the subject, we found that PSM’s budgets vary enormously across Europe and organisations do not share a common financial or organisational strategy.

Every European country has public service media, but there are huge variations in their reach, resources and impact. Some enjoy more than 55 percent market share (public radio in Switzerland) or more than 70 percent of public trust (Latvia), yet in Romania public service television struggles to reach five percent of audiences, while in Poland political pressure threatens the independence and future of the national broadcaster.

The European Journalism Observatory (EJO) compared PSM in nine European countries (Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Switzerland and United Kingdom). Ukraine’s new public broadcaster was also studied but, as it was established only in 2017, it was not included in the comparison

Main findings:

The study found that political and economic pressures influence professional performance and market share of PSM, but that their impact varies widely across the region.

- In Switzerland, Germany and the United Kingdom, public service media have a strong position in the national audiovisual market, reaching, in some cases, more than half of the audiences.

- In Ukraine, Romania, Portugal and Italy, strong competition means either public television or public radio have less than 20 percent of market share.

- Public financial support comes with responsibility and accountability demands from audiences, politicians and the government.

All public media organisations are under pressure to maintain high professional standards, but also to reach large audiences – both to justify the amounts received from audio-visual licence fees or public budgets, but also to ensure they remain relevant

A Definition of Public Service Media

The term public service media is used here as it best reflects that most public media organisations now operate on multiple platforms, however it is noted that most are still dominated by their broadcasting legacy.

PSM in some of the countries studied consists of television, radio and associated digital platforms (such as websites, dedicated YouTube channels and dedicated pages on social media). Other national public broadcast organisations include a press agency, also funded from the state budget. The EJO study is limited to television and radio broadcasters and their related internet presence.

The European Broadcasting Union lists universality as the most important attribute of a PSM, followed by independence, excellence, diversity, accountability and innovation. There is also a difference between a state-owned media and a public service media in terms of their scope, credibility and public remit.

Market Share

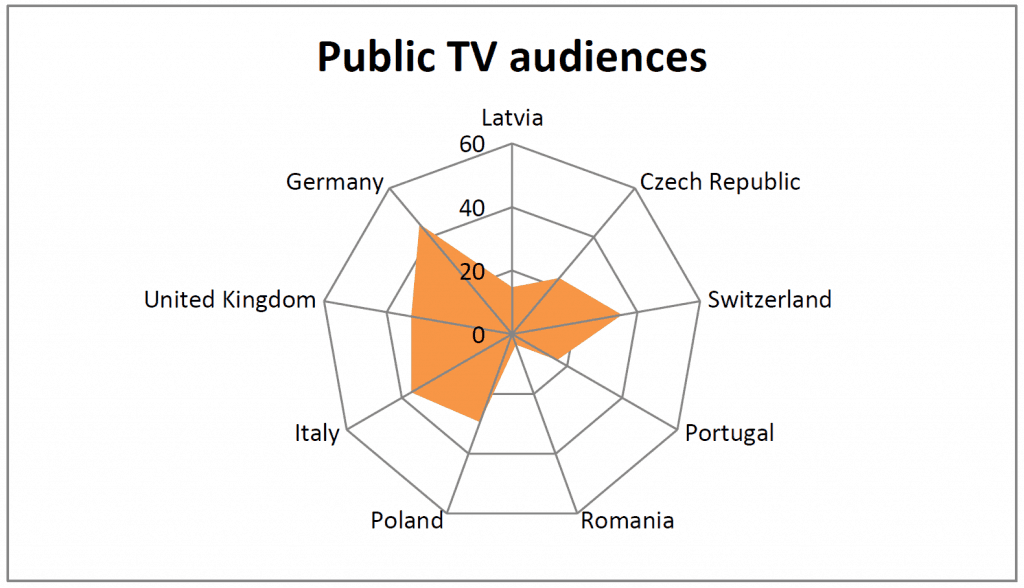

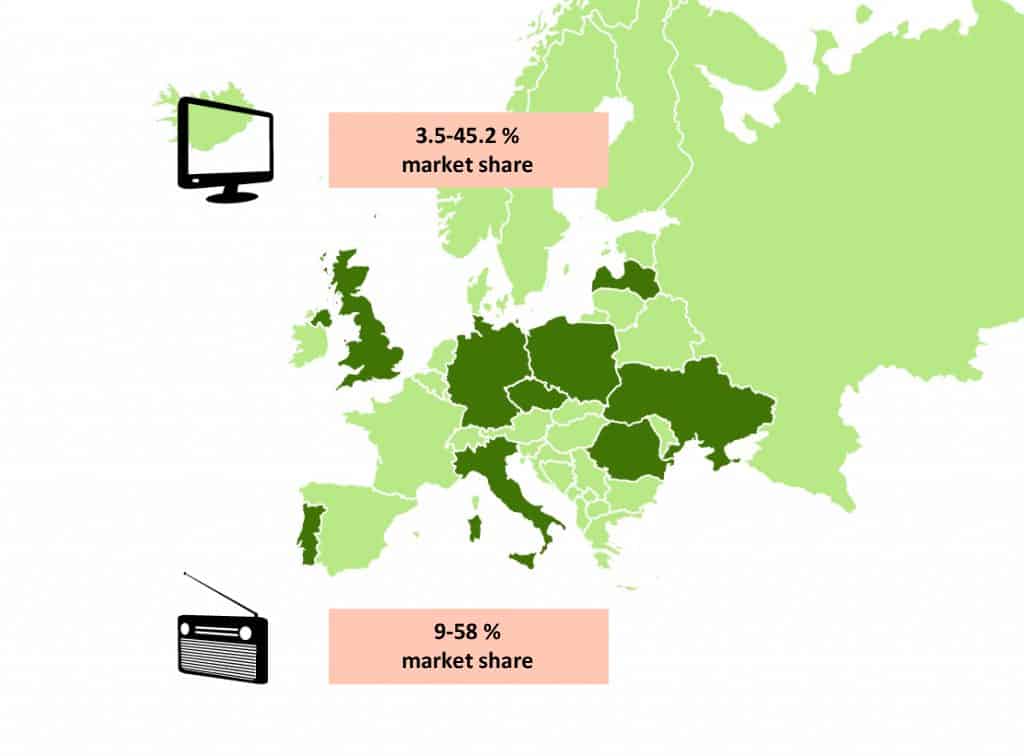

Data shows that, in general, a large market and a well-financed PSM (see the first EJO analysis) correlate with a large market share. In the UK, Germany, Italy and Switzerland, public television channels control between one third and two thirds of the market.

The German public TV channels reach altogether around 45 percent of the market (in 2016), while the two main public broadcasters ARD and ZDF reach 12 and 13 percent respectively. ARD’s 9 regional programmes have a market share of around 12 percent. Czech and the Polish television, with competition from media products of publicly owned companies (Central Media Enterprises and Modern Times Group, in the Czech Republic; Scripps Networks Interactive and Cyfrowy Polsat in Poland), reach approximately between 23 and 29 percent of the market. Latvian and Portuguese PSM reach even smaller audiences: between 15 and 16 percent, respectively.

With a historical low of 3.5 percent market share in 2016, Romanian television, TVR, appears the least relevant public service broadcaster in our sample of established PSM (see Fig. 1). The market share is low due to intense competition and a severe austerity policy. To lower TVR’s debt, all production funding was cut – except for news programmes. To regain audiences TVR experimented with pundit based talk-shows, popular on all-news televisions in Romania and elsewhere. But copying others did not pay off for Romania’s public broadcaster and by the end of 2017 TVR’s market share has not increased.

Fig. 1. Public TV market shares range from about 45% in Germany to 3.5 in Romania. Sources: KEK – Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich, Germany, 2016; BBC, United Kingdom, 2016; RAI, Italy, 2016; SRGSSR, Switzerland, 2016; TVP, Poland, 2016; ČT, 2015; RTP, Portugal, 2017; TVR, Romania, 2016; LTV, Latvia, 2016.

Public service radio

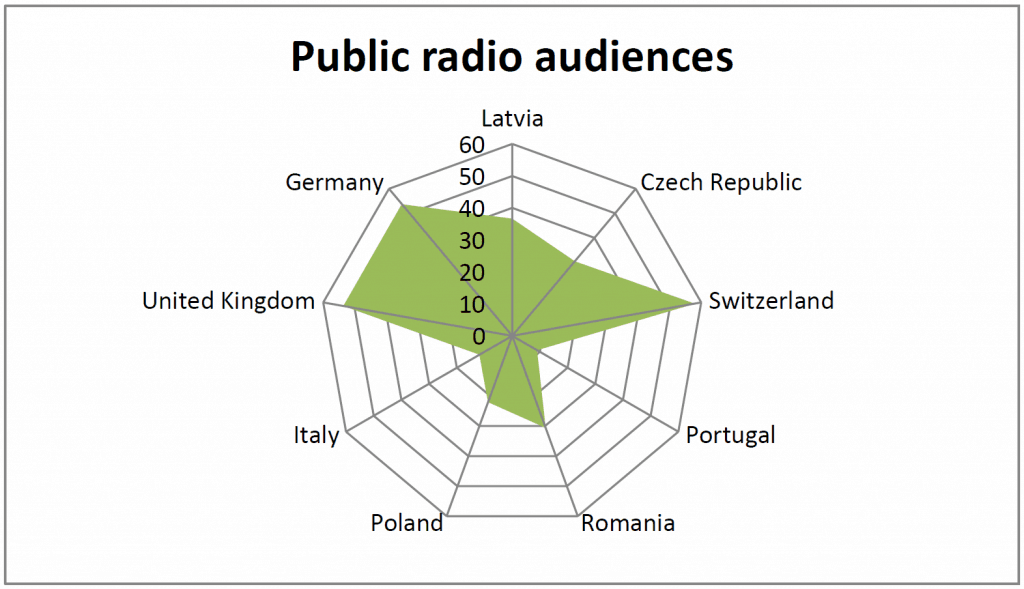

Public service radio in UK, Germany and Switzerland have an even more dominant position, with over 50 percent of the market share. This likely to be due to better access to financial resources, as shown in the earlier EJO study.

Public radio stations, with a larger staff and better access to funding, tend to be the strongest in most of the markets studied: Czech, Romanian and Latvian radio have between 30 and 35 percent of market share, while Polskie Radio has about 20 percent.

PSM radio seems to have the toughest competition in southern Europe: In Portugal and Italy public radio reaches only about 10 percent of the audience.

Fig. 2. The public radio has more than half of the market in three countries: Switzerland, United Kingdom and Germany. Sources: Media Analyse, Germany, 2016; BBC, United Kingdom, 2015; RAI, Italy, 2016; SRGSSR, Switzerland, 2016; PR, Poland, 2016; ČRo, 2015; RTP, Portugal, Dec 2016; SRR, Romania, 2016; LR, Latvia, Spring 2017.

Antitrust regulations in the European Union indicate that “if a company has a market share of less than 40 percent, it is unlikely to be dominant”, Romania’s audio-visual legislation lowers the threshold to as little as 30 percent.

In Switzerland, the PSM, SRG SSR may lose some of its audience during the day, to more interesting offers from across the border, in German, French and Italian. In Italian-speaking Switzerland, the radio stations of SRG SSR have a market share of 74 percent, in the other two parts of the country it’s around 64 percent. The TV market share is much lower. However, the public comes back to SRG SSR for national news in prime time. With around 31 percent of the TV market share and more than 55 percent of the radio market share, there is little doubt which newsrooms have dominant voices in Switzerland.

In other European countries, very strong public service media would raise concerns about possible political influence over news content. However, this is currently not the case in Switzerland. Political decision-making, concentrated on small cantons and based on direct democracy, has allowed for a strong professional journalistic consciousness to develop (as Radu, 2016 shows).

Politics, accountability and the PSM

Usually in Europe, accountability mechanisms are institutionalised, in the form of a national broadcasting or audio-visual council, which grants licenses and supervises the adherence to AV regulations, as the Audiovisual Media Services Directive of the European Union stipulates. Public Service Media boards are answerable to Parliament.

Nevertheless, national legislation may allow political parties to interfere and to try to control PSM content, by appointing members of national broadcasting councils, members of the PSM boards of directors, or by other, less obvious means, such as budgetary allocations and (threats of) legislative changes.

Highly Trusted Public Service Media

In Latvia, PSM are supervised by an independent authority of five members, chosen from among professionally or academically experienced candidates suggested by specialised non-governmental organisations in the fields of media, human rights, culture, education and science. In practice, they are elected by Parliament according to the political proportionality of the governing coalition. The authority may function as a buffer against the pressure of narrow political and commercial interests, but their independence is not guaranteed. Latvian PSM are financed directly from the state budget, depending on political decisions. To date, Latvian PSM remain under-financed even in comparison to neighbouring Estonian and Lithuanian PSM. Despite the obvious difficulties, audience polls show growing public trust in PSM: in 2015, 74 percent said they trusted LTV, while LR enjoyed even more credibility, reaching 84 percent.

Portuguese PSM also rank high when it comes to public trust, with a support of about 60 percent of the population. An explanation may lie in the composition of the independent general board (Independent General Council, CGI), which supervises the implementation of the contract between the Government and RTP (Rádio e Televisão de Portugal, Portugal’s public service broadcasting organisation). Of the six members, two are chosen by the government, two by the Opinion Council of RTP and two are co-opted by the previous four and have to be personalities with recognised value in media and management landscapes. The board of administration is directly nominated by the government, but financial support comes from license fees and advertising.

The BBC has an extraordinary reputation with the British public and sets the standards for PSM worldwide. British public service media is governed by the BBC Board, that establishes the strategic director and sets the budget, and is regulated by the Office of Communications (Ofcom). Trustworthiness scores are very high: in 2016, 89% of all those who watch at least one PSB channel said that the PSM ‘news programmes are trustworthy… [for] informing our understanding of the world’ (Ofcom). Until now, there have been no serious cases where this independence has been breached by politics, or by business.

Swiss public service media is unique as it is provided in three languages (TV)/ four languages (radio). This is intended to contribute significantly to integration in the multicultural country. All language channels enjoy comparably high trustworthiness, as shown by recent research, due to the absence of political interference and a highly developed public service culture. Yet, there are also parties which oppose PSM in Switzerland. The populist right (SVP, Lega Ticinese) recently challenged public service media, although the “No Billag” movement, which wanted to abolish the country’s audio-visual license fees, was defeated in a recent referendum.

Politically Challenged Public Service Media

In Germany, the public service broadcasters are governed by broadcasting councils. However, in 2014, growing concerns over the perceived influence of political parties on ZDF led to a ruling by Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court aimed at strengthening the public service broadcaster’s independence from the state. The court ruled that state representatives must not exceed one third of the total membership in each of ZDF’s two supervisory bodies. Representatives of civil society must reflect relevant social groups, taking into account minorities and diverse perspectives. These arrangements, which are uncommon in Europe, did not stop accusations by anti-immigrant activists that the country’s public service media belonged to the so-called “lying press” (Lügenpresse).

The Council of Czech Radio and the Council of Czech Television are appointed and removed by the Prime Minister at the proposal of the Chamber of Deputies. The appointment procedures have been criticised for being too dependent on political power. The members of the Council are not always effectively independent. The 2005 Television Across Europe Study stated that the composition of the Council reflects the distribution of power within the Chamber of Deputies. This continues to be a problem, since the procedure has not changed since that time. Some members of the Council are members of political parties or have close relationships with them.

In Romania, the majority of the boards of the two PSM are appointed by the Parliament, depending on the political configuration; the Presidency and the Government appoint one member each; there is also an employee representative and one for the minorities’ parliamentary group. SRR and SRTv are bound by law to provide fair and balanced information, to educate, to inform and to entertain the public. Underfinancing and strong political ties make reaching these ideals a difficult task.

In Italy, RAI is entirely controlled by the State through the Economy Ministry. It owns 99.56 percent of the share capital (0.44 percent is owned by SIAE, the Italian copyright collecting agency). RAI answers to the Parliamentary Commission, which also appoints the majority of the board. This very strong political influence has long been a problem for RAI. Particularly in the past, the main news channels (TG1, TG2, TG3) reflected the views of specific political parties, a situation described in detail by the scientific literature on the phenomenon of Berlusconization (after the former Italian PM).

Polish PSM is even more politically influenced. Since July 2016, the five member PSM supervisory body has been the National Broadcasting Council, with three members elected by Parliament and two by the President. Now, this arrangement gives the ruling party PiS majority the chance to influence the senior management. International institutions and journalistic associations regularly complain about the biased reporting of national politics. The ongoing parliamentary crisis has shown huge differences in the way PSM reports on current political events – in comparison to commercial media outlets. The public broadcaster appears to be answerable to political actors, rather than the public. However, the public itself is divided – with some audiences declaring themselves satisfied with the current situation.

In January 2017, the National Public Broadcasting Company of Ukraine was officially launched. The date marks a transition from a state owned audiovisual service to a public media service. The transition is supported by a Council of Europe Project, with financial help from 16 European contributors, the European Union, as well as Norway, Switzerland and Turkey. Currently, Ukrainian Public Broadcasting faces the challenges of a lack of funding, a huge debt inherited from its predecessor, and authorities’ reluctance to accept the idea of public broadcasting. Its unique position as a very young PSM makes it harder to compare to other PSM in our sample.

The future of public service media

Highly trusted or not, Europe’s public service media are constantly in the centre of discussions concerning the position of public media in modern society, political ties and trustworthiness, market share, financing, innovation and social responsibility.

By obeying high standards of professional conduct and keeping a relevant position in the media market, Europe’s PSM should face few problems increasing their credibility and protecting their legitimacy. Without strong, independent and creative public service media – offering a civilised public sphere, European culture and democracy could have a difficult future.

*This article has been corrected on April 11th, 2018, as the original version contained incorrect numbers and figures.

This is the second part of a two part study, comparing Europe’s PSM. Part 1, on Europe’s public service financial strategies, can be found here.

With Tina Bettels Schwabbauer, Ainars Dimants, Michał Kuś, Caroline Lees, Ana Pinto Martinho, Antonia Matei, Stephan Russ-Mohl, Massimo Scaglioni, Sandra Stefanikova, Adam Szynol and Halyna Budivska.

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter.

Tags: ARD, BBC, Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Latvia, licence fee, media independence, PiS, Poland, PSB, PSM, public service broadcasting, public service media, Rai, Research, Switzerland, Ukraine, ZDF