Iran has been one of the countries hardest hit by the novel coronavirus. The Islamic Republic’s response to the outbreak has been controversial. The media’s coverage of the crisis has been limited to publishing the official narrative. However, the lack of independent investigation and fact-checking has inflamed distrust in the Iranian media.

Iran has been one of the countries hardest hit by the novel coronavirus. The Islamic Republic’s response to the outbreak has been controversial. The media’s coverage of the crisis has been limited to publishing the official narrative. However, the lack of independent investigation and fact-checking has inflamed distrust in the Iranian media.

Furthermore, the country’s leadership and the state-run media stand accused of trying to cover up the extent of the Covid-19 outbreak in Iran. They have also been touting conspiracy theories that the virus could have originated as a US-produced bioweapon.

The Iranian media’s response to the outbreak is a byproduct of the state’s tight control of the media. Almost all news outlets in Iran are either run by the state or have ties to the establishment. The sole provider of radio and television services in the country is the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) corporation, which is under the direct control of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. All news agencies are directly run by different arms of the system, and private outlets rely on government support to sustain their operations. For instance, newspapers depend on subsidised paper imports which are allocated by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.

There is an ever-growing list of official and implied red lines. Crossing such lines can trigger harsh reprimands for journalists and their outlets. It is therefore not surprising that the Iranian media have toed the line and stuck to the official narrative regarding the Covid-19 outbreak.

Turning a blind eye

The authorities denied the existence of the disease in Iran until the first fatalities were officially confirmed on 19 February 2020. The health ministry has since held daily press briefings to announce the latest data on the number of infections and mortalities attributed to Covid-19 in Iran. The reliability of the statistics has been questioned by citizens, independent journalists and foreign media. Among the most notable examples of such critiques are a Washington Post report including satellite images of burial sites (12 March) and a New York Times article on Iran’s coronavirus reporting (28 February).

Iranian health officials have on several occasions indicated that the real tally of coronavirus infections and deaths is higher than the official figures. Rick Brennan, an emergency director for the World Health Organization who recently visited Iran, told Reuters on 17 March that the true Covid-19 toll may be five times higher than the official numbers. Despite the backdrop, to date not a single Iranian media outlet has launched an independent investigation into the matter.

Some Iranian political figures, including members of parliament, have censured the government for downplaying the extent of the outbreak. Some Iranian outlets ignored the allegations while others published them without verification or additional reporting.

Following the outbreak, privately owned papers mainly published rehashes of the official narratives peppered with mild criticism. The criticism has been mostly directed at President Hassan Rouhani’s administration and municipal administrators, not at the Islamic Republic’s overall response to the outbreak. The Persian daily Donya-e-Eqtesad ran a story on 1 March describing how air pollution could aggravate the health risks associated with Covid-19. The piece criticised the Tehran Municipality for failing to reduce air pollution.

All major newspapers in Iran were closed between 18 March and 3 April for the Nowruz holidays, reducing the breadth of coverage of the outbreak, which during this period was confined almost exclusively to the national broadcaster and state-run news agencies.

Criticism from hardliners

Once the outbreak had been officially confirmed, Iranian conservatives began criticising the government on social media. Commenting via Twitter on 30 March, former Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commander and MP-elect Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf accused the administration of “ignoring reality” and “unjustified optimism”. He tweeted that Rouhani had “…worsened the crisis, then asked for help and put the blame on others”. Mehr News Agency published the tweets without any additional context or response from the administration. In response to the criticism, Rouhani called on opponents to assist the government’s efforts. “This is not a time for gathering followers. This is not a time for political war,” the president said.

Some media outlets, and especially the state broadcaster IRIB, have also piled blame on ordinary Iranians for not following official instructions on social distancing. However, in this respect Iranians do not appear to have been any more remiss than the citizens of other countries. The government has thus far resisted the calls to impose a total lockdown. Some authorities have argued that lockdowns inflict too much damage on the economy and represent a luxury the country cannot afford. They say that punitive US sanctions have ravaged the economy, which has nothing in reserve.

Deflecting attention

The Iranian media have for decades now resorted to highlighting the “failings of the West” as a way of deflecting attention away from serious domestic problems. The news agencies Fars, Tasnim and Mehr as well as the broadcaster IRIB have devoted considerable space to the struggles of the US and UK governments in getting to grips with the pandemic.

The Iranian media have focused on four main themes in connection with the outbreak. The first of these is the notion that the threat of a pandemic was played up by enemies of the Islamic Republic in order to depress the turnout for Iran’s parliamentary elections held on 21 February. The second is the conspiracy theory that the coronavirus began life as a bioweapon. The remaining themes are the role of the armed forces in combating the outbreak and calls for sanctions against Iran to be lifted. These themes all have a similar aim: to bring the Iranian people back into line by stirring up nationalism and anti-western sentiments.

Western “plot” against elections

Parliamentary elections went ahead as planned on 21 February, despite the fact that opposition groups and foreign-based Persian-language news outlets had been warning for weeks beforehand that the coronavirus had already reached Iran. The first deaths attributed to Covid-19 were officially confirmed on 19 February.

According to the official tally, the turnout for the election was 42% — the lowest recorded since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. State officials immediately blamed this on enemies of the Islamic Republic, who they said had exaggerated the threat represented by the virus to deter people from turning out to vote.

Two days later, in comments published on his official website, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei dismissed reports of a coronavirus pandemic as “western propaganda”, saying that “[it] began a couple of months ago and grew larger ahead of the election” — clearly implying that the timing was deliberate.

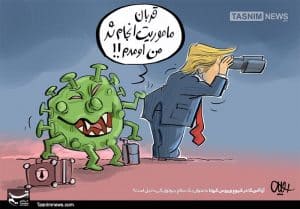

Source: Tasnim News Agency

These arguments were echoed by the media.

Tasnim published a cartoon on 21 February 2020 suggesting that the “rumours” put about by the western media had failed to deter the Iranian people from voting — to Washington’s dismay. Another cartoon aired by the state broadcaster implied that foreign-based Persian-language news outlets had been spreading a virus more infectious than coronavirus: fear.

At this time, IRIB was still insisting that the danger represented by coronavirus had been exaggerated. TV anchors and talk show hosts regularly sought to reassure the public that Covid-19 was no worse than ordinary flu. During a live show on 22 February, one IRIB presenter, Atefeh Mirseyedi — who was introduced as a physician — said that she had contracted the virus and had recovered from it. Within a few weeks, the official narrative had changed and the same presenter had a change of heart. On 23 March Mirseyedi again said that she had developed Covid-19, but on this occasion she warned the public that it was an extremely dangerous disease.

Bioweapon conspiracy theory

The Iranian authorities have been receptive to a conspiracy theory that surfaced early on in connection with the coronavirus, to the effect that it began life as a US-produced bioweapon. These allegations were widely reported by Iranian media, especially those with ties to the IRGC or the Supreme Leader’s office.

For example, between 1 February and 28 March 2020 Tasnim published several articles devoted to the bioweapon theory. It also published an article “detailing” the alleged history of the United States’ use of biological warfare.

And on 22 March, the Supreme Leader made a televised address to the nation in which he said that Iran would not accept any assistance from the US, citing this conspiracy theory. “I do not know how real this accusation is but when it exists, who in their right mind would trust you to bring them medication?” Ayatollah Khamenei said. “It may be that your medicine is a way to spread the virus more.” He also alleged that the virus was “specifically built for Iran using the genetic data of Iranians which they have obtained through different means.”

Source: Tasnim News Agency

Similar allegations had already been made by IRGC chief Hossein Salami, who suggested on 5 March that the coronavirus could be a US-produced bioweapon. During a speech delivered in the city of Kerman, he said: “We will prevail in the fight against this virus, which might be the product of an American biological [attack], which first spread in China and then to the rest of the world.” Salami added that “America should know that if it has done so, it will return to itself.”

On 2 March, Tasnim published a cartoon depicting the coronavirus telling US President Donald Trump: “Mission accomplished sir, I’m back.” The caption reads: “Does the United States have a hand in spreading coronavirus as a bioweapon?”

Role of the armed forces

On 12 March, the Supreme Leader issued an edict — published on his official website — instructing the armed forces to lead the battle against the novel coronavirus. Since then, the Iranian media have repeatedly highlighted the role of the IRGC in the fight against the virus.

The Revolutionary Guard Corps conducted a nationwide biological defence drill in late March, which received extensive media coverage. IRIB devoted considerable airtime to the drill, while news agencies published numerous articles and photo reports on it. IRGC’s emblem and pictures of slain IRGC Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani – who was assassinated in a targeted US drone strike on 3 January – were dominant images in the coverage. The regular Iranian Army received considerably less coverage, despite the fact that it has set up field hospitals across the country.

Both Iranian officials and the media use the language of war in describing efforts to halt the spread of the coronavirus.

Both Iranian officials and the media use the language of war in describing efforts to halt the spread of the coronavirus. Terms frequently used include “forefront”, “battle against corona” and “anti-corona maneuvre”. Given that the armed forces have been leading the fight against the virus in Iran, it is perhaps not so surprising that the military leadership uses battle analogies to describe their role.

Iran is not alone in this respect: a tendency for leaders to use military terminology to describe the fight against the coronavirus has also been observed in other countries. However, elsewhere the use of such terminology has not gone unchallenged. For example, in an article for the Atlantic published on 31 March, Yasmeen Serhan explained why invoking wartime imagery in connection with the coronavirus pandemic was an “imperfect parallel” that could have unintended consequences. While some Iranian social media users have also questioned the wisdom of using such imagery, the regular Iranian media have failed to challenge the practice. This is yet another example of the Iranian media’s reluctance to subject official policies to critical scrutiny.

Sanctions

Iranian authorities and news outlets regularly claim that US sanctions against the country have undermined its efforts to curb the outbreak. They say that the sanctions should be lifted on humanitarian grounds.

Some Iranian media outlets printed translations of editorials in the Washington Post and New York Times calling for the easing of sanctions. The Persian translations appeared on 26 March, only a day after the editorials were published. Iranian media also reported on 27 March that the sanctions issue had been raised by prominent American politicians such as former Vice President Joe Biden, Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, and Democratic members of the House of Representatives Ilhan Omar and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

While US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo hinted on 31 March that Washington could rethink the sanctions against Iran in the light of the coronavirus pandemic, the US administration has not yet come up with any concrete proposals for this. In response to Pompeo’s comments, President Rouhani said in a televised cabinet meeting on 1 April 2020 that “The United States lost the best opportunity to lift sanctions […] This could have been a great opportunity for Americans to apologise […] and to lift the unjust and unfair sanctions on Iran.” However, Rouhani insisted that “The sanctions have failed to hamper our efforts to fight against the coronavirus outbreak […] We are almost self-sufficient in producing all the necessary equipment to fight the coronavirus. We have been much more successful than many other countries in the fight against this disease.” According to some observers, the president’s comments were specifically tailored for the domestic audience and were intended to reassure Iranians that the situation is under control.

Reliance on social media

As a result of the decades-long one-sided news coverage of mainstream Iranian media, there is a very low level of trust in these media. Millions of Iranians turn instead to social media as their favoured news source. The past weeks have seen a lively debate on Iranian social media over the authorities’ handling of the crisis. Many Iranians have little faith in the authorities’ competence and believe that the state is covering up the extent of the outbreak.

Iranians have taken to social media to share information on social distancing and good personal hygiene practices while at the same time criticising the state-run media for failing to adequately educate the public on the risks of the pandemic.

However, the lack of impartial and credible sources means that misinformation is rife. Some Iranians have given credence to online misinformation telling them that drinking industrial-strength alcohol offers protection against infection – with predictably tragic results. Recourse to such “remedies” has resulted in hundreds of deaths and numerous emergency hospital admissions, placing further strains on an already overstretched health service.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO.

See “How media worldwide are covering the coronavirus crisis” for a complete list of EJO articles in English devoted to this topic.

Tasnim News Agency cartoons: Creative Commons / Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Tags: coronavirus, Covid-19, dis/misinformation, Media Freedom, Social media, Trust in the media