Reporting project “Fistula, A Life In Shame” by EJC grantees Andrea Jeska and Fabian Weiss.

If you are reporting about a sensitive or even stigmatised topic, it is crucial to remember that your sources are taking physical and psychological risks just by talking to you.

Jill Filipovic has won awards for her global health reporting and political commentary and has extensive first-hand experience on reporting on sensitive stories. That’s why during our training days for our EJC grantees, we invited her to give advice and notes of caution before her fellow colleagues began their field reporting.

Now, we got to sit down with her again so she could share her tangible tips and experiences with you.

When you are covering a sensitive story in a foreign country — what are the main safety measures to start with?

Be conscious when hiring your fixer. Have they already worked on similar stories in the past? What are their feelings about your topic?

If, for example, your story includes abortion as an element and they express strong opposition to abortion rights, they might not be the right person to work with. It might be worthwhile to ask other journalists about their experiences here.

If your story tackles sexual violence, you might consider hiring a female fixer, or — as there aren’t many — at least a female translator so that your sources feel safer.

Reporting project “In The Wake Of Violence” by EJC grantee Hanno Charisius.

In your first meeting, you need to clearly lay out that any conversation they facilitate is private and confidential, and not to be discussed with anyone. Tell them that if this confidentiality is broken, it’s professional malpractice and means they may not be hired again. Be very clear here — this is crucial to protect your sources.

But the homework does not end here.

What else should be researched ahead of contacting your source?

If you’re reporting in a community that you are not a member of, or don’t know much about, seek out experts before you go. Ask them how the sensitive topic is perceived in the community. What are the taboos around it, how is the public discourse shaped? This is important information to protect your source.

Try to bring in well-meaning experts where possible. Look up if there are reliable community organisations or NGOs working in the area. These are great groups to reach out to, as they often have folks on staff who have existing relationships with survivors and can help facilitate a conversation.

They also tend to be more interested in the well-being of the people they work with than in a journalist getting a story. That can be frustrating for the journalist at the moment but is ultimately a good thing for the source to have a trusted advocate in the room with them.

And what do we need to keep in mind when we are in contact with our source?

The golden rule: no surprises. When talking to your source, the most important aspect of all is transparency. You need to get their informed consent before the interview.

This includes explaining aspects that might not be as clear for them as they are for you. For example, that an online publication in a different country can be read by anyone anywhere in the world and is searchable.

Remember also to explain journalistic norms like “off the record” vs “on the record” as they may be understood by the powerful and educated, but aren’t common knowledge for a lot of average people around the world.

Clear expectations up front go a long way and make sure everyone feels like the process was fair. Apart from these measures you should put into place, it’s also important to remember what your source has gone through. This might affect them in the way they tell their story.

Can you expand on that?

This touches on a whole other important aspect of dealing with sources telling sensitive stories. Aside from protecting their identity, you’ll need to make sure not to threaten your source’s mental health by trying to push them towards a “clear” narrative.

This means: If your source has had a traumatic experience, it might change how they act, make them even seem robotic, cold, or “not how a victim should act.”

Their discourse might not seem to be coherent, or important details might be missing. Remember to provide support, empathy, and time. You have to corroborate what they tell you, so don’t let crucial details go out of misplaced empathy.

But do have patience, and don’t write off a source’s story just because they tell it differently from what you expected.

Also remember: It’s fully within the ethics of our profession to help a source connect with psychological and social services if they need them. While you cannot give them money or pay for their therapy, if you know of an organisation helping victims in their area, pass the information on.

How can you protect your source in the publishing process?

This is of crucial importance. Discuss with them how they want to be identified. Keep in mind that just giving someone a pseudonym is not the same as protecting their identity.

If there is a photo element to the story, also take care that they are not identifiable. Understand that, as an outsider, you might miss details that could identify your source. That’s why, if possible, let them see how they are being shot so they can flag any of those issues on the spot.

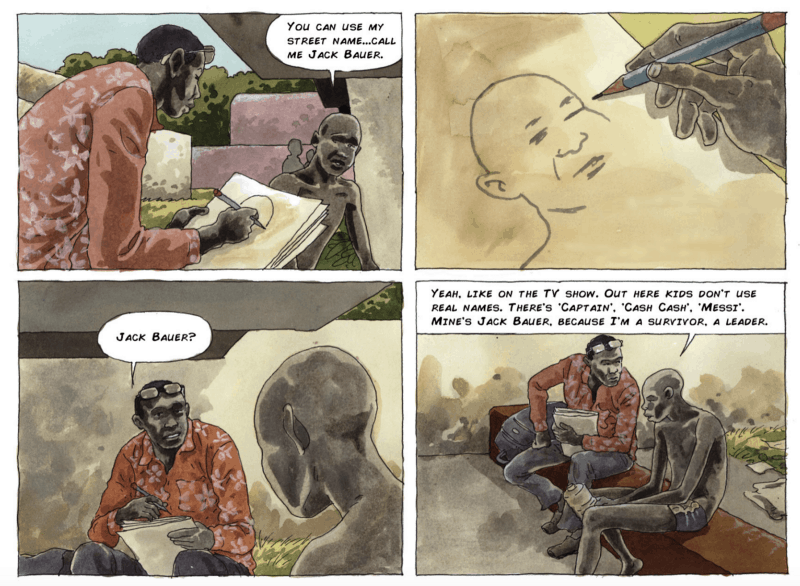

Didier Kassai’s & Marc Ellison’s House Without Windows, graphic novels can be used as a creative way to protect sources’ identities.

Make sure that in any media appearances or public discussions, the level of confidentiality you promised your source is maintained. Stick to the pseudonym you gave them, and don’t offer details that weren’t in the story if you aren’t totally sure they won’t identify them.

What last advice would you give to journalists?

Remember that being compassionate towards your source doesn’t mean compromising your ethics or dropping your professional obligations. It’s still crucial to corroborate essential claims your source is making.

Explaining your source why you need corroboration always helps. Make it clear that it has nothing to do with whether or not you believe their story. Clarify that the additional evidence will make their case stronger and make them better situated.

Sometimes sources may come back and ask for their stories to be changed or retracted altogether. In these cases, it’s crucial that you are transparent from the start and have your conversation on the record.

A thorough conversation can often help to smooth out these wrinkles. It can also be helpful to speak with the intermediary who connected you with the source to get a deeper understanding of their situation.

You might also be interested in Working With Whistleblowers In The Digital Age: New Guidelines.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO.

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Tags: anonymity, Governmental Surveillance, Insights, Internet Surveillance, Investigative Journalism, Journalism, News, privacy, protection, reporting, Safety, Security, sources, state surveillance, Whistleblowers, Whistleblowing, witness