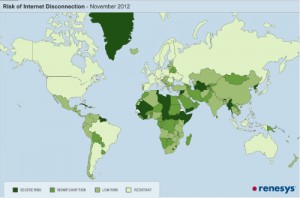

Syrian officials recently shut down Internet access throughout the country for several days, a common tactic for nations attempting to inhibit internal and external communication. According to new research, sixty-one additional countries are at severe risk of Internet disconnection. The Internet is the final battleground for freedom of speech in countries where media and information is under government control and censorship filters communication. Egypt and Syria are the latest examples of nations where Internet access has been blocked in order to stop outgoing and internal communication. During the Arab Spring, in February 2011, then President Hosni Mubarak’s regime succeeded in disconnecting all of the country’s Internet providers and earlier this month Bashar Al-Assad’s government was able to take Syria offline, blocking digital communication during one of the most critical moments in the country’s ongoing civil war. Seventy-seven Syrian networks were shut down and 92 percent of the Syrian Internet was disconnected, Wired US reports. According to Renesys, an American company specializing in network monitoring, all of Syria’s eighty-eight IP address blocks were unreachable, “effectively removing the country from the Internet.” How is it possible to completely block the World Wide Web? And where could it happen again?

A new reportjust released by Renesys provides some frightening statistics about how easy it is to completely disconnect the Internet in at least sixty-one countries, including Greenland, Yemen, Ethiopia, Tunisia, and Algeria, among others. According to Renesys the reason is simple: “In some countries, international access to data and telecommunications services is heavily regulated. There may be only one or two companies that hold official licenses to carry voice and Internet traffic to and from the outside world, and they are required by law to mediate access for everyone else.” In these cases it is extremely easy for the government to issue an order to take down the Web. Without even making a phone call to Internet providers, remote censors can cut power to central facilities and literally unplug Internet access. Due to the ease of removal, decentralization has become a key defense for those nations attempting to protect their access.

Countries that have the ability to inhibit Internet access are those where “the number of providers that get to exchange traffic with their foreign counterparts is very low” says James Cowie, Renesys’s chief technology officer. The more external providers a country relies on, the more difficult it will be to disconnect Internet. According to Renesys, “without some strong legal prodding and guidance from the telecoms regulator, significant diversification in smaller markets with a strong incumbent can take a long, long time.” Countries with only one or two companies “at the international frontier” are the sixty-one nations who are at severe risk of disconnection. Nations with fewer than ten providers are exposed to sensible risks; those with more than ten but less than forty internationally-connected providers are at a low risk because a complete blackout would take days to initiate and will require a great deal of maintenance. Only countries with more than forty providers are “extremely resistant to Internet disconnection,” including the United States, Netherlands, Canada, and thirty-two other nations.

In other countries the situation varies. For example Afghanistan’s situation is unique as its national Internet is well connected with its neighbor states. This is a product of regional fragmentation, with the Afghan Internet being constructed from terrestrial service outlets originating in the countries of Uzbekistan, Iran, and Pakistan. As a result, it would be very difficult for the government in Kabul to turn off the Internet, but with sixty-one other nations vulnerable to disconnection – which will be the next Syria?

Tags: Arab Spring, Bashar Al-Assad, Egypt, Hosni Mubarak, Internet Censorship, Internet Freedom, Internet Surveillance, Renesys, Syria, Wired