Every photographer has his or her own perspective on the necessity of publishing difficult or abrasive images.

Every photographer has his or her own perspective on the necessity of publishing difficult or abrasive images.

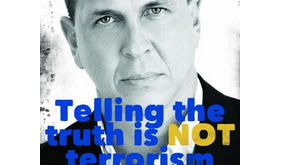

“It’s my job,” is not a common refrain among photographers. More often the job itself is accompanied by a strong sense of human solidarity, which apparently finds conflict with the obligation to tell a story through images. It goes without saying that situations arise in which journalists can find themselves having to choose between the importance of reporting and helping those in need. What happens in those moments may alter livesindefinitely. Alessio Romenzi, a photojournalist based in some of the world’s hotter spots, provides us with a bit of insight on the subject from the Middle East.

Q: Alessio, what motivated you to take up this profession?

What a heavy question. I am not a veteran – in Libya I had my first experience with war photography and I’ve been working as a photojournalist for little over a year. Not to mention that I am not very good with words, either written or spoken. Before answering the question let me clarify a few things: It is not by chance that I work only with images, I did this by specializing in sports events in the beginning, horse shows in particular. In 2008 I attended a Master’s course in photojournalism at the ISFCI in Rome and this opened my eyes to new possibilities with my photography. I was able to recall what my eyes saw using a new, different language, in a dangerous context, often with very little available time. I could allow people to see the rhythm and energy that shaped each day, and those which continue to shape my professional and personal life in territories where it is only fair to show the world what we see. The Middle East has been a true testing ground for me, so dense with contrast and stimulation that it taught me more than any school could have. I can say that this is the place where my job really began, and maybe it is only at these latitudes that you ask yourself whether it is essential to show your photographs without mediation. Add to this that lately, with regard to North Africa, a new relationship has developed between war reporters and humanitarian workers, with these two operations growing closer to some extent, creating new responsibilities and skills for both.

Q: Have you ever found yourself having to choose between reporting and helping someone?

Yes, and I have no doubts. First and foremost I am a human being, and so when my help was really needed I shifted the camera to the side and used my hands to do what was necessary, perhaps missing a fine photograph or two, but something I certainly do not regret.

Q: Some not only photograph and recount the war, but mediate between the two parties in conflict.

In Jerusalem the Search for Common Ground, an American Non-Governmental Organization, created an information channel on the Web, the Common Ground News Service, used to monitor Arab and Israeli news reports and find those that propose non-violent solutions or pacifist initiatives which they then distribute to people. But are these organizations really useful, and don’t we risk contamination among professions?

I know the kind of figure you are talking about, and I know the channel you mention. Search for Common Ground might even work, because everything helps people form an opinion, but as always, in the chaos and surplus of news provided by the media, it is useful for the end user to implement his knowledge with balanced news. In the end it is the user who determines the usefulness of the news. As far as contamination is concerned, my ideas are clear. I, too, divide my time between the AFP, as a stringer, and non-governmental or UN organizations who work in the Israeli-Palestinian territory. I work both in Israel and in the West Bank and Gaza.

Q: And you have also been to Egypt and Libya?

Yes, and there I measured myself for the first time against events that will end up in the history books. To say that it was interesting to witness these momentous events, to live through those moments and breathe that dust, is to say little. I found myself immersed in a sea of emotions I could not have imagined before, and it was almost too easy to take pictures. To those who ask me what could possibly be attractive about being crushed in the crowd at Tahrir square, or what it feels like to be on the ground threatened by the Libyan leader’s bombs, I reply that those are the most genuine human situations I have experienced. These events are created by men who I consider “naked” because their intentions were so clear. In their eyes, and at times in their recklessness, they only had one purpose, a desire for freedom. I am talking about men willing to risk their lives to get what they wanted, capable even of setting themselves on fire in front of a camera lens.

Q: Would those people have done the same thing if they didn’t have the international cameras on them?

In Libya we saw men applying their poor skills as warriors and strategists to the battle effort, and for good images all you needed to do was be at their sides. I’m not only speaking about the times they were waiting and organizing because the war, or however you in the West want to call it, must be documented fully – you had to be there when things were happening as well, when there were attacks. At that point the photo, the witnessing is automatic, almost like a live recording that captures all the noise. The facades fall away and in your lens you find clean and honest people, who show themselves, whether they want to or not, in their animal state. The crude, painful images, the ones that make you squint or turn away, are part of the story you are telling, and therefore must be shown. Perhaps they are repugnant, but war is crude, cynical, a bitch, and if anyone, even among journalists, still doesn’t understand that, it’s time they face the facts. I’m not only speaking about the images from the front, but also those from behind the front lines – the people who, even though they are not directly involved, suffer the consequences of the conflict. There are the children who will pay for these terrible experiences in the years to come. There is hunger, cold, sweltering heat, poverty, because this job doesn’t only consist of bombs and mutilated people – and the people who work in humanitarian organizations alongside the reporters know this well. At times the most difficult images to take are exactly those.

Alessio Romenzi, a freelance photographer in the Middle East, is represented by the CORBIS photo agency.

Translated by Ann Wise

Tags: Alessio Romenzi, Common Ground News Service, Conflict Photography, CORBIS, ISFCI, Non-Governmental Organization, North Africa, Photojournalism, Search for Common Ground, War Reporting