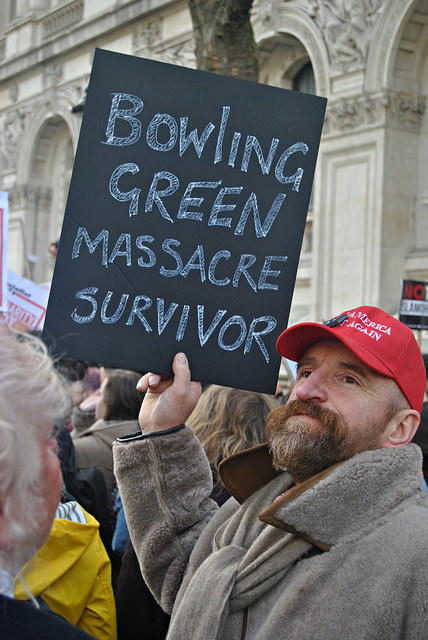

Alternative facts: The so-called ‘Bowling Green massacre’, described by Kellyanne Conway to justify Donald Trump’s immigration order, never happened.

Shortly after Kellyanne Conway defended White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer’s false statement about attendance at Trump’s inauguration as “alternative facts”, the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism asked a seemingly simple question: how should journalists cover powerful people who lie?

The starting premise, as outlined by authors Alan Rusbridger, Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, and Heidi Skjeseth, was that “the world is not black and white, neatly divided between truth and untruth, but there are such things as lies, intentionally false statements.”

“To find truth and report it, and to keep the public informed about public affairs, journalists need to be able to deal with this, especially when powerful people lie in blatant and self-interested ways.“

Rusbridger, Kleis Nielsen and Skjeseth created an open Google Document and invited people from all over the world to share their thoughts and suggestions on how journalists should cover powerful people who lie.

Over two weeks from January 26 to February 9, more than a hundred people contributed ideas. The document was shared widely on social media and covered by news organisations in many countries. The number of responses saw the paper grow to more than 50 pages.

The full document is available here.

Contributors came from many different backgrounds (journalists, concerned citizens, academics) and countries (ranging from stable democracies to autocratic states with everything in between). “Not everyone agrees on how journalists should cover powerful people who lie. The responses are not representative, they are not exhaustive, and they will not “solve” the problem—but they are interesting and worth sharing,” the authors wrote.

Below are the most important areas of agreement (the do’s and don’ts that most contributors agree on) as well as the most important area of disagreement—whether journalists should try to be impartial or whether they should take a stronger stance.

Do’s – what journalists should do

- Call lies lies and falsehoods falsehoods. Not doing so undermines credibility and trustworthiness with the public (even if it may infuriate partisans).

- In turn, cover the partisans who support powerful people who lie. Understand their world view, give voice to their perspective.

- Get outside the bubble, away from official sources and insider group-think.

- Focus on the substance, not the form, so follow the money and cover consequential and binding decisions made, rather than provocations and conspicuous displays of ‘doing something’.

- Collaborate. Follow up on each other’s questions. Share notes on sources’ credibility.

Don’ts – what journalists shouldn’t do

- Don’t lead with the false statement in the headline or the standfirst, and don’t succumb to false equivalence (‘Views on shape of the Earth differ.’)

- Don’t let yourself be distracted by endless tweets and provocative asides—cover the story, not the person. Focusing on every provocation and false statement ends up rewarding the lies with publicity.

- Avoid going live unless absolutely necessary. Consider not broadcasting live press conferences and interviews with sources who are known to be unreliable. Breaking news coverage makes real-time fact-checking hard and publicise the lie.

- Don’t give publicity to unreliable sources. It may produce engaging and provocative content, and in turn bring in an audience and advertising, but long-term, it undermines credibility.

- Treat politicians you like or agree with differently than those you dislike/disagree with. Please don’t be one of those journalists who end up sharing false information on social media about politicians they personally do not support.

This is an abridged version of an original article published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Image: Loco Steve, Flickr CC licence

Tags: Crowd-sourcing, crowdsourcing, fake news, media, Online journalism, Press freedom, Propaganda, Research, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Social media, Twitter