Experimental reporting? The New York Times broke with editorial tradition to call out Donald Trump’s “lies”.

Journalism is entering a period of “experimental editing and experimental reporting”, according to Mark Thompson, chief executive of The New York Times and former director general of the BBC. Typically, journalists and social scientists look to the past to help understand the future, but recent political and social upheavals have meant that models from history may no longer be as useful.

“We are in the middle of a gigantic experiment. When you have massive discontinuities… such as now, it is almost like going back to basics. Listen to what politicians say, observe what they do and report it. Try to understand it, but be pretty cautious now about second-guessing the future with reference to the past, because it may not apply,” Thompson told an audience at the University of Oxford last week.

In his book, Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong With the Language of Politics, published in September this year, Thompson argues that political rhetoric is becoming increasingly simplified, crude, polarised, and based on opinion, rather than fact.

The recent US presidential election, and Brexit in the UK, have only confirmed these views, he said, adding that social media and algorithms, systems by which information is increasingly shared, also favour “the simpler, the brasher, the more popular message”.

By contrast, traditional political reporting appears “tired” and journalists need to find new ways to reach and inspire their audiences with thoughts and ideas.

Journalism must adapt to the changing political environment

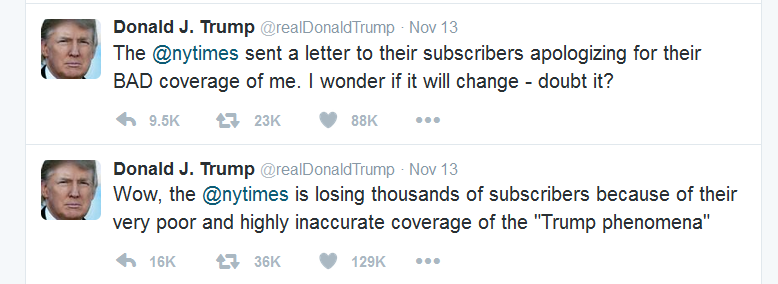

Thompson described how The New York Times introduced a new approach to reporting during the US presidential campaign, when, in a front page news article, one of Donald Trump’s statements was described as a “lie”.

“When The New York Times decides it is necessary to fact check and assert inconsistency and falsehood – [at the same time] as a statement is reported, it changes the landscape,” he explained.

The New York-based national daily newspaper, which has around 1.5m digital subscribers, “strives for impartiality” in its news reporting, although its opinion pages are generally liberal. During the presidential campaign the paper tried to hold both candidates equally to account, although this proved controversial. Some readers complained the newspaper’s negative reporting of Hillary Clinton damaged her chances of winning, even though the paper’s editorial board had endorsed her as its favoured candidate.

“I worry about any journalism that tells people what to think”

Thompson defended the newspaper’s position, arguing it should not be a news reporter’s job to promote one candidate over the other. “I don’t understand what politically motivated journalism or politically-aligned journalism are. For me [reporters should] try to find out what is happening and to be open-minded about everyone … to allow your audience to make up their own minds about what is going on. I worry about any journalism that tells people what to think … to me that is a different activity. I take a very austere view of what impartiality consists of.”

“An impartial news organisation should strive for fairness and objectivity. Impartiality is not a state of grace which any institution achieves and allows it to rest on its laurels. I always like to say I work for institutions that at least try to be impartial.”

He dismissed recent criticism over the way the BBC reported Brexit: “You mean the coverage was distressingly balanced as a result of which there was the ‘wrong result’? I think that gives the game away.”

Users can choose what to consume on the internet, regulation is impractical

Technology companies should not be responsible for moderating, regulating or make editorial decisions about content shared online or via social media platforms. Everything is available on the internet and end users are allowed to choose what they want to consume. “That’s the character of the beast and its not going away,” he said.

Thompson acknowledged the potentially disruptive role of fake news, distributed via social media, but said it was almost impossible to control. “I personally think fake news is clearly undesirable from a civic point of view, but I think it is a small sub-set of our problems. There are sites passing themselves off as news providers with stuff which is not true, but many of these have a satirical quality. How can a machine or a human being tell me what is satire?”

“The people who run Facebook think of themselves as a social platform rather than as a news provider. I am sure they are decent people but understandably they do not want to take responsibility for what actually happens. So, you have a platform that provides news where the news is chosen in a way that none of us understand and in an environment where they are saying we cannot be responsible for the results.”

Education is most effective way to control fake news

The best way to control the spread and impact of fake news is through civic education. “I would never recommend that one of my children, or any young person, should look at [social media platforms] as their sole source of news. You have no idea how the stuff’s been put together. It is being run by people who do not feel responsible for the results.

“I am not saying don’t use your Facebook news feed, I am saying that if that is your sole source of news, you have to think of provenance, accountability, of what you are seeing and what you are not seeing.”

A transparent, accountable line, from reporter to news app

The inability – or failure – of technology companies to guarantee the veracity of news shared via popular platforms could be an opportunity for quality news organisations to gain audience trust, both on the left and the right of politics, according to Thompson.

This is because the news gathering process at most legacy media is transparent: “At The New York Times, Dean Baquet, the editor, chooses what appears in the paper – and if you do not like it, email him. The publisher and the board are there behind him as well. In fact, we can usually draw a straight line from the article appearing on our smartphone app all the way through to a reporter standing on the street with a notebook.

“That is really valuable and it seems to me that rather than thinking we can somehow repackage social media as a phenomenon, in a way that somehow sieves out all the nasty stuff and all the trolling and visciousness, and all of the fake news – which I submit is not going to happen – what we can do is try to prove the case for, and market the hell out of, the idea of proper provenanced, accountable journalism.”

Beyond the ‘Trump Bump’, how to inspire audiences

In recent weeks Donald Trump has personally helped to promote The New York Times, although it is unlikely he intended to. Each of the six or seven times he has tweeted an insult about the newspaper, (describing it as ‘failing’ and ‘dying’), subscription sales experienced an “astonishing surge”, increasing around ten-fold, Thompson said.

This so-called ‘Trump Bump’, has had a positive and unexpected impact on subscriptions for a number of US media outlets. But the challenge will be to keep audiences engaged in the future.

Thompson, who recently spent over an hour with the US president-elect, coming away with the impression that Trump is “ready to start work”, urged journalists to find new ways to reach audiences and to hold the new presidency to account.

“The frustrating thing is that in the world of politics and public policy we have somehow lost our collective taste for thoughtfulness and engagement with ideas.…the media should figure out a model about trying to do politics in an engaging and interesting way, rather than the tired way we do it at the moment.”

pic: NYT screen shot, September 27th

Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong With the Language of Politics

Mark Thompson was speaking at Nuffield College, University of Oxford, Friday 9 December, 2016.

Tags: BBC, BREXIT, Donald Trump, fake news, Hillary Clinton, impartiality, Mark Thompson, New York Times, Social media, university of oxford