The media situation in Yemen can be explained in one word: chaos. In 2011, the Arab Spring began with a mass protest in Sana’a, Yemen’s capital, and quickly spread throughout the region. Faced with an unstable political situation, journalist’s lives are becoming increasingly difficult. Many have to face a situation in which they struggle with governments that do not respect democracy and human rights at the most basic level, such as the citizen’s right to live in safety or have a different opinion.

In a country like Yemen, where fundamental human rights are often violated, journalists and, in particular, war correspondents put their lives constantly at risk. They convey the information from the front lines of the conflict and are always under pressure. Often, they cannot adequately report the truth due to a variety of political actors who try to control their activity. Some media outlets, biased towards one side of the conflict, will furthermore restrict what they can publish.

Many journalists have refused to give up their work, which they perceive as their duty to society, even amidst the growing number of attacks and restrictions against them. Middle East and North African war correspondents who assume this risk, face various obstacles such as pressures and constraints exerted by parties involved in the conflict. These tend to influence and control the work of journalists with varying degrees of sophistication.

Journalists and correspondents have also become the target of attacks from parties involved in the conflict, facing constraints simply for doing their job, such as being banned from accessing different parts of the country. For example, journalists who support revolution and who reject the Houthi rebels’ power are not allowed to be present in territories that are under their control in northern Yemen, while the journalists who are supporting the Houthi rebels are not allowed to report from other zones and cities like Taiz and Aden.

Many journalists also had to leave the country, while others were killed, as happened with Al Masdar correspondent Jamal Al-Sharaabi while he was covering anti-government demonstrations in 2011. Another journalist, Mohammed Al-Absi, was killed because of carrying out an investigation in which he was trying to show the seriousness of corruption in the country; 41 other journalists are currently being held hostage.

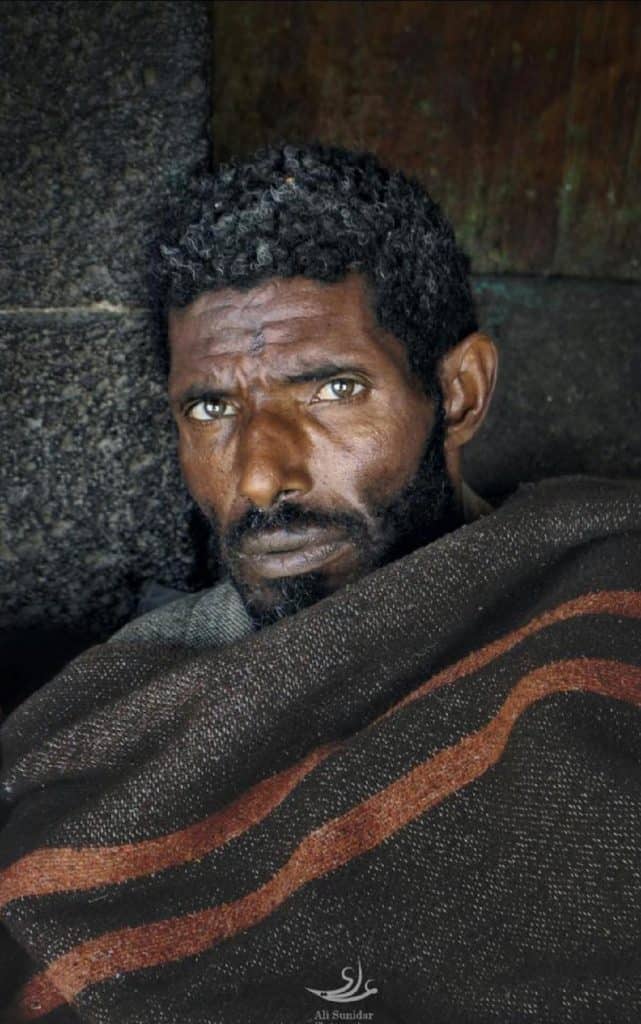

“Scenes of death can not be forgotten, and the effect does not appear immediately, but over years.”

All correspondents I interviewed* have suffered psychological consequences resulting from covering the war in the country. To a lesser scale, they have also experienced physical pressures (death threats) and technical pressures (problems with the real-time transmission of information). As a correspondent with an international media outlet confessed, “certainly death scenes cannot be forgotten, and the effect does not occur immediately, but over years.”

Many correspondents that I interviewed said they depend heavily on official sources, military institutions, representatives of the military authorities, witnesses, media platforms and the Internet. Information obtained off the record also played an important part. Yet, many journalists admitted they have made mistakes in their reporting because of receiving incorrect information from sources.

“Each of the parties involved in a conflict tries to guide the correspondent in her favor… After all, there can be no consensus or agreement on the battlefield because the facts in these conflict zones influence one of the two parties, and the journalist cannot remain indifferent,” one journalist explained the situation. “This does not mean adopting a hostile attitude against one of the parties, but adopting the truth, which in turn is not in favor of any of them.”

A Unhappy Correspondent In Happy Yemen

In ancient times, Yemen was known as “Arabia Felix”, Latin for happy or fortunate. But now it listed as one of the least happy countries in the world, according to the latest UN World Happiness Report. The index is based on aspects such as gross domestic product per capita, asocial assistance, life expectancy, corruption level, and social freedom.

Yemen’s unhappiness is explained by the country’s critical socio-political situation. Yemen is one of the world’s poorest countries. Numerous wars and conflicts have taken place in recent years. And the country is in the middle of a series of conflicts that threaten its stability: the war with Al-Houthi insurgents since 2004, the separatist movement in the south, the existence of Al-Qaeda members in some cities in the country, the changes imposed by the 2011 revolution, military operations launched on a large scale by Saudi Arabia and its allies, and, more recently, terrorist attacks in various parts of the country committed by some cells which are loyal to the ISIS group.

,,I was kidnapped, and kidnapping reflects the journalist’s value”

All journalists I talked to mentioned that they face physical risks (attacks targets, gun nets, ambushes, missiles, trap cars and kidnappings), general risks such as the lack of bulletproof vests, lack of personal security, the payment of money in exchange for personal security, and attachment to the army.

What they experience can be drastic: “I was kidnapped,” explained one correspondent, “and kidnapping reflects the journalist’s worth and the fact that some parties involved in conflict do not like his existence, so they try to stop his voice or instill fear to stop him. Therefore, there is always a conflict between a powerful entity, either a militant group or the armed parties, and a journalist.”

“Because of the feeling of patriotism, many correspondents are subjective or practice self-censorship”

Some of my interviewees have testified that, because of the military authority controlling the territory they were reporting from, their coverage is affected. A correspondent for a local outlet says, “I faced a lot of pressure from the Houthi rebels, I was arrested, and I have a ban on being in a territory which is under their control. In regard to the other parties, I have not faced any pressure, perhaps because I support them.”

Correspondent protection on the front lines is not guaranteed. A former correspondent, retired in the meantime, said: “There is no protection, no guarantee, but an attempt of a calculated adventure, that is, obtaining the greatest guarantees, but the danger waits at every step. ”

In The Theaters Of War, Ethical Rules Do Not Exist

Different parties involved in the conflict in Yemen are constantly trying to influence the correspondents in order to relate in their favor. The geopolitical situation in which a journalist is located can have a major influence on the risks he or she (has to) take(s) to report.

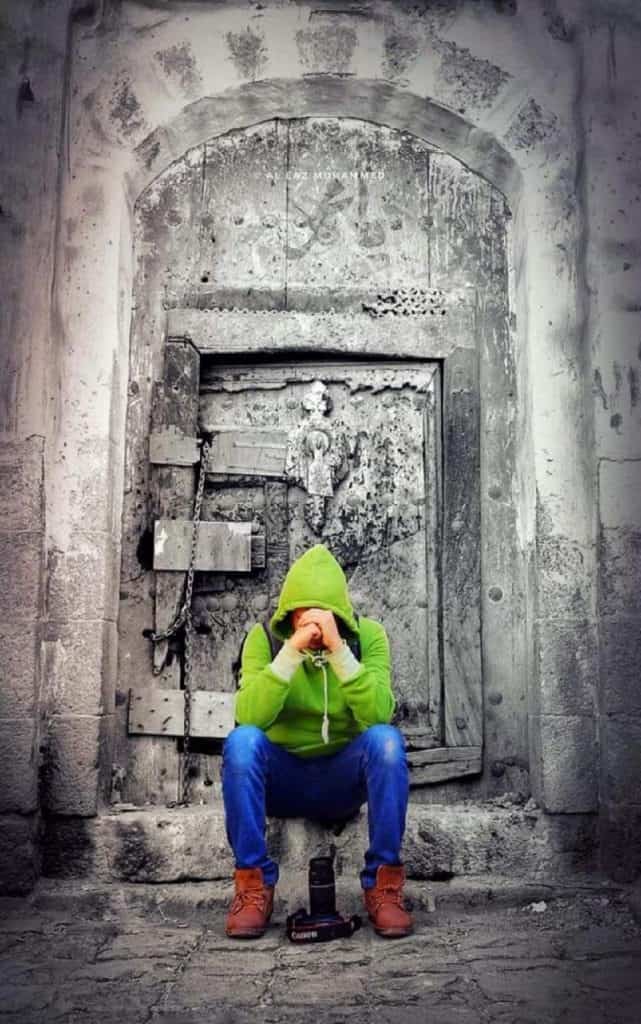

Psychological consequences spurred by being on the front lines of the war may remain long-term or even for life. At the same time, patriotic feelings may mean that correspondents abandon their subjectivity or practice self-censorship.

“It’s very hard to stay neutral. Sometimes I couldn’t help myself and cried because I was psychologically affected, and it was very difficult to talk about neutrality in cases in which we reported on people’s suffering,” said on international correspondent. “The correspondent does not have the ability to convey the vision of both sides and risks to become partisan because of the places in which he is in.”

Being a correspondent in a conflict zone is full of limitations and pressures. Their interest in a creative job, the thrilling life, the risks to find the truth and gaining professional prestige are just a few of the things that motivate them to continue their work. Yet, being a war correspondent is full of risks and the possibility that the journalist loses his life is always existent. That’s why a war correspondent must be mentally prepared for any possibility, because in the theaters of war, no ethical or human rules are taken into account, even for neutral people such as journalists.

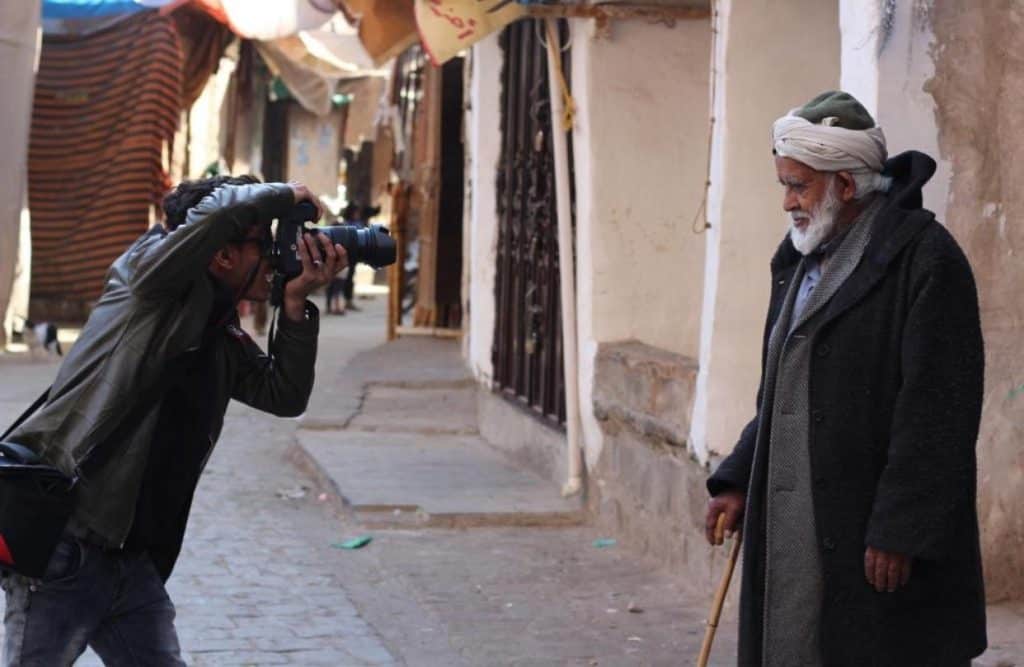

Photo credits: Ali Alsonidar and Mohammed Al-Eez.

You may also be interested in “Neutrality Is Impossible Here”: Reporting Ukraine’s War.

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Twitter.

Tags: conflict, Conflict Reporting, Freedom of the Press, Journalism, Press freedom, reporting, war, war correspondent, Yemen