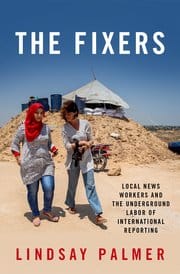

Fixers operate at the point of contact between the local and global. (Image: Pixabay / Public domain)

When Barack Obama, the first black president of the United States, visited Kenya in 2015, it was a major news story across the world. But while reporters from major international news outlets took all the credit for covering the event, hundreds of Kenyan journalists were performing a vital role in the background, acting as guides and translators for their foreign colleagues and generally easing their path. However, for the most part these key journalistic collaborators, with their essential local knowledge, remain firmly in the shadows; their faces are never seen on television and their contribution is rarely acknowledged in public. In her book The Fixers. Local News Workers and the Underground Labor of International Reporting (Oxford University Press, 2019), American media scholar Lindsay Palmer looks at the role of fixers and the conditions in which they work.

Fixers are local media workers who are hired by journalists as translators and guides and can provide various other kinds of assistance. Unlike stringers, who are occasionally mentioned by name, sometimes co-author or co-produce pieces of journalism, and are sometimes contracted to work for media companies, fixers play a role in setting up a piece of journalism, but are not involved in the writing or production process. They occupy one of the lowest ranks in the hierarchy of international news and the part they play has until now been neglected by journalism research, says Palmer. Her book focuses on how fixers themselves – who, despite regional differences, have similar experiences the world over – see their role. Palmer’s study is based on interviews with 75 fixers from 39 countries and draws on concepts from postcolonial theory, global media ethics and critical global studies.

Fixers are local media workers who are hired by journalists as translators and guides and can provide various other kinds of assistance. Unlike stringers, who are occasionally mentioned by name, sometimes co-author or co-produce pieces of journalism, and are sometimes contracted to work for media companies, fixers play a role in setting up a piece of journalism, but are not involved in the writing or production process. They occupy one of the lowest ranks in the hierarchy of international news and the part they play has until now been neglected by journalism research, says Palmer. Her book focuses on how fixers themselves – who, despite regional differences, have similar experiences the world over – see their role. Palmer’s study is based on interviews with 75 fixers from 39 countries and draws on concepts from postcolonial theory, global media ethics and critical global studies.

The book concentrates on the fixers’ own production narratives: their working conditions, how they perceive their role and what this tells us about the organisation of the international news industry and the interdependence of the local and the global. The structure of the book follows the pattern of fixers’ work: it begins with a discussion of how this work is defined, tackles fixers’ different roles and tasks and ends by establishing at what point in the news production cycle is the work of fixers done – namely with the editing and publishing of pieces of journalism.

Based on the interviewees’ responses, Palmer highlights the five main tasks and roles of fixers and devotes a chapter to each of these:

- Conceptualizing the Story

- Navigating the Logistics

- Networking with Sources

- Interpreting Unfamiliar Languages

- Safeguarding the Journalist

Palmer makes a point of flagging up the potential for conflict in each role. According to the fixers, tensions arise, for example, when a journalist turns up with a preconceived story idea and insists on clinging to stereotypical ideas; when a journalist behaves inappropriately when dealing with sources; or when a correspondent refuses to heed the fixer’s advice and so risks exposing them both to danger. The latter behaviour is all the more reprehensible as the fixer, unlike the correspondent, often does not have the option of just getting away and so continues to be at risk afterwards.

Power structures and ambiguities

Palmer often emphasises the power structures within which fixers and correspondents or other journalists operate. Often – if not always – fixers work in post-colonial contexts, and geopolitical or market power structures reflected in the organisation of the international media have an impact on the relationship between reporters and fixers. This means that it is often the interests of the reporters or the major media companies that determine the selection of topics and the framing of a story. At the same time, however, their local expertise gives fixers an authority that makes them indispensable for news production and gives them a certain influence. They can perform an invaluable function in making a journalist aware of under-reported aspects of a topic. On the other hand, they can also themselves be influenced by the mainstream perception of a story, which can lead them to oversimplify the presentation of it instead of shining a light on aspects that tend to be neglected by the international media.

On the evidence of the interviews, fixers appear to perceive their role as predominantly performative, in that they act as go-betweens functioning at the intersection between cultures, languages and local conditions. They work at the point of contact between the local and the global and in the field of tension between understanding and misunderstanding, connecting and separating. This means that they contribute to the production of culture and the way in which culture is shaped by the media (as set out by cultural theorist Stuart Hall in his writings on mediatisation). Palmer also references historical perspectives on the roles of translators and people who occupy the borders between cultures that were shaped in colonial times.

Global versus local

The confrontation and cooperation of a global media group with the realities of the local has great potential for productivity, says Palmer. On the other hand, racial or ethnic discrimination and a tendency to undervalue the contribution of fixers can have a seriously detrimental effect not only on the relationship between journalists and fixers, but also on media content. Here Palmer follows critical global studies, which instead of simply describing the status quo take a more activist approach and highlight inequalities and injustices that need to be addressed. She contrasts the capitalist system of media companies with the creative potential inherent in cultural differences.

It is not only in the Global South that reporters rely on fixers. The system is also in use in Europe and the United States, and correspondents occasionally resort to using fixers even when covering domestic news stories. Yet the relationship between journalist and fixer is often seen as a binary juxtaposition of the global and the local – an assumption that Palmer challenges. She repeatedly points out that the understanding of the local fixer on the one hand and the global media company on the other hand hardly begins to describe the complexity of the relationship, as fixers do not always operate only at the local level, but often have international experience themselves, while correspondents also have perceptions based on their own local experience, which they bring to the collaborative project. The global and the local come together and influence each other.

Who ‘owns’ the story?

Since a fixer, unlike a stringer, does not write or produce, this prompts the question: Where does the “news fixing” end? At what point does the fixer relinquish responsibility and hand over the story in which he or she has invested so much planning, work and expertise to someone else (the journalist)? According to Palmer, some fixers actively seek to “delete” themselves from a story after researching it, cutting all ties between their person and the journalistic product. Who “owns” the story? Some fixers say that they consider their role to be over once they are paid, that they don’t see themselves as journalists, or even that they are relieved to have less responsibility for the product than the person who writes it. Others, on the other hand, emphasised how much it meant to them to be involved in the construction of the story and for their contribution to be appreciated. How clearly are these roles defined beforehand? Another controversial point is the fact that fixers are rarely given bylines. Some are not bothered by this and in some cases even feel that their anonymity and the fact that they carry a lower burden of responsibility helps to ensure their safety, especially in areas where there are restrictions on press freedom. For others, however, it means that they are rendered invisible, making it difficult for them to build a professional portfolio and denying them any ownership of the story.

The economic aspect of news fixing has the potential to generate tensions, too. While some fixers say that they earn more than other local journalists who do not undertake this kind of work, others report problems due to the difference in financial systems between their own country and the ones where the media companies who use their services are based. Problems can also arise as a result of journalists’ lack of understanding of the fixers’ financial situation or an unrealistic idea of costs combined with a lack of communication.

Lindsay Palmer’s comprehensive study offers an important insight into an area of international journalism that rarely receives much attention and sees it from the perspective of a group that is as marginalised as it is significant. She gives the topic a solid interdisciplinary theoretical framework that combines concepts derived from journalism and media studies with a framing and calls for action taken from cultural studies, especially postcolonial theory and critical global studies. Palmer very persuasively highlights the ambiguities, grey areas and tensions that characterise the subject of news fixing, especially in the sphere of intercultural cooperation, and shows which questions and possibilities for practical action arise from this topic. The emphasis of the book is on listening: to the stories and experiences of fixers from different parts of the world, as reflected in their own words in numerous quotations.

This review first appeared in German on EJO’s German-language site.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO.

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in “Research: The Role of the Fixer in Foreign News“.

Sign up for the EJO’s regular monthly newsletter or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Tags: critical global studies, intercultural cooperation postcolonial theory, mediatisation, news fixing