Photo: Marco Verch/ Lizenz: CC-BY 2.0

By Johanna Mack, Sara Namusoga-Kale, Merle van Berkum, Enoch Sithole, & Susanne Fengler

Climate change: Deserted land in journalism education

Even though climate change has emerged as the key global challenge, and climate coverage is at the top of the media’s agenda in many countries, it is not a consistent part of journalism education across continents yet.

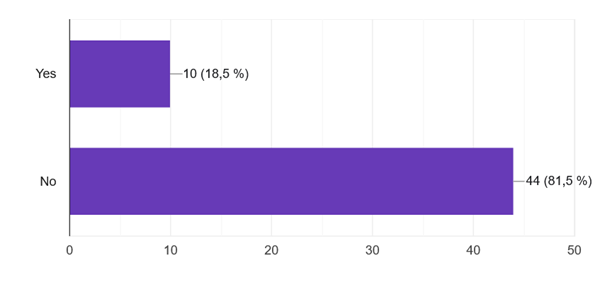

In our most recent exploratory study, jointly conducted by the European Journalism Observatory (EJO) and the African Journalism Educators Network (AJEN), 2/3 of international journalism educators responding said their institutes do not offer courses on how to cover climate change1.

This results in a lack of skills among journalists, which might have an impact on newsrooms, and also affect public debates. Media professionals without substantial training and knowledge might be more vulnerable to strategic communication from the many national and international stakeholders in the field, from industries to NGOs.

Our results are consistent for Europe – where industrial countries are responsible for considerable amounts of emissions, and now also experience climate-change related disasters more frequently – as well as for Africa, where a high share of the world’s population directly affected by climate change lives. In many cases, climate change forces Africans to migrate.

While most journalism educators think that climate change is sufficiently represented in the media of their countries (the European more than the African respondents), survey participants in both continents agreed that it is not yet sufficiently represented in journalism education. In general, only 35% answered that their institution’s curriculum includes coverage of climate change and its consequences in courses or training programmes, while 64% said the curriculum does not include these topics. In Europe and in Africa, the ratio is fairly similar with 64% according to the European and 68% according to the African participants.

Is climate change sufficiently taken into account in journalism training in your country?

If included in the curriculum, climate change reporting appeared more often on the bachelor’s than on the master’s level. In those cases, 60% of occurrences were in mandatory classes and 40% on a voluntary level. Courses which dealt with climate change reporting were sometimes general classes, for example on general broadcasting and reporting. However, the topic also appeared in more specialized courses such as science journalism, development journalism or environmental studies. In some cases, the respondents reported that it was taught by guest lecturers or in specific workshops.

The participants mentioned a variety of reasons why the topic is not yet included. Lack of flexibility in the curriculum, lack of training of teachers and lack of resources were stated as the most prominent reasons. However, also a lack of interest amongst either media or students was mentioned, as well as lack of political freedom; and finally the issue that climate change is only one of several important topics that could be tackled in journalism education.

Our quantitative EJO/AJEN research confirms a prior quantitative study by Dr. Merle van Berkum (2024) from City University, London, now senior researcher at the Erich Brost Institute for International Journalism, indicating that a recurring challenge in climate change reporting across multiple countries is the lack of knowledge or training, followed closely by insufficient resources. In this study, journalists from Nigeria, South Africa, Germany, as well as the US all reported resource constraints as a significant barrier to comprehensive and progressive climate reporting. https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/32354/

Spotlight on African media: COP29 coverage in Uganda

The recently concluded COP29 meeting in Baku, provides an example of how relevant climate change is to politics in Africa and Europe. Not only do such events of political importance usually trigger peaks in the amount of climate change reporting (Brüggeman et al., 2018, p. 22). The coverage of the conference also reveals challenges media are grappling with when it comes to climate change reporting.

Taking Uganda as a case, COP29 received fair coverage in the local press, with 24 articles being published by the two leading dailies (New Vision and Daily Monitor) over the 12-day period. These included news articles as well as opinions and letters. The topics ranged from the climate financing debate to commentary explaining what Uganda’s priorities at the COP29 should be. The New Vision, which is also the government-owned newspaper, even introduced the COP29 beat.

Worth noting is that most of the articles (17) were sourced from international news agencies while only a handful (8) were written by the local journalists. Although one could argue that newsrooms in Africa, and in Uganda specifically cannot afford to send journalists to international events such as COP29, it also speaks to the observation that East African journalists struggle to report climate change (Oliver, 2023). According to Lidubwi and Wamwea (2023), this is evident in news reports that use generic stories and a global perspective as opposed to a local angle. In addition, the journalists lack access to climate change experts, but most importantly, they lack the necessary training to enable them to specialize in climate and environment reporting which is locally relevant.

A lack of “climate literacy”: Most pressing among most vulnerable

Academic analyses on climate change reporting in Africa confirm this impression. Various studies of climate change journalism and overall communication of the subject in Africa have revealed that the issue is poorly communicated by the media and other stakeholders such as governments, non-governmental organizations, the private sector and the scientific community. The environment beat has even been described by African journalists as “the poor people’s beat”, lacking not only financial support, but also recognition. (van Berkum, 2024, p. 169) All this leads to insufficient coverage of climate change. Untrained reporters covering scientifically dense topics could inadvertently draw incorrect conclusions. Climate change reporting requires not just basic resources but also advanced, “evocative storytelling methods” (ibid.) to effectively communicate complex scientific contexts.

As a result, public understanding of climate change can be below 50% in some countries. In May 2024 year, the African Climate Wire reported about a continental-scale study of climate change literacy rates across Africa which showed that public understanding of the subject was low at a mere 23% to 66% of the population across 33 African countries.

The report added that climate literacy was particularly insufficient for population groups who are already more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, such as the poor and women. Dr. Enoch Sithole, Executive Director of the Institute for Climate Change Communication in South Africa, says that “communication on the continent is very low, hence, public understanding is also very low. We have shocking data here in South Africa: only 12% of the South African population can comfortably talk about climate change. 52% say they haven’t heard about climate change,” according to an unpublished study of the Human Science Research Council (HSRC, 2022).

The low literacy levels are largely blamed on inadequate media coverage of climate change. Recent studies, such as (Sithole, 2023), have found that the coverage is frequently dominated by climate disasters, conferences and the releasing of scientific reports, instead of local stories of the day-to-day experiences of communities. While any reporting on climate change should be welcome, reporting on climate disasters is not very helpful to communities since it’s after the fact. Climate conferences tend to discuss top-end climate policy issues that do not attract much attention from ordinary people. Reporting on the releasing of scientific reports tends to generate copy that is usually above the ability of an ordinary person to relate. Sithole, who holds a PhD during which he focused on climate change reporting, says that “journalism needs to be able to report the climate story from their localities, from where they are, because that is when it makes sense. If we report about climate change as it happens in far-away places, it’s not going to resonate with local communities. And that is why you will hear people saying, ‘oh, stories about climate change don’t sell’. Yes, if you are sitting somewhere in the middle of Africa and you are constantly reporting about what happens in North America, in Northern Europe, people in Africa will not resonate with that.”

European journalism educators conference ahead in 2025

In Europe, journalism educators now start gearing up to the challenge. EJTA – the European Journalism Training Association – devotes its 2025 Teachers’ Training Conference in Rome to the topic. The conference will explore best practices to include environmental journalism into the curricula. “Environmental Journalism is a significant, stimulating and valuable subject of study, which lies at the intersection of politics, economics, science, nature and culture, between the individual and collective dimensions, and also between the local, regional and global levels”, states EJTA’s call for proposal, which is open until March 10.

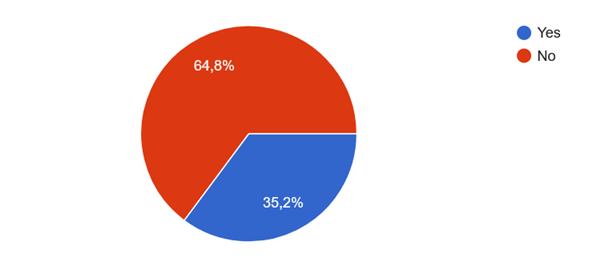

Do you think climate change reporting should be more widely included in journalism training in your country?

Complutense University in Madrid is one of the renowned European university-based media institutes who already offer optional modules on climate change coverage. Professor Alejandro Costa Escuredo goes even one step further when he says: “I believe it is essential that Environmental Journalism (it is the most accurate translation into English regarding the subject in Spain) should be an independent and mandatory subject. It should not be optional in any case. There are more and more spaces in the media that deal with climate change and, to do so, you must have knowledge of the subject.” Costa argues that “awareness must be a key element”, and warns that “currently, (intentional) misinformation about this matter is significant.” Complutense professors Dimitrina Semova and Alejandro Costa Escuredo have also collaborated in the conceptualization of creative tools to encourage “Green Citizenship” though digital artistic tools.

Perspectives for journalism education

When it comes to the question whether or not the topic should receive more attention in journalism education, an overwhelming majority of 95% of respondents in our pilot EJO/AJEN analysis said yes and this was true for both continents.

Thus, in Europe and Africa alike, journalism educators seem willing to explore the full dimension of the topic. According to Sithole, covering climate change is a cross-cutting topic for the media, and thus also for journalism educators. Many of them will be in need of training as well. “The educators need to educate themselves, also about climate change, (..) about the policies of climate change, because climate change is no longer just about the science, (…) how climate change links to economics, how it links to migration, how it links to crime, how it links to all other areas.” But Dr. Ngozi Omojunikanbi from University of Port Harcourt in Nigeria also warns that efforts on the side of educators might not be enough – at least in many African countries, where environmental issues are highly sensitive. “It requires also the political will of the government to include climate change in the journalism curriculum,” Omojunikanbi says.

Journalism schools are challenged to introduce climate change journalism teaching in their curriculums to empower journalists with the skills required to cover this complex subject – in a systematic and sustainable way.2 Otherwise, climate change will remain unknown to most Africans yet its impacts afflict pain and suffering daily; while a more solutions-oriented coverage including resilience strategies might be an option in European countries, where issues of climate change are reported by some media with an almost apocalyptic framing. The Constructive Institute has just started its “Constructive Climate Lens” project: “This is not to replace existing and often excellent climate reporting, but to supplement it in order to fight climate anxiety and news avoidance.” On its website, the institute argues further: “Experts have found out that climate change coverage which induces ‘fear, guilt and shame’ does not work for most people; they escape into denial. Journalism needs to reimagine the climate beat.”

[1] A total of 54 responses were received, 28 from 15 different African countries and 25 from 16 European countries. Both continents were thus almost equally represented in the survey. The responses were collected in September and October 2024.

[2] International support for environmental journalism in sub-Saharan Africa is nothing new. In the early 2000s, the Swedish Agency for International Development (Sida) initiated and funded the Regional Training Programme for Environmental Journalism and Communication in the East African Region (Jallov & Lwange-Ntale, 2006). They offered a scholarship to journalists from Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda to study for a postgraduate diploma at Makerere University at the Institute of Journalism and Communication. But perhaps, as Lidubwi and Wamwea (2023) note, such programmes were rather broad in scope and did not allow beneficiaries to specialise, even if climate change was not the main topic at the time.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies or positions of the EJO or the organisations with which they are affiliated.

If you liked this story, you may also be interested in: How a summer school is sowing seeds for strong, independent journalism in Ruissia

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.