War reporting is currently dominating many European newsrooms, but coverage has extended beyond the classic “war correspondent” sent to report first-hand from the war zone. Since Russia started attacking Ukraine, we have witnessed a variety of journalistic strategies to provide the public with orientation within the “messy business of war”, as it is described by media scholar Kevin Williams.

Learning from innovations that worked during the Covid pandemic, newsrooms have extensively used interactive infographics, direct engagement with the public, and fact-checking. And for the first time, podcasts are now a vital part of conflict reporting in many countries. In this overview, the EJO network provides snapshots of effective and creative media projects from across Europe.

Britain

‘Full Fact’ and ‘Ukrainecast’

As the UK’s demand for reliable information on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine increases, two providers stand out as sources of fact-checked and objective reports about the war: Full Fact and BBC’s Ukrainecast.

Intensifying UKs fact-checking efforts

In recent weeks fact-checking has become increasingly important. According to Euronews, before February 24th, a Russian mass disinformation campaign was created to frame Ukraine as aggressors in order to legitimise an invasion.

Full Fact aims to tackle this kind of disinformation. It is a registered charity founded in 2009 and based in London, and its team of independent fact-checkers has made it their mission to check and correct claims in news stories and viral content on social media. One of their commandments is to work impartially and to be politically neutral.

This is not the first time the platform has featured Ukraine, but it appears to have intensified its focus on the country, currently publishing daily fact checks about the war. This includes challenging viral videos, such as the one of an explosion that is supposed to have taken place in Ukraine – but was actually first found online after the Beirut port explosion in 2020.

Analysis and overview

Ukrainecast, the other notable UK-based reporting tool, is a podcast launched by public broadcaster BBC at the start of the invasion. It offers audiences a compact overview of the news as well as an analysis of current events and is particularly important in the context of the blocking of BBC‘s websites in Russia.

The BBC publishes a single episode every day, offering a counter design to the rapid news flow usually available online. The idea is to give journalists and civilians on the ground in Ukraine a voice and to answer questions that may be on people’s minds but may not be covered in the regular news cycle.

It tackles important questions. Why did Putin start this war? What is it like for those with family in Ukraine? How are people in Ukraine fighting back? Which cities are under attack?

Czech Republic

Focus on multimedia storytelling

Czech media has been actively broadcasting the war in Ukraine. In fact, almost the entire media space, perhaps with the exception of the sports section, has directed all its attention towards the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Readers, listeners, and viewers are getting up-to-the-minute updates from timelines, infographics, maps, data visualisation, and live streams from Ukraine on the war and its knock-on effects such as the refugee situation and the economic impact on Ukraine, Russia, the Czechia, and Europe.

The internet daily Aktuálně.cz uses an online feed with a multimedia storytelling format. They cleverly organise and connect all the content related to the war in Ukraine in one place. This gives their audience easy access to different media, such as videos, podcasts, and photos.

Some Czech media also offer coverage on the Ukraine war in a foreign language. Public broadcaster, Czech Radio, has launched an internet stream that broadcasts Ukrainian public radio. The transmission aims to ensure the availability of information about the war for refugees and Ukrainians living in the Czech Republic.

Czech Radio is also preparing a podcast entitled ‘News for Ukrainians in the Czech Republic‘, to provide practical information for people who have fled to the territory. In Ukraine, the podcast will be published by Radio Prague International.

In print, online newspaper Novinky.cz publishes a daily summary of the most important events in Ukraine with a link to this coverage placed prominently on its home page. Reported in Russian, the summaries are intended primarily for audiences from the Russian Federation. As stated on this site, the goal is “to provide much-needed transparency in the conflict in Ukraine” through “an uncensored daily digest of currently unfolding events”.

Germany

Katapult and Correctiv’s ‘sanctions tracker’

Katapult

In Germany, much of the content on the war in Ukraine is produced by Katapult, a newsroom in a small north-eastern town called Greifswald. The magazine, which specialises in infographics and maps, has poured its resources into covering the war in Ukraine, offering insight and analysis.

The outlet addresses important questions. Which parts of Ukraine are occupied? What is Germany’s official capacity to take refugees? And, how many people have been detained in Russian cities for taking part in anti-war protests?

But, perhaps its most remarkable contribution is the decision of several of its staff members to give up part of their salary to finance and equip up to twenty Ukraine-based journalists, who report for Katapult from war zones, from hiding places, or while fleeing.

Every day Katapult produces new graphics with the blue and yellow of the Ukraine flag as the dominant colours. One infographic shows how the number of sanctions against Russia has increased over time. It is based on another notable media project: the ‘sanctions tracker’ set up by Correctiv – a foundation-funded investigative journalism organisation.

Correctiv

Correctiv runs a website dedicated to tracking the sanctions that have been imposed against Russia, using data from OpenSanctions. It provides this information in the form of infographics and a searchable table. The website also offers background details on the targets of the sanctions, whether it is an individual such as Artur Matthias Warnig, manager of the Nord Stream gas project, or a company such as Sberbank – Russia’s largest bank. In their coverage, the organisation reiterates the message that sanctions are currently the West’s most important weapons while, at the same, questioning their effectiveness.

These two examples stick out in Germany’s media landscape with its dual public service and commercial broadcasting system and its deeply rooted tradition of having a handful of leading newspapers. As relatively young, small, and not-for-profit media start-ups, Katapult and Correctiv are certainly comparatively agile and able to implement ideas more quickly than many of their established competitors. That being said, one could question whether initiatives such as staff members giving up part of their salary is really the most employee-friendly approach to financing journalism, given that Katapult does have financial reserves.

Overall, the ability to adapt quickly is something that has become increasingly important for Germany’s media sector as it covers the war in Ukraine, considering that with recent developments such as the Kremlin’s newly introduced “fake news” law, Germany’s public service broadcasters ARD and ZDF have decided to temporarily pause reporting from inside Russia.

Italy

‘Stories’: the daily podcast from Ukraine

Data shows that some nine million Italians listened to at least one podcast in June 2021 and that the format is definitely gaining momentum in the country. The Italian podcasts market is active, with various journalists launching their own audio projects, focusing on daily press reviews or slow journalism with longer reports and in-depth investigations.

One of these is ‘Stories’, a daily podcast on international news produced by Chora Media, which is a media company founded in 2020 and entirely focused on podcasts and audio projects. Stories’ author is Italian foreign affairs journalist Cecilia Sala. At the start of the conflict, Sala traveled to Ukraine and began producing the podcast from the frontline. Since then, she has produced a dozen episodes from Kyiv and other conflict areas.

Sober, accurate, and emotional

Sala’s podcast offers insights and updates about the major events surrounding the conflicts, mixing them with first-person reporting, the voices of Ukrainian witnesses, and behind-the-scenes explainers. In one episode, she reported from the bunker below the Okhmadyt children’s cancer hospital in Ukraine’s capital, where the patients have been moved in the fallout of the Russian attack, giving audiences an insight into some of the extremely challenging situations in the country.

In another episode, Sala covered the shelling of Chernihiv through the experience of fighting volunteer Denis, who is in his mid-twenties. Overall, the Stories podcast offers a sober and accurate yet emotional account from the frontline and represents an evolution in how Italian media are reporting the conflict. It also demonstrates the potential of podcasts in journalism.

Latvia

Special editions and news in Ukrainian

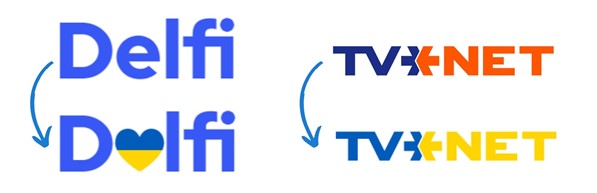

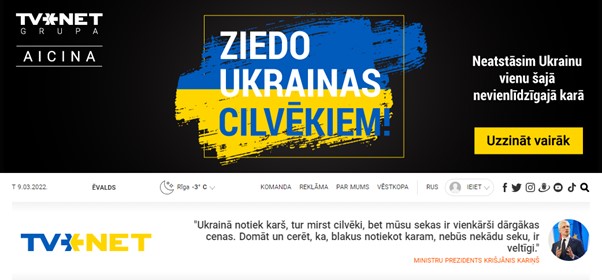

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took over Latvia’s media landscape instantly, with all media outlets working flat out to cover events in Ukraine. Some have gone as far as changing their logos to express their support for Ukraine. Online media have created special sections on their platforms and introduced special ‘skins’ and headers for their portals. TV stations have provided additional news editions, discussion broadcasts, and live streams. And magazines have developed strong covers.

Traditional electronic media has stood out on the overall news scene, especially Latvia’s public broadcasters, the Latvijas Televīzija (Latvian Television) and Latvijas Radio (Latvian Radio). They have been especially active, timely, and to some extent, even innovative in their coverage of the war in Ukraine.

Traditional electronic media has stood out on the overall news scene, especially Latvia’s public broadcasters, the Latvijas Televīzija (Latvian Television) and Latvijas Radio (Latvian Radio). They have been especially active, timely, and to some extent, even innovative in their coverage of the war in Ukraine.  For example, by February 24, Latvijas Televīzija had already changed its visual design for their studios, and two weeks later, it was still using the colours of the Ukrainian flag.

For example, by February 24, Latvijas Televīzija had already changed its visual design for their studios, and two weeks later, it was still using the colours of the Ukrainian flag.

From the first days of Russia’s invasion, they introduced interactive warfare maps in their news programs to show the geography of military actions – something this channel has never done before.

But public broadcasters didn’t limit their efforts to just the visual element of their coverage; they also provided very timely special news editions, numerous experts‘ discussion programs, and live broadcasts from their correspondents in Ukraine. They covered important media events such as the concert Ukrainas brīvībai (For the Freedom of Ukraine) on February 25, which took place in a park across the street from the Russian Embassy in Riga and was attended by thousands of people. Broadcasted by Latvian television, it was co-live-streamed on commercial television channel TV3. The short version of this support action was also available on ARTE, the European culture TV channel’s online version.

The weekly investigative journalism program ‘Nothing Personal‘ on TV3 gained much attention on social media after one of the anchors wore a sweatshirt with the Russian version of the powerful message “Russian warship, go f*ck yourself”. Ukraine Snake Island defenders used this message just days before when Russia’s military forces asked them to lay down their weapons, and it became an international meme in different languages.

The weekly investigative journalism program ‘Nothing Personal‘ on TV3 gained much attention on social media after one of the anchors wore a sweatshirt with the Russian version of the powerful message “Russian warship, go f*ck yourself”. Ukraine Snake Island defenders used this message just days before when Russia’s military forces asked them to lay down their weapons, and it became an international meme in different languages.

On radio, Latvijas Radio’s minority languages program, LR4, which broadcasts mainly in Russian, promptly supplemented its program with Ukrainian public radio news in the Ukrainian language, twice a day.

And in print, Weekly news magazine Ir (It is), a week after the start of Russia’s invasion, published a supportive cover in Ukrainian stating “Слава Україні!” (Glory to Ukraine).

And in print, Weekly news magazine Ir (It is), a week after the start of Russia’s invasion, published a supportive cover in Ukrainian stating “Слава Україні!” (Glory to Ukraine).

A week later, they followed up with another compelling cover with a strong visual message and transformed it into a downloadable sign, “You reap what you sow,” for public rallies. The Pauls Stradiņš Medicine History Museum, located directly opposite the Russian Embassy in Riga, even created a large-scale poster version, which they hung on the wall of their building.

Poland

Content in Ukrainian and information for refugees

Since February 24th, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been the number one topic in all Polish media outlets, at both local and national levels. This is primarily because of the geographic proximity of the conflict and the visibly direct consequences of the war for Poland, especially in terms of the huge influx of Ukrainian refugees to virtually all regions of the country – more than a million by the end of the first week of March.

This level of coverage was mainly made possible by Polish media’s access to the refugees in the country, and because of the unprecedented number of Polish correspondents present in Ukraine during the conflict, with all big media outlets having journalists in either in Kyiv, Lviv at the Polish-Ukrainian border, or on the frontline.

From the very beginning of the invasion and following the refugee crisis, some of the biggest media organisations in Poland decided to publish key content, not only in Polish, but also in Ukrainian. Numerous outlets also opened, on their own platforms, free access to Ukrainian TV or radio channels.

Updates for refugees

The biggest online news portal, Onet, decided to add articles in Ukrainian to their homepage. These include important updates related to refugees, providing Ukrainians arriving in Poland with information about different aspects of their stay such as forms of support, regulations etc. In fact, they have created a special microsite, Onet Ukraine, with detailed and tailored information.

Public service Radio 1 also provides updated information in Ukrainian on their website. A section with news in Ukrainian is available through one click from their homepage. Additionally, news in Ukrainian is broadcasted three times a day – 10:06, 14:06 and 17:06.

Furthermore, Ukrainian journalists have been hired in Polish newsrooms, not only as a token of support, but also to make the coverage more reliable and accurate.

Switzerland

Focus on audience engagement

In Switzerland, there was a focus on communication with audiences, expert analysis as well as ensuring real-time updates through tools that had been popularised during the pandemic, such as maps and infographics.

Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen

One notable service is the ‘News Plus’ podcast, produced by Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (SRF) – the German-speaking unit of the Swiss public service media SRG SSR. What makes this podcast unique is its connection with its audience, in particular with the public broadcaster’s online community.

This strong focus on audience engagement is demonstrated by the communication channels between the editors and the audience, which include emails and WhatsApp messages; as well as the choice of complex and sensitive topics such as “Russian women, discrimination and propaganda”, “Why humanitarian corridors are so difficult to establish”, “The social media war from a Ukrainian perspective”, and “The role of the cyber-war in Ukraine”.

Furthermore, the podcast takes time to explain the issues, using a range of perspectives from journalists, correspondents from the frontline, academics, as well as witnesses of the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine, Russia, and Switzerland.

Radio Télévision Suisse

Some newsrooms have used existing formats to host special editions. For example, all the television programs of Radio Télévision Suisse (RTS) – the Swiss public service radio and television – are collaborating on a show dedicated to the war in Ukraine. In preparation for this program, RTS used its social networks to collect questions from the public, especially relating to humanitarian aid.

The RTS daily radio program Forum has used a similar approach. This platform, which focuses on news and debate, has devoted one of its evenings to a dialogue with its audiences. According to a journalist from Forum, the special edition was in response to numerous enquiries from their audience about the war in Ukraine.

Heidi.news

Another noteworthy outlet is Heidi.news, which has launched a ‘special week of experts‘ program, designed to provide a break from the common minute-by-minute, uninterrupted flow of information since the beginning of this crisis. In their own words, with this special series, Heidi.news aims to “broaden horizons, to question different fields…. Because in the time of the Covid-19 pandemic as well as in front of a war that could become uncontrolled, the world… needs its scientists and intellectuals”.

24 heures and Tribune de Genève

Generally, many newsrooms revived the use of tools and features which had already begun to take on more and more importance during the Covid-19 crisis. A good example of this is 24 heures’ and Tribune de Genève’s use of maps, infographics, and data visualisation. This is illustrated in the article, In this summary of the first two weeks of the Russian invasion in Ukraine, which reports the latest movements of the Russian army, the material support of the European countries, and the sanctions that have been taken against Russia.

Snapshot by the EJO Network

Project coordinator and author:

Ines Drefs, Erich-Brost-Institut, Dortmund, EJO Germany

Editor:

Natricia Duncan, City University of London, EJO United Kingdom

Authors:

Olivia Samnick, EJO Fellow, EJO United Kingdom

Colin Porlezza, Università della Svizzera italiana, EJO Switzerland (Italian)

Philip Di Salvo, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), EJO Switzerland (Italian)

Sandra Lábová, Charles University, Prague, EJO Czech Republic

Michał Kuś and Adam Szynol, University of Wrocław, EJO Poland

Cécile Détraz, Université de Neuchâtel, EJO Switzerland (French)

Līga Ozoliņa and Ainārs Dimants, Riga Stradiņš University, EJO Latvia

Images: Shutterstock and photos of European press supplied by EJO editors.

Opinions expressed on this website are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views, policies, or positions of the EJO or the organisations with which they are affiliated.

Tags: Podcasting, Reporting war in Ukraine, Russia, Ukraine