For a long time, Iceland was seen as a shining example of press freedom – too good to be true, perhaps. But more recently, the country’s politicians have been attempting to influence the media. The latest example came right from the top when Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, Prime Minister at the time, tried to suppress a television interview about his ownership of an offshore firm in Panama. The attempt failed and Gunnlaugsson was eventually forced to resign.

The now famous interview shows Gunnlaugsson begin to stammer as a Swedish journalist asks him about the offshore company, Wintris. Shortly afterwards he leaves the room, denying all allegations. To make matters worse, Gunnlaugsson’s assistant then called the TV station to try to stop the interview being broadcast.

Politicians and Iceland’s public service broadcaster

Gunnlaugsson’s attempted interference isn’t the first by Icelandic politicians: many have complained in parliament that RUV, the country’s public service broadcaster, is biased. In August 2013, Vigdis Hauksdóttir, a member of Gunnlaugsson’s Progressive Party and chairman of the Parliament’s Budget Committee, issued a thinly-veiled threat. “I think an unnatural amount of money goes to RUV. Especially when they don’t do a better job at reporting the news…” she said. Months later, in December 2013, RUV’s budget, which is directly controlled by government, was reduced by 20%.

The budget cut led to complaints by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and forced RUV to cut programmes and reduce staff, for example reducing an already sparse network of foreign correspondents to zero. The broadcaster expects further cuts to its service in the foreseeable future.

Valgerdur Anna Jóhannsdóttir, a media academic at the University of Iceland, said she is sure “the constant criticism has at least a potentially deterrent effect on journalists”. She added there is less distance between politics and public service broadcaster in Iceland than in other Nordic countries.

Private media companies: mouthpieces of the powerful

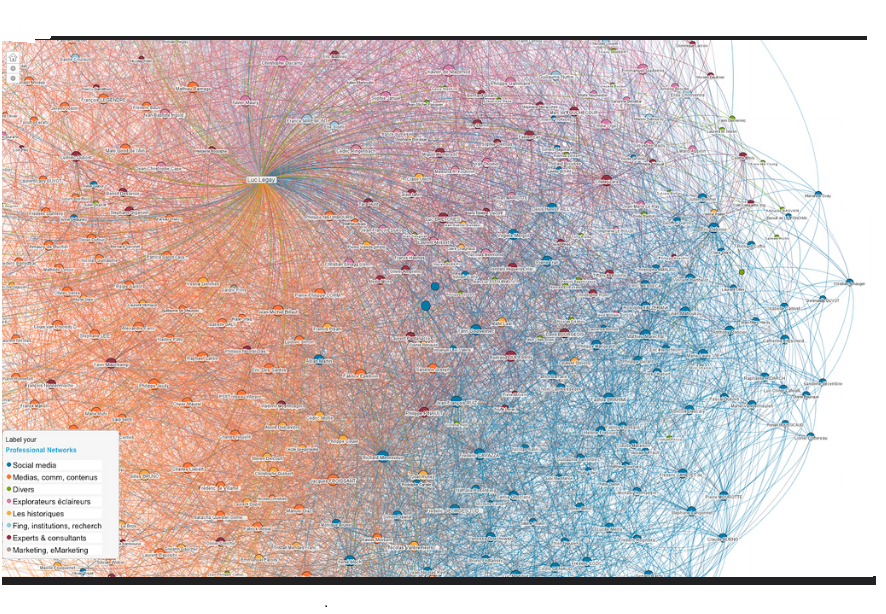

Many of Iceland’s established private media companies are owned or edited by politicians or powerful business figures and are rumoured to serve particular interests. As a result public trust in the media has significantly declined in recent years.

RUV’s long-standing rival is the daily newspaper Morgunbladid. Often accused of bias by critics, the newspaper can be seen as an example both of the problems of Icelandic society in general, and of the media landscape in particular. Morgunbladid’s investors are part of the country’s fishing industry. They fear that a reform-oriented government might threaten their wealth, by imposing a quota system. “This attitude is evident in all of their op-ed articles,” according to Jóhannsdóttir.

The newspaper’s editor-in-chief, David Oddsson, is highly controversial. Oddsson, a member of the Independence Party, was Prime Minister from 1991 to 2003, then briefly Foreign Minister, before he became director of the Central Bank in 2005. It was during his time as Prime Minister that the privatization of the bank system took place, in a manner which laid the foundations of the financial bubble. Critics say his job as head of the Central Bank was to prevent the bubble bursting, but he failed in this task.

Oddsson made TIME Magazine’s list of the “25 People to Blame for the Financial Crisis”. It is profoundly problematic that he has become one of the most powerful media personalities of the country after all that. For years, he used the newspaper to re-write history. “His version of events has received a lot of coverage in the newspaper,” Jóhannsdóttir said. Oddsson ran for president earlier this year [June 2016] and during his campaign the newspaper led by him, and supportive of him was distributed for free. However, with fewer than 14% of the votes, he only came fourth in the vote.

Trust in Iceland’s media is declining

According to a survey done by the polling firm MMR, trust in established Icelandic media has declined since the 2008 financial crisis. Morgunbladid has seen one of the biggest falls. While 60 percent of its readers declared their trust in the newspaper at the end of 2008, only about 40 percent still trusted it in 2014 (more recent data is not available). RUV lost seven percent, going from 77 percent to just over 70 percent in the same amount of time.

Another big player is the privately-owned 365 media group, with its newspapers, TV and radio stations. It is controlled by Ingibjörg Pálmadóttir. Until the financial crisis Pálmadóttir and her husband, the investor Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, were among the most important investors in Iceland. Jóhannesson held shares in the bank Glitnir and also expanded through additional purchases abroad (e.g. House of Fraser, Karen Millen). In 2002, 365 media group took control of the newspaper Fréttabladid, a free daily tabloid newspaper which has the highest circulation in Iceland. This made Jóhannesson Iceland’s most powerful man, according to the politics professor and Oddsson-confidant, Hannes Hólmsteinn Gissuarsson.

The tabloid newspaper, DV, is now owned by Björn Ingi Hrafnsson, a former Progressive Party politician (currently in a government coalition with Oddsson’s Independence Party).

Apart from the big media companies, there are also a few smaller online-media outlets. Websites like Kjarninn.is, Stundin.is, and Kvennabladid.is operate more independently than the big commercial outlets. Their reach is smaller but nevertheless they are noticed – not least because internet use in Iceland is very common, including among older people.

The role of foreign media

The interview about the Panama accounts that ultimately forced the Prime Minister to resign was recorded for Swedish television SVT and was based on the research of the international Panama Papers research group. Even before the interview was broadcast, the prime minister’s wife, Anna Sigurlaug Pálsdóttir, had conceded the existence of such offshore accounts. However, when foreign media began covering the story it turned into a huge scandal.

Whilst the foreign press can act as a corrective, one problem is that many stories about Iceland published in international media are superficial and stereotypical, with stories such as one about the spokesperson for elves getting more hits and traffic than investigative stories. That also might be due to the fact that only a few foreign journalists really know Iceland and have a strong network there.

Press ranking

Powerful politicians, business interests and cuts in public funding have all helped tarnish Iceland’s pristine image. So it’s unsurprising that Iceland drops behind the other Nordic countries in the Freedom of the Press Ranking by Reporters without Borders. In contrast to Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, which are ranked at the top along with Germany and a handful of other countries, Iceland is placed in the next best category, dubbed only “satisfactory”. The United States, South Africa, Poland, Romania, and France share that category.

Anyone who takes a deeper look at the Icelandic media landscape might ask whether the situation actually is “satisfactory” or if it might be a bit more complicated than Reporters without Borders describes.

Image: screen shot, SVT and Reykjavick Media / Guardian website

Author Photo: Kristian Ridder-Nielsen

This article first appeared on the German EJO as part of a longer article. It has been shortened for this site and translated from the original by Lena Christin Ohm.

Tags: Censorship, David Oddsson, Iceland, panama papers, Press freedom, Press Freedom Index, Reporters without Borders, RUV, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, SVT