Message, 3/2009

In the mid-90’s, Mark Willes introduced controversial structures to rescue the Los Angeles Times, yet in the end arduous opposition brought him down. Had his strategy been implemented, however, today’s crisis may not be as grave.

In the mid-90’s, Mark Willes introduced controversial structures to rescue the Los Angeles Times, yet in the end arduous opposition brought him down. Had his strategy been implemented, however, today’s crisis may not be as grave.

The days when local newspapers enjoyed regional monopolies are long gone, largely due to the ever-expanding Internet and rising competition. Punishment for overlooking the desires of readers is much more severe nowadays, according to online journalism expert Pablo Boczkowski. Journalists may no longer dismiss their publics’ interests without severe punishment.

Market research became vital in the media business, though journalists and publishers in both Europe and America took far too long to catch on. Publishers were slow to zero in on market research because they generally held unrivaled positions, and those who hold monopolies show little interest for clients, while journalists simply didn’t see market research as something that would augment their profession. Furthermore, experienced editors reflexively view marketing and PR specialists as members of the opposing team. Accepting PR and marketing experts as indispensable facilitators of brand and service promotion remains a difficult leaf to turn.

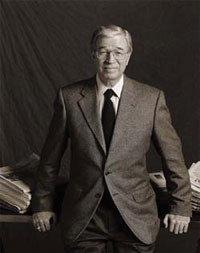

From cereal producer to publishing boss

Among the first to attempt to pioneer this concept is Mark Willes. Willes was appointed CEO of the Times Mirror empire in 1995, leaving his post with cereal producer General Mills just as things began to look grim for the media group. Sales of the group’s main paper, the Los Angeles Times, crashed by 19 percent over the previous four years and threatened to fall under the magical one million mark. Prospects of advertising, which comprised 80 to 85 percent of most U.S. newspapers’ revenue, were weakening as well. Southern California’s armament industry was in a deep crisis after the end of the Cold War and acquisitions in retail trade added to difficulties in finding advertisers.

Mark Willes’ entrance in office led to a cultural revolution where market research was intensified and the editorial staff and the advertising sector were forced to work hand-in-hand. Marketing specialists informed about the editorial planning were assigned to each department of the newsroom. They were supposed to raise more targeted advertising and to improve the company’s marketing strategy. Without having any editorial role, they were also asked to market the editorial content of the newspaper more professionally.

This strategy is best illustrated in the business section, for it was the first to prove that the new concept worked. Collaboration between the editor and the company’s new marketing star, 32-year-old Kelly Ann Sole, succeeded in gaining new readers and 40 percent more advertising for the Tuesday business special. The relaunched business section “Wall Street California” focused more on readers’ finance than previously. Willes, generally known for his drastic economies, provided the department with 11 additional journalists.

Another revolutionary Willes move was his creation of a system that would continuously evaluate the performance of each newspaper section. Willes was clever enough to realize that not each section could be profitable, and he insisted on following readership developments and advertising income for each section and local edition. Previously, the newspaper’s performance was only examined as an entity; now, under Willes’ leadership, each department or local edition evolved into a profit center.

The stock market soars, as do critics

Resonance was strong and ambivalent, and Wall Street loved it. In the media, Willes was subject to more malice and riducule than any publisher before, and the choir of disproving critics was led by the crème de la crème of American journalism. A whole range of celebrities from the media world, among them chief editors of the Washington Post and the New York Times, Ben Bradlee and Max Frankel, as well as famous leftist journalism critic, Ben Bagdikian, were willing to adamantly attack Willes.

A chief fear was that journalism would become dictated by the results of opinion polls, or even worse, that it would soon be guided by advertisement experts. Thus, the sacrosanct wall separating the editing from the advertising, would crumble.

Willes was not completely inculpable for his scandalization. He liked to provoke, for example announcing that he would like to blow up the wall with a bazooka. Indeed, he believed that such institutionalized arrangements were unnecessary and insisted the only thing that counted was the integrity of the working staff. In the Columbia Journalism Review he was quoted suggesting that those who got in his way should leave and instead work at clogging the innovations of his competitors.

Willes the “cereal killer”

Contrary of most of his counterparts, Willes had a strategy, which most of them lacked at the time and still do. Daily papers had to fight against competition from booming special-interest journals in order to keep a readership interested in a large spectrum of information. Newspapers neglected marketing and advertising, especially when it came to appealing to different ethnic groups. At that time already, 41 percent of Angelinos were of Hispanic origin and the Asian population was well represented as well.

None of Willes’ critics could prove that Willes compromised his editorial staff. In fact, the most severe criticism of Willes was actually published in the Los Angeles Times itself. Former media editor David Shaw castigated Willes in print, writing that skeptics at the LAT and from all over the branch feared that the structures he put in place would inevitably allow editors of lower stature to be overlooked.

Even the LAT’s arch-rival from the East coast, the New York Times, later acknowledged that fears they had of seeing writers’ integrity harmed by Willes’ tactics had faded. The paper believed that Willes’ practices would lead to his failure in implementing ideas. During his two years as boss of the publishing group, two-thirds of leading reporters and collaborators were either asked to leave or left independently. Willes considered such internal conflicts normal.

Yet Willes displayed humor through the ordeal. During a speech at a conference of U.S. newspaper editors in San Francisco, he listed the different nicknames he’d been awarded by the press. Perhaps the most famous was “Cereal Killer,” a refernce to his human resource management and to his past in the food industry. Runners-up included “Captain Crunch” and “Corporate El Nino” which accurately characterized the ways in which he disturbed a lethargic media empire.

Unjustified media turmoil

Willes’ undoing came when he passed a sponsorship contract with the Staples Center, a new sport arena in Los Angeles, without informing his editors. The contract ensured that advertising revenues of a special supplement for the opening of the Staples Center would be split between the newspaper and the sporting events’ organizer. The L.A. Times benefitted from exclusive rights to newspaper sales within the arena and upper-tier Times Mirror personnel received preferences for ticket purchases. However, the sale of advertising for the supplement did not go as well as anticipated. At this point, Willes’ subordinates suggested to devote, instead of the supplement, a special edition of the L.A. Times’ magazine to the sporting venue without informing the editors about the contract – a decision that ultimately led to the final scandalization of Willes.

Looking back at the affair, much of the media turmoil appears unjustified. Indeed, to this day, no media expert has been able to explain what was so disreputable in the act of sponsoring a third party without informing the editors. There was certainly no attempt to influence the editing, because the editors didn’t know about the contract. The more media journalism established itself in the U.S., the more often newspaper managers and media entrepreneurs became victims of scandalous news coverage once reserved for stars, politicians and CEO’s.

Out of dozens of articles published about the L.A. Times in the most respected newspapers and the specialist publications, none credited the new organization structure for what it really was: the decentralization of a rampant bureaucracy. A bureaucracy, according to LAT columnist Kathy Kristof, that not even the soviet politburo could compete with.

Discredited throughout the branch

The downfall of the Los Angeles Times’ only grew worse after Willes’ departure. Looking back, Willes should be exonerated. What he attempted to implement was innovative and would have helped the newspaper industry make its way out of the crisis. Market research, daily feedback from readership and targeted ad marketing respect editorial plans without influencing the work of editorial departments. Such clever concepts encourage the production of quality journalism in a problematic financial climate.

Had Willes’ tactics been replicated, perhaps America’s mainstream media would be targeting the public’s needs and wishes as they’re failing to do today. Journalists who followed the herd in scandalizing Willes rather than viewing the situation rationally delivered bullets to their own knees. As his innovative measures were discredited throughout the branch, newspapers sunk deeper and deeper into the crisis.

Translation by Patrick Wilson

Image courtesy of Flickr – Brad Slade

Tags: Los Angeles Times, Mark Willes, Market research, PR