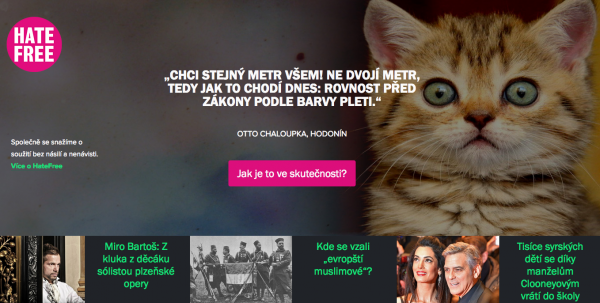

Prima TV ‘reported’ a Franciscan monk swimming, fully clothed, as part of a fake news story that alleged burkinis are a ‘health hazard’.

Freedom to publish on the internet and the expansion of social networks have brought unprecedented communication possibilities to the Czech Republic, as well as an influx of fake news, hoaxes, and disinformation.

Campaigners draw attention to several hoaxes being spread every week, on social media, anti-immigration and pro-Russian websites. Even Prima Television, the country’s third largest television station, has been accused of deliberately manipulating the news to represent refugees and Islam as a “threat”. Although the impact of such disinformation upon public opinion is unknown, government and private initiatives have recently been launched to improve media literacy and increase public awareness.

Taking media education to schools

Fake news and disinformation were the main topics at the Media Education Week 2017, a recent project organised by Czech NGO Člověk v tísni (People in Need). Over a six week period, seminars dedicated to media education, debates with journalists and media professionals, and screenings of thematic documentary movies were offered to primary and secondary schools across the country.

As part of Media Education Week, school students had the opportunity to listen to expert opinions and meet leading Czech journalists. The main points of the discussions were how to recognise fake news and misinformation. Topics such as: the core characteristics of fake news; how to oppose disinformation and the role of social media in spreading fake news were addressed.

A new framework is being developed for the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessments (PISA). It will examine the ability of 15-year-old students to interact in an interconnected global world and will assess media literacy. The Czech Republic did not join the project for financial reasons. However, according to reports on Aktuálně.cz, the Czech School Inspectorate is preparing national surveys to measure the level of media literacy of Czech pupils and students, including the ability to recognise misinformation and false reports.

The government’s role

The Czech government has also launched a number of initiatives aimed at fighting fake news and disinformation online.

HateFree Culture, set up in 2014 to fight racism and xenophobia in the Czech Republic, was the first of these activities. Other quickly followed. At the beginning of 2017, the Centre for Combating Terrorism and Hybrid Threats was established by the Ministry of Interior. Its primary activity is to dispel disinformation that threatens national security.

Private companies and fake news

Private actors are also fighting false messages. Several independent Czech news sites, such as Hlídacípes.org, Hoax.cz, Demagog.cz or Manipulátoři.cz, regularly update the list of websites involved in spreading hoaxes and fake reports. Other examples of sites that debunk fake news include Neovlivní.cz, headed by investigative journalist Sabina Slonková. Neovlivni.cz focuses primarily on Russian propaganda.

Technology companies such as Google and Facebook have declared they will combat false messages. However, they alone cannot guarantee the accuracy of the news required by journalists in the traditional media.

Advertising revenue and fake news

Many of the sites accused of spreading disinformation and false news are funded from advertising revenue. The companies that advertise on these websites often unknowingly support them.

Some companies are taking steps to end advertising links with sites associated with fake news. For example Vodafone, the world’s second-largest mobile operator, recently issued a statement vowing to block any ads displaying hate and fake news.

Other companies are less sure about how to manage the problem. At the beginning of August 2017, Seznam.cz, the popular Czech searching engine, caused confusion by issuing mixed messages about how it planned to deal with fake news.

Several news sites reported that Seznam.cz would refuse to advertise on web sites that present opinion as news, feature anonymous authors or publish false or inaccurate information. These reports were confirmed by Seznam’s spokesperson, Táňa Lálová. However, within a week, Seznam appeared to back down. Its executive director Michal Feix said the management did not know about these plans and that “the board of directors and the owner do not want us [Seznam.cz] to determine the objectivity and truthfulness of the news sites that are included in our advertising network.”

Other Czech companies are becoming aware of the issue, although slowly. Martin Neuschl, a digital analyst, said many are unsure how to identify and manage their commercial relationship with disinformation sites and they are often unaware of any links with such sites. “Company managers are usually surprised when I point out their ads are being displayed on notorious disinformation sites, such as ParlamentníListy.cz (Parliament Papers). Subsequently, most of them take steps to ban the promotion of their brands on this or similar websites. The problem is not that they would not be willing to take necessary measures. However, disinformation sites and possible support of them through advertisement remains under many companies’ distinctive ability,” Neuschl said.

Sleeping Giants, a Czech-based Twitter group established to notify companies advertising on fake news sites

Last year, Twitter group Sleeping Giants was formed in the Czech Republic. It identifies companies advertising on disinformation sites and alerts them. A similar project, Konspiratori.sk, is based in neighbouring Slovakia. Konspiratori was founded by a digital agency that manages a database of misleading sites. Its aim is to discourage potential advertisers that, knowingly or not, support disinformation websites. The website also offers a detail description of the mechanism for classifying particular news portals as misleading. Based on predefined and publicly available rules, the site’s board of experts determines which sites will be included in databases.

Can we detect manipulation?

Lucie Šťastná from the Institute of Communication Studies and Journalism of Charles University in Prague points out the media education must distinguish fake news and disinformation. “These two terms might overlap and signify similar issues. However, we should recognise the intention: why the false news or disinformation is being spread. The aim of disinformation is to deceive the recipient, especially for political reasons. The motivation behind false messages and hoaxes is different. These are usually intended to attract attention to the news site that spreads them, often for advertising purposes,” Šťastná explained.

There has been little research conducted in the Czech Republic that would examine how the false messages and disinformation are being spread and perceived. Last year, the non-profit organization Think-tank Evropské hodnoty (European Values) commissioned research that examined public belief in misinformation propagated by “pro-Kremlin” media. According to its finding, a quarter of Czechs believes the fake news and disinformation.

Prima TV ‘reported’ a Franciscan monk swimming, fully clothed, as part of a fake news story. It alleged burkinis are a ‘health hazard’.

The public is more likely to believe fake news if it is reported on mainstream media. The country’s third largest television channel, FTV Prima, allegedly ordered staff to pursue a news agenda that portrayed refugees as a “threat”. The channel has also been accused of spreading manipulated information on its main news.

One recent Prima news item discussed social media photographs that showed Muslim women, wearing burkinis, swimming in a public swimming pool. The report questioned whether the women’s clothing presented a health hazard. A reporter was shown bathing in a Franciscan monk’s robe (above) and subsequently being questioned by lifeguards.

Tags: Czech Republic, disinformation, fake news, Hate Speech, Hate Speech Culture, Journalism, media, Media Literacy, PISA, PrimaTV, Sleeping Giants, Social media