- 137Shares

- Facebook72

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn48

- E-mail1

- Buffer8

- WhatsApp1

The 2017 Digital News Report, based on a YouGov survey of 70,000 people in 36 countries, finds trust in media is low. Yet more people are paying for online news – especially in the US.

Audiences are dissatisfied with the quality of news and comment generally, and on social media in particular, the sixth Digital News Report reveals.

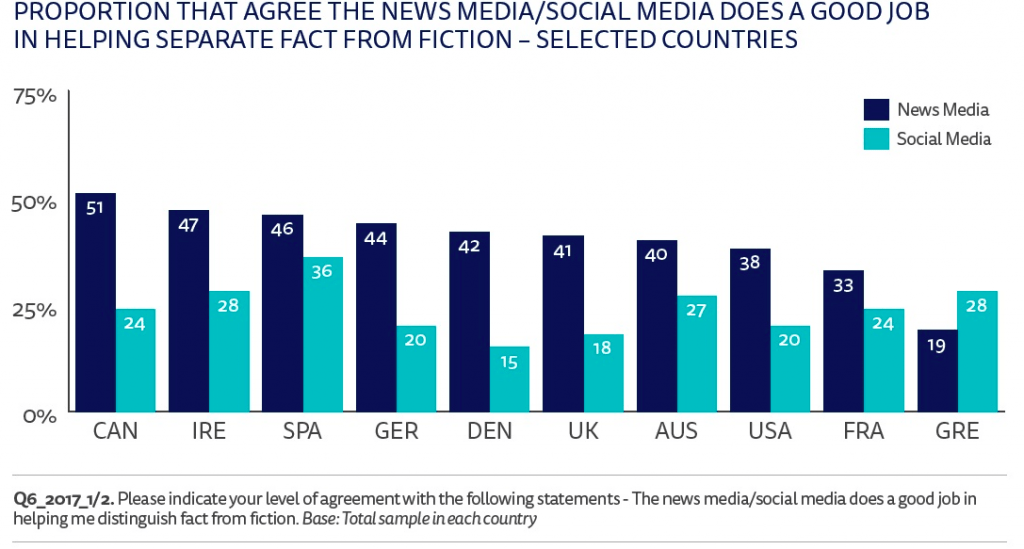

The report, from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, is based on an online survey of 70,000 people in 36 countries. It found that although over half of respondents (54%) use social media as a source of news, only a quarter (24%) think social media does a good job in separating fact from fiction, compared to 40% for the news media.

In countries like the US (20%/38%), and the UK (18%/41%), people are twice as likely to trust the news media. Only in Greece do more people think social media is doing a better job, primarily because they have very low confidence in news media (28%/19%).

Trust in the media and political bias

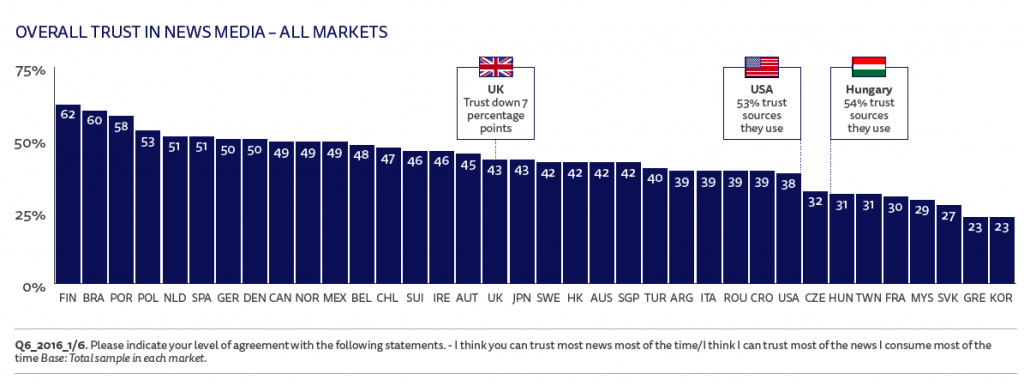

Trust in the media varies significantly across the 36 countries in the survey. The proportion that states they trust the news is highest in Finland (62%), but lowest in Greece and South Korea (23%).

In most countries, we find a strong connection between distrust in the media and perceived political bias. This is particularly true in countries with high levels of political polarisation. In the US, political polarisation means that respondents are more likely to trust news sources they regularly use (53%) than the news in general (38%). In the UK it seems that the fallout from the Brexit vote in June 2016, has led to a fall of 7% in overall trust in the media from 50% to 43%.

Levels of trust vary by political allegiance

In the US those on the political right are almost three times as likely to express distrust in the news in general compared with those on the left, whereas in the UK the pattern is reversed. This may reflect the difference between the media in each country; until recently, there was no US equivalent (when measured by circulation) to the highly partisan right-of-centre tabloid press that dominates UK newspapers.

In each country this has created gaps for new, partisan, digital-born websites to enter the market – with Breitbart achieving 7% weekly online reach amongst our US respondents and the Jeremy Corbyn supporting site, The Canary, scoring 2% weekly use in the UK.

Regional differences in paying for online news

Across all countries, only around one in ten (13%) pay for online news but there are big regional variations. Around a quarter pay for online news in Norway (26%) and around a fifth in Sweden (20%) compared with just 6% in Greece.

The report argues that this relates to higher disposable income as well as a culture of print subscription, which has been transferred to digital through bundling and free trials. But there may be another factor at work in some places. One positive side of polarisation and low trust in social media and the news media in general, has been a remarkable surge in the numbers prepared to pay for online news in the United States, growing from 9% to 16% of our online sample. Donations to news organisations have also tripled.

Most of the new subscriptions and other payments have come from those on the political left with almost a third saying they want to ‘help fund journalism’. Significant growth has come from the under-35s, a powerful corrective to the idea that younger groups are not prepared to pay for online media, especially for news.

There has been similar growth in paying for news online in another relatively polarised media environment, Australia. The number of Australians paying for news has increased from 10% in 2016 to 13% in 2017, with 25% of those paying saying their most important motivation is to ‘help fund journalism’. There are also relatively high levels of donations for news in Australia.

Increasing polarisation could benefit media organisations

Clearly the media business is experiencing challenging times, and the rise of polarisation, fake news and decreasing faith in social media are all causing concern. But there are signs that in some countries that same polarisation may be leading to a resurgent willingness – among some groups – to support the media organisations to which they feel closest. Political adversity may trigger an increased affinity with media organisations in some countries at least, which may be one way to help sustain the future of commercially-funded journalism.

Images: RISJ, DNR 2017

Ian Clark, Flickr CC licence

- 137Shares

- Facebook72

- Twitter7

- LinkedIn48

- E-mail1

- Buffer8

- WhatsApp1

Tags: audience trust, digital news, digital news report, New York Times, polarisation, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, trust, Washington Post