All dictatorships and authoritarian regimes censor the media in some way. The reason is obvious: a free press will usually investigate the actions of government officials, give space to the opposition and publish ideas contrary to official ideology. Yet even in the most difficult circumstances, journalists can evade the censors.

Varying degrees of authoritarianism lead to various degrees of censorship. From totalitarian North Korea, where all journalism is state controlled, to semi-functional democracies like Turkey, where an independent press exists, but journalists are often harassed or arrested if they criticise the government. In a research paper for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford (Evading the Censors: Critical Journalism in Authoritarian States), I investigated how journalists work in an environment of censorship. I talked to journalists and other people connected to the media in four countries: Singapore, Malaysia, Russia and Venezuela.

The countries have been selected because they are nominally all democracies, but they also have restrictions on those democracies.

They all have elected governments that are supported by large portions of the population. They all guarantee their citizens free speech and freedom of the press through their constitutions, but none of them have a free media in practice. Malaysia, Singapore, Russia and Venezuela all have both official and unofficial censorship. They are all rated low on media freedom indexes published by non-governmental organisations, such as Reporters Without Borders and Freedom House.

The censorship environment is different in the four countries, and journalists operate in different ways to circumvent them. But there are also common features in censorship evading in these countries. I have identified the following six methods journalists use to evade censorship.

1. Hide sensitive content

Journalists can hide sensitive content by presenting it in ways that disguise the true meaning for the censors, either by phrasing it in certain ways or putting it at the end of long articles. This method is used in Malaysia and Singapore. Although it was developed to perfection by journalists in the Soviet Union, it is not common in Russia today.

2. Ask critical questions at press conferences

One way for journalists to make information or criticism public, is to ask officials critical questions at press conferences. If the conference is broadcast live, the audiences will hear the questions. If it is not live, other journalists present may pick up on the theme and continue discussing the matter on blogs or in social media, where censorship may be lighter.

3. Publish sensitive material in media not associated with politics

Media that do not generally cover politics may sometimes get away with critical political reports. Interviewees mentioned the business media in Malaysia and lifestyle media in Russia as examples of outlets that can occasionally get away with criticism.

4. Operate media from abroad

This method is probably more used against totalitarian countries. In the countries I researched, the only example from my sources are Venezuelan journalists working from abroad and publishing online.

5. Share content with media outlets less likely to be censored

In some instances, if an editor does not want to publish a story, it can be sent to a media less likely to be censored or more willing to take risks. There are examples of this being done in Russia. According to a source in Venezuela, his newspaper will sometimes send stories to foreign media. The newspaper can then quote the foreign medium that ran the story.

6. Online media

The internet has opened up new possibilities for publishing both for journalists and the public in general. In both Malaysia and Singapore online journalists have more freedom than journalists in traditional media. In Venezuela people rely on social media for information they do not get through traditional media. Journalists sometimes use social media to publish news and comments their editors will not allow.

This is not an exhaustive list. Government censorship practices varies from one country to another, and journalists will have to tailor their methods to the environment they work in.

The limited outlets for critical journalism in the countries I have investigated does not serve as a substitute for full media freedom. The more outspoken media outlets usually have less reach than the rest of the media, so their impact is limited. If their audience becomes too big, the government might get anxious and crack down. But the fact that they exist, and provide critical journalism for those who look for it, provides some basis for diverse political discussion that the governments often try to avoid.

Given the opportunity, journalists find ways to publish sensitive material and they show creativity and ingenuity in their ways of making information available.

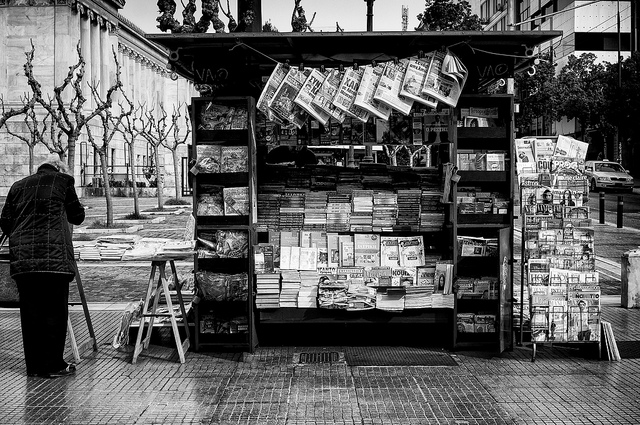

Photo: Flikr immediahk

Tags: Censorship, Journalism, Journalism research, Reporters without Borders, Social media