The attacks in Oslo last month once again brought up the issue of framing in the media. As it turns out, not only do media outlets set the agenda for discussion in society, they also dictate how people should feel about the subjects in question.

The attacks in Oslo last month once again brought up the issue of framing in the media. As it turns out, not only do media outlets set the agenda for discussion in society, they also dictate how people should feel about the subjects in question.

Ironically, anti-Islam extremist Anders Behring Breivik’s case emphasized the tendency of Western media to use prejudiced language when it comes to covering politically motivated violence committed by Muslims. Breivik’s attack was widely dubbed an “act of terror” in the mainstream media… that is, until Breivik himself was identified. As authors of the blog Foreign Policy Watch Matt Eckel and Jeb Koogler describe, the Western press responded by “largely avoiding the term ‘terrorist’ when speaking of the blond, blue-eyed, Christian attacker…” It seems that even those members of the media who did not clearly state that the attacker had connection to the Islamic extremists had secretly assumed this is exactly what the investigation would reveal.

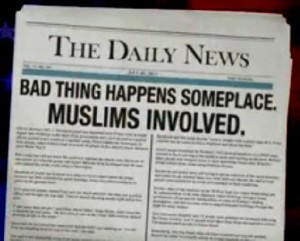

Hours before the Norwegian authorities released any official information about the executor of the horrendous act, many media outlets, including Fox News, MSNBC, the Wall Street Journal and other sizable news sources published assumption-based stories about the terrorists’ alleged connection to Al-Qaeda. American political satirist Stephan Colbert found the news behavior hilarious enough to feature on one of his shows, saying that the American media uncovered the terrorist long before the Norwegian government, describing Breivik’s action as “Muslish” and “Islam-esque”. He even offers a general headline for the news: “Bad thing happens someplace. Muslims involved.” Funny or not, the situation emphasized a legitimate frustration among Muslim communities with regard to the media’s coverage of the tragedy.

Identification of the actual criminal, however, seems to have brought little comfort to Muslims. From then on, as Eckle and Koogler observe, Breivik is called a “fundamentalist” or an “extremist”, but not a terrorist – a label reserved for Islamic assailants. Glenn Greenwald, an American columnist, writes that even when Breivik was identified to be an anti-Muslim Christian fundamentalist, the media used the word “terrorism” only to describe that he was “mimicking Al-Qaeda’s brutality and multiple attacks.”

One could argue, of course, that the wording doesn’t matter as long as the truth is released. Missouri School of Journalism researchers Kim and Cameron (2011) prove the opposite in a recent study. As part of an experiment, news stories about a fictitious company were prepared. The stories were framed in two manners – anger-inducing (e.g. focusing on company’s intentional wrongdoing, which results in a battery explosion) and sadness-inducing (e.g. focusing on the victims of battery explosion). The content of the two articles is identical except for the headline and the second paragraph. Both versions of the news were distributed randomly among participants, who were then asked to evaluate their feelings towards the company after having read the news.

The chief finding indicated that individual responses to a crisis are largely affected by the framing of the news. Those, who were exposed to anger-inducing news had more negative attitudes toward the subject than those who read the same news in a sadness-inducing frame. Though the research was focused on audience responses to the framing of corporate crises, the findings may also be applied to terror coverage.

The results of Kimberly Powell’s (2011) research on media coverage of terrorist attacks in the United States since 9/11 suggest that the act of terror is mostly used to describe “Muslims/Arabs/Islam working together in organized terrorist cells against a ‘Christian America,’ while domestic terrorism is cast as a minor threat that occurs in isolated incidents by troubled individuals.”

Such framing is most likely to induce anger not only among the non-Muslim Westerners, who naturally fear a loss of peace and well-being, but also among Muslims, who are forced to take a defensive position against the generalizing blame placed upon them by the Western media. Smoother coverage of domestic terror, on the other hand, puts two otherwise equal crimes on different levels of the brutality scale. It’s no wonder that misunderstanding and confrontation between Islam and the West continue to grow.

While wording in the media might explain Muslims’ frustration with the media and Christians’ fear of Islam to a degree, it remains unclear what is behind such skewed coverage in the first place. Apparently, it is time for media editors and journalism educators to think about introducing a new aspect of fair coverage – namely fair framing.

Hyo J. Kim, Glen T. Cameron (2011): Emotions Matter in Crisis: The Role of Anger and Sadness in the Publics‘ Response to Crisis News Framing and Corporate Crisis Response. Communication Research, XX(X), 1-30.

Kimberly A. Powell (2011): Framing Islam: An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of Terrorism since 9/11. Communication Studies, Issue 1, Vol. 62.

Tags: Andres Behring Breivik, extremism, Framing in the media, fundametalism, Glen Cameron, Glenn Greenwald, Hyo Kim, Islam, Jeb Koogler, Kimberly Powell, Matt Eckel, media coverage, Muslim, Oslo bombing, Terrorism